I have written elsewhere about my experience as a reader of Tom Swift books in 3rd and 4th grades at Edwin J. Kiest Elementary School in Dallas. Since my family moved three miles northwest in the summer of 1963, I was no longer a Kiest Indian but a Hexter Hawk. That precluded me from taking part in a unique intraschool drama.

It bears mentioning that we were in the “accelerated class” at Kiest. Our curriculum must have been a bit harder and the teachers more demanding than in other classes. I can tell you for sure that we had some smart kids and strong personalities in 3B and 4B, and that was presumably the case in later years.

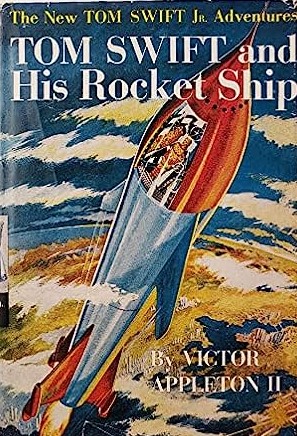

I avidly read the Tom Swift adventure stories ghostwritten by “Victor Appleton II” for the Stratemeyer Syndicate and published by Grosset & Dunlap. Classmates who did the same included David Twedell, Barry Payne, Jarrett “Reggie” Hervey, Rodney Elkins, David Posey, Tony Sandow, Jimmy Allen, Jeff Irion and Jeff Seacrest. There might have been others. The Kiest library had no Tom Swift books because they ostensibly lacked literary value. This was the opinion of the librarian, Mrs. Smith. When she saw that some of the 5B boys were reading Tom Swift books in her library—the lady seemed to think of it as her library—she was not reticent in calling them abominable. I hesitate to say she placed a malediction on Tom Swift, but it was close.

Twedell, Payne and Hervey led a group that questioned the wisdom and fairness of her policy. The original plan was on a fairly small scale: a debate among students in the 5B classroom. But Mrs. Smith somehow got wind of this and the thing grew to involve school faculty and administration. The principal agreed to hold a debate in which the question would be determined: Was Tom Swift any good, and did these tomes merit inclusion on the shelves of the Kiest library?

First, however, Payne wrote a letter to the director of the Stratemeyer Syndicate. He got back a quick reply stating several reasons why the Tom Swift books had merit. That clever ploy may have made all the difference.

The debate occurred one day in late 1963 or early 1964. Twedell, clutching the Stratemeyer letter in his hand, did most of the speaking in favor, while Mrs. Smith took the opposing view. In a manner that would have pleased Tom Swift and his loyal sidekick Bud Barclay, he advocated with some passion that these science-fiction adventure tales (for example, Tom Swift and His Triphibian Atomicar, Tom Swift and His Megascope Space Prober, Tom Swift and the Asteroid Pirates, Tom Swift and His Repelatron Skyway, and Tom Swift and His Aquatomic Tracker) actually made good reading for intelligent boys such as them.

The judges were the Kiest principal and two teachers—Mrs. Dondelinger and Mrs. Carmichael. Mrs. Smith, of course, led the opposition. Twedell (who, like Elkins, would go on to a successful career as an attorney) had some closing arguments that would have made Perry Mason proud. He suggested that since books such as The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Charlotte’s Web, The Chronicles of Narnia and The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes were in the library, why not Tom Swift? It might have been far-fetched and formulaic, but it was not fluff. I hope Twedell added that the most important thing by far is that these young men in Kiest’s 5B class were reading. Reading, as I have stated many times before, is of profound importance; get a kid in the reading habit and you will do him or her a big favor. Children who read come to love learning for its own sake, and they develop higher-order thinking skills. The doorway to imagination and discovery, reading may be the most important marker for scholastic success.

At any rate, both sides made a presentation and rebuttal. The judges met, conferred privately and came out in support of our heroes—Twedell, Payne, Hervey, Elkins, Posey, Sandow, Allen, Irion and Seacrest. The losing side did not take defeat gracefully; Mrs. Smith argued with the judges afterward, to no avail. The ruling had been made, and she was told to order a series of Tom Swift books without delay.

It’s a shame that no photographs were taken of this extraordinary event. A feature writer from the Dallas Morning News or Times Herald should have been dispatched to 2611 Healey Drive to witness it and do an article. Why wