I am a voracious reader. Without any doubt, reading is one of my life’s greatest pleasures. But not everything I read can be considered pleasing since some of the books in my library are devoid of sweetness and light. On the contrary, they are depressing, shocking and troubling; they make me want to holler. Four such books, on a related topic, are Paddy’s Lament, Ireland 1846ᅳ1847 / Prelude to Hatred by Thomas Gallagher, Red Famine / Stalin’s War on Ukraine by Anne Applebaum, Mao’s Great Famine / The History of China’s Most Disastrous Catastrophe, 1958ᅳ1962 by Frank Dikötter and The Great North Korean Famine / Famine, Politics and Foreign Policy by Andrew S. Natsios.

Famine, in which lack of food wreaks havoc on an unsuspecting population, goes back a long time. The scope and magnitude can vary, as can the causes. Short- or long-term environmental factors such as cyclones, tsunamis, El Niño, volcanic eruptions, flooding and drought have been known to create famines. More often, they are man-made (a neo-sexist term for which I can find no better alternative). Famines have taken place in every continent, have brought down kingdoms, sparked peasant rebellions and migrations, and been interpreted as the gods’ need for human sacrifice. Depending on how you define “famine”—is it merely shortage of food or actual starvation?—Nigeria, South Sudan, Yemen, Somalia and North Korea are suffering from it now, in the fall of 2023.

Allow me to summarize what I learned in those four books.

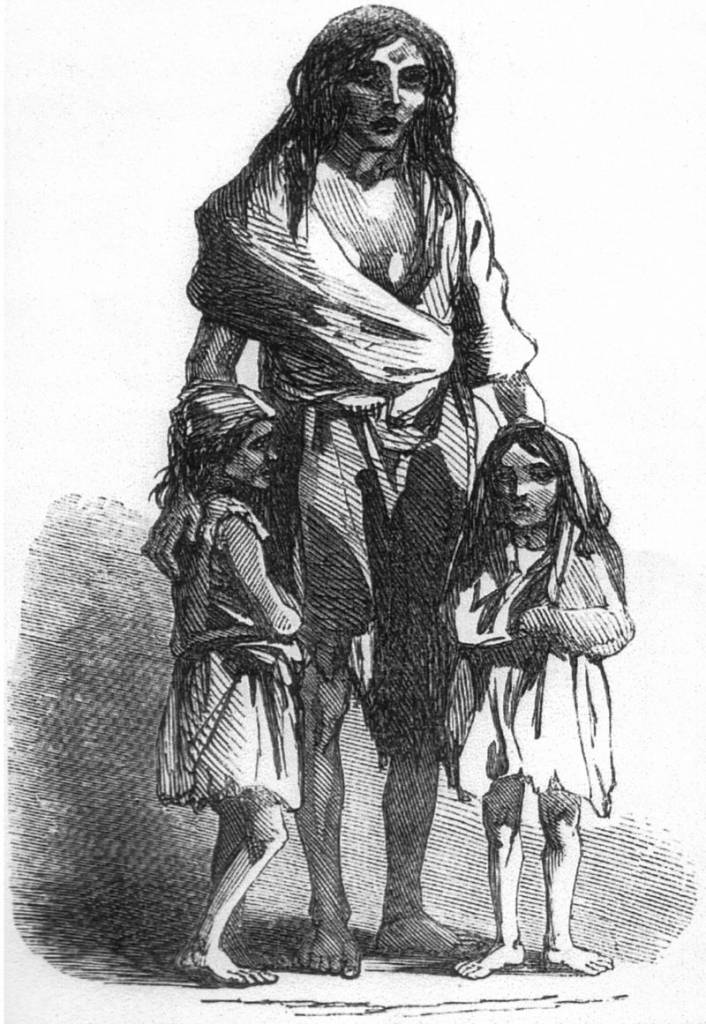

Gallagher (1918ᅳ1992) is the son of an Irishman who immigrated to the United States, so we might expect him to be biased, but he told it straight. And that was plenty bad. The proximate cause of the Great Famine (or Gorta Mór) was potato blight, as the vast majority of Ireland’s rural people relied on this one vegetable for sustenance. But they had been eating almost nothing but potatoes for years because the Whig administration in London refused to bar the export of food from Ireland to England and the rest of well-fed Europe. Even when heart-breaking tales were filtering back and it was obvious that a major disaster was happening, British leaders held tight to their laissez-faire economic doctrines. Roughly 1 million people died, and twice that number fled the country.

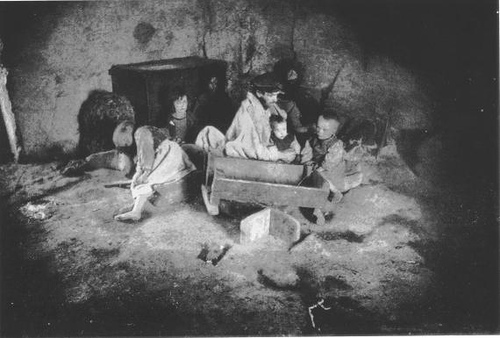

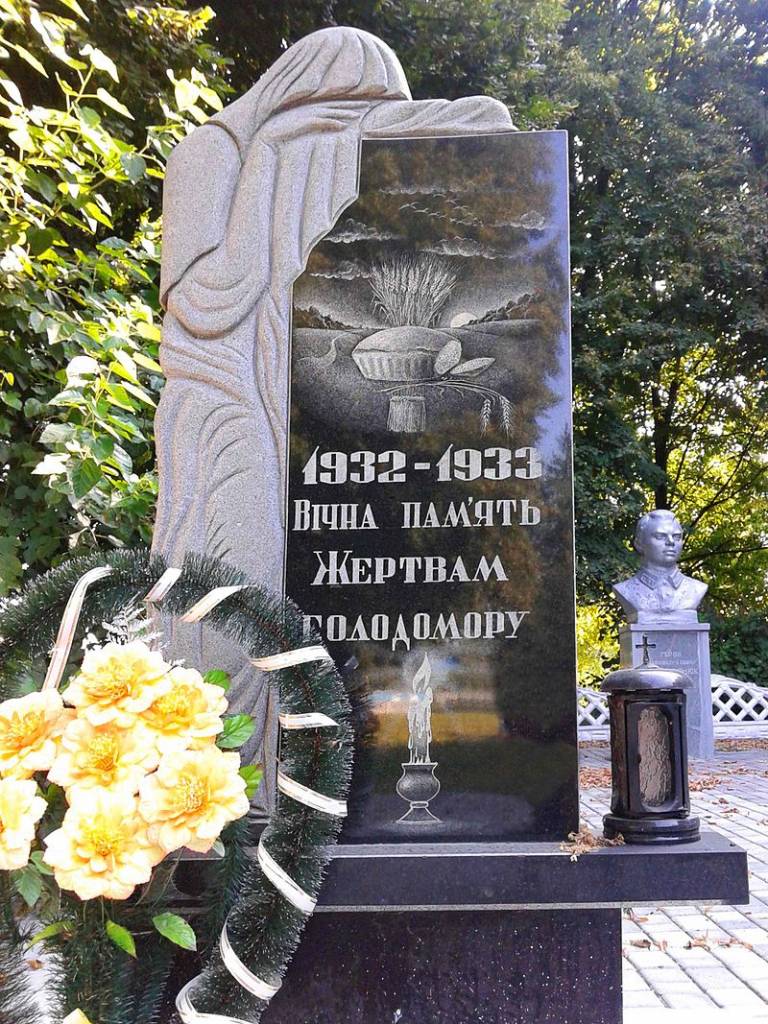

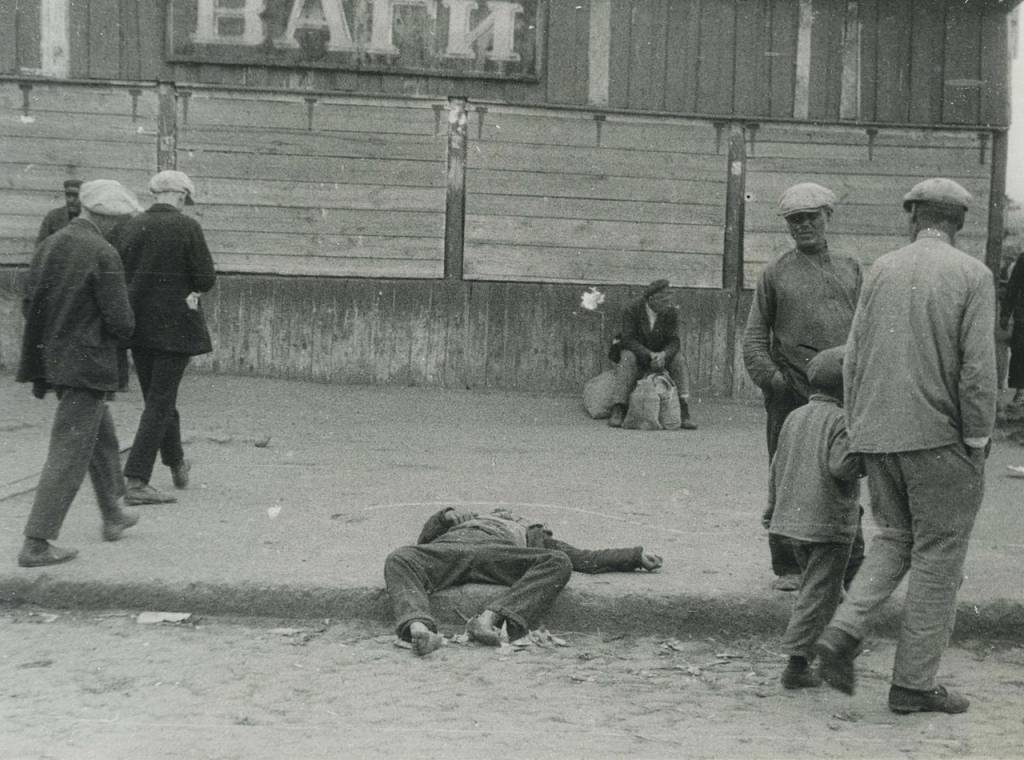

The Holodomor, which killed between 3.5 and 5 million Ukrainians in the early 1930s, was in fact part of a wider Soviet famine that affected the major grain-producing areas of the country. And Ukraine was the breadbasket of the USSR. Some scholars—and Applebaum seems to be one of them—conclude that Joseph Stalin cruelly planned and exacerbated the famine to stifle any notion of Ukrainian independence. Stalin’s large-scale agricultural collectivization policy did not work, as the amount of harvested grain fell. There were ghastly scenes in Kyiv, Kharkiv and other major cities, with corpses in the streets, but things were even worse in the hinterland. The effect of the famine in Ukraine continues to this day.

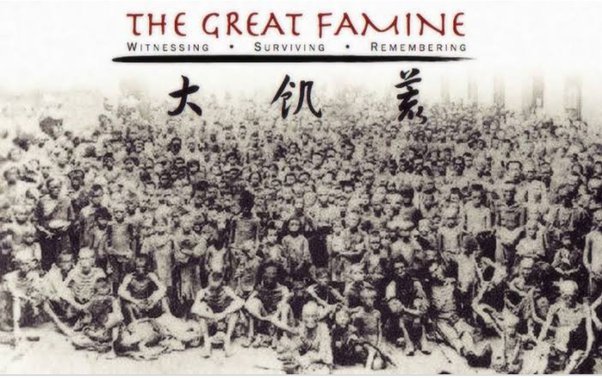

Dikötter’s book is the second in a trilogy on modern Chinese history, and I read each one. Here, he informs us about the so-called Great Leap Forward in which Mao Zedong’s infatuation with gigantic projects caused a famine that dwarfs all the others. The numbers are staggering: at least 45 million Chinese people died of starvation or the effects of inadequate food. He thought that, by force of will, China could join the world’s industrial superpowers almost overnight and show what the red flag of communism could achieve. Just as Stalin’s associates in the Kremlin were afraid to tell him the truth, Mao had plenty of politically level-headed comrades-in-arms but they dared not contradict him; to do so was to risk a quick death. How a huge (6 × 4.6 meters) portrait of this monster continues to adorn the main façade of Tiananmen Square, I do not know.

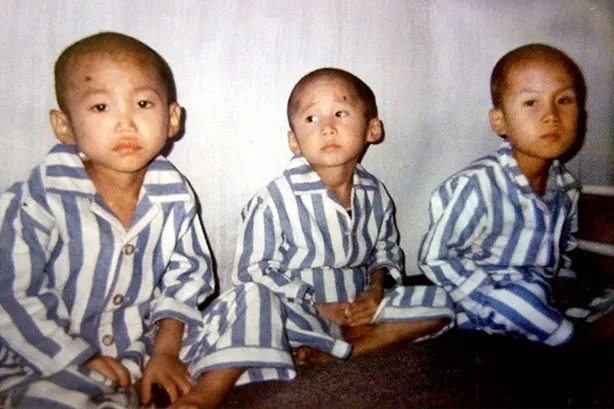

As in Ireland, as in Ukraine and as in China, the people of North Korea endured a wholly unnecessary nightmare of malnutrition, starvation and even cannibalism. Natsios (administrator of the U.S. Agency for International Development when he wrote the book) exposed the horror that unfolded behind the DPRK’s borders between 1994 and 1998. As many as 3.5 million people died prematurely despite Kim Il-Sung’s promise that every North Korean would be provided with “beef soup and white rice” three times a day. He, like Stalin and Mao, was a bloviating, ill-educated commie. The “Arduous March,” as they call it north of the border, was not ameliorated until his son, Kim Jong-Il, reluctantly allowed other countries to donate massive amounts of food. Note, however, that the North Korean state refused to let donor representatives supervise the distribution of their aid; it went to the elites and military first and foremost. And to say that the famine ended in 1998 is deceptive since people outside of Pyongyang even now can barely survive.

Ireland…

Ireland…

Ukraine…

Ukraine…

China…

China…

North Korea…

North Korea…

Add Comment