There are some things we know for certain about Anna Wallis Suh. She was born in 1900 in Lawrence County, Arkansas, the youngest of six children in a farming family. Orphaned in her early teens, she moved to Oklahoma to live with one of her sisters. Suh taught Sunday school while working her way through Southeastern State Teachers College in Durant and Scarritt College for Christian Workers in Nashville, Tennessee, from which she earned a BA.

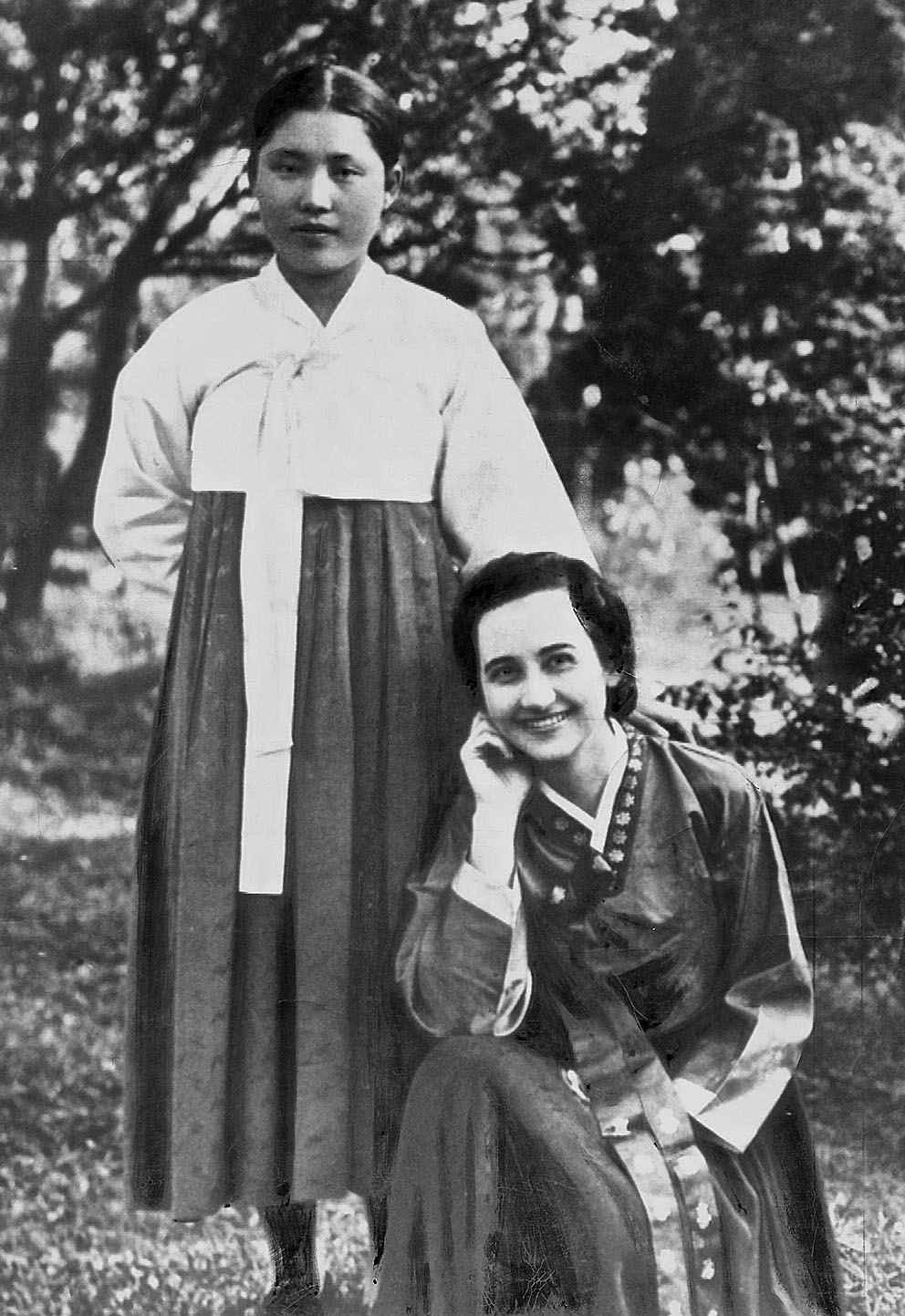

Thirty years old upon graduation, she may have been eager to escape small-town life. Suh was hired by the Southern Methodist Episcopal Mission and sent to Seoul, Korea. She worked there for eight years, operating out of the still-extant Jeongdong First Methodist Church. But Japanese colonial authorities were clamping down on the activities (indeed, the presence) of foreigners in Korea. In 1938, she went to China (also controlled by the Japanese) and got a job at the Shanghai American School. From then on, details of her life become increasingly murky.

Suh met a Korean man named Suh Kyu-cheol in Shanghai and soon married him, although, according to the sexist laws then in force, it meant losing her American citizenship. Interned by the Japanese in 1943, the husband-and-wife team resumed work at SAS at the conclusion of World War II. But things were getting hot in China with Mao Zedong’s Communist forces about to push the Nationalist government out and over to Taiwan. So the Suhs high-tailed it back to no-less-turbulent Korea in 1946, at which time she joined the faculty of the U.S. Legation School. As a teacher of diplomats’ kids, she either let slip some of her political views or the activities of her husband caused alarm to her employers. At any rate, Suh was fired in 1949.

The next summer, as you know, the Korean War began. Most residents of Seoul panicked and fled south. Suh and her husband did not, however. Kim Il-sung’s soldiers spread the message: “The People’s Republic is now in control.” They did more than make brash statements—they rounded up, tortured and killed perceived opponents. The Suhs, with solid left-wing if not Communist credentials, were safe. They were among the civilians (including 50 or so members of the National Assembly) who on July 10 pledged their allegiance to the man who would eventually call himself the “Great Leader.”

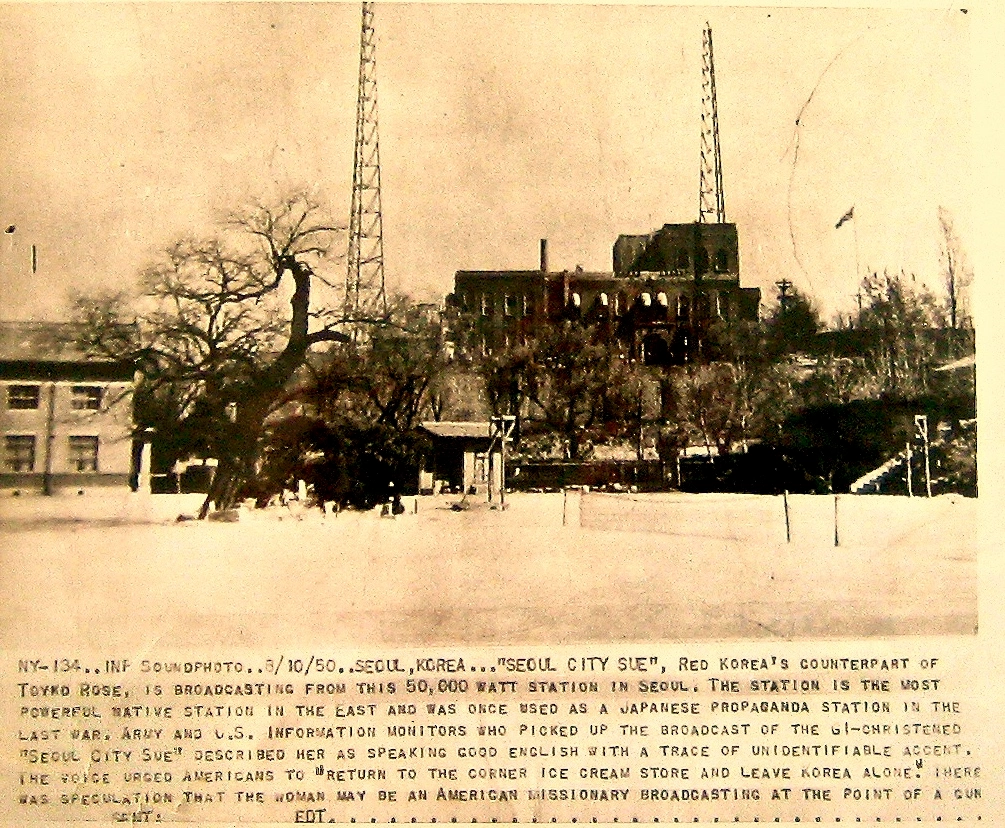

What happened next was a key event in Suh’s biography. It’s hard to say whether she was compelled or voluntarily became an announcer at the HLKA studio of the Korean Broadcasting System in Yongsan. At this station, formerly operated by the Japanese, Suh had a nightly program in which she played music and bemoaned American and United Nations resistance to North Korea’s “liberation” of the South. In a bland, monotone voice (she was obviously not trained to be a radio announcer), she praised Joseph Stalin, vastly overstated the number of dead American soldiers and urged those still alive to quit and “go home to the corner drug store.” She became more provocative as time went on, reading the names of Allied soldiers who had been captured or killed and identifying American ships docking at, or departing from, Busan.

No longer a U.S. citizen, Suh could not have been charged with treason if apprehended by the American army. But this was wartime, and I think it highly probable that she would have been turned over to the South Koreans, given a hasty trial and sent into eternity. What she was doing echoed the actions of Mildred Elizabeth Gillars, better known as “Axis Sally.” This Ohio native broadcast Nazi propaganda between 1942 and 1945 from a Berlin radio station and paid the price with 12 years in the Federal Reformatory for Women in Alderson, West Virginia.

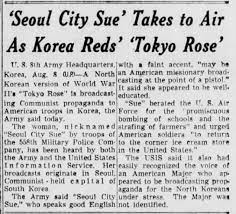

Suh’s GI listeners gave her a nickname, too: “Seoul City Sue.” It was taken from a 1946 song by Zeke Manners entitled “Sioux City Sue.” Her identity was soon revealed, partly with the help of one of her sisters back in Oklahoma. She was loyal and quick to emphasize that Suh could not be a turncoat; she must have been coerced, perhaps even at the point of a gun. After all, why would a Christian missionary woman join up with a bunch of atheistic Communists? General Douglas MacArthur didn’t buy that. He called for her capture, and it surely would have happened soon after American soldiers landed at Incheon and re-took Seoul in late September.

By then, however, Suh and her husband had joined the North Korean army’s headlong retreat. First they reached Pyongyang, capital of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. Not for long, though! Mac’s boys did not stop at the 38th parallel. They had the Communists on the run, such that Kim was asking Mao about the possibility of setting up a government-in-exile in China. That was obviated by the entrance of Chinese forces on October 19. Now the Americans, South Koreans and others were retreating. The Suhs, who had probably gone all the way up to the Yalu River, then headed back to Pyongyang. She did sporadic broadcasts, was put in charge of English-language publications for the Korean Central News Agency and worked at a political indoctrination camp (teaching classes about Marxism, among other things) until the armistice was signed on July 27, 1953.

The remainder of her life is even sketchier. In fact, the only word we have comes from a somewhat unreliable source—Charles Robert Jenkins. This 24-year-old Army sergeant drank several beers to get his courage up and then crossed the DMZ one night in January 1965. As a result of that foolish act, Jenkins spent almost four decades in North Korea. In his 2008 memoir, The Reluctant Communist, he stated that he had encountered Suh in the foreigners-only section of Pyongyang’s No. 2 Department Store in mid-1965. Their meeting was awkward and brief. Jenkins also claimed to have seen a photo of Suh in a propaganda pamphlet dated 1962. He said he was informed by his ever-present minders that Suh, no longer of value to the North Koreans, was accused of being a South Korean agent and shot in 1969. Jenkins’ assertion is bolstered to some extent by stories from defectors to the South in the early 1970s who said the same thing.

A Korean War footnote, Anna Wallis Suh has been forgotten other than occasional references to her in the M*A*S*H television series (1972-1983). The actual fate of Suh, and of her husband, is a mystery that cannot be answered unless North Korean files see the light of day. And that will happen only when the revolution comes.

Young Anna Wallis…

Anna in 1928 as a college student…

Radio station in the Yongsan district of Seoul, where Suh’s broadcasts took place…

Newspaper article from that time….

Charles Robert Jenkins…

1 Comment

I did enjoy reading this story. It is interesting to read what so many of the civilians braving did in war times. Thanks for sharing.

All good here. And how about you? Have a Happy Thanksgiving and Merry Christmas.

Add Comment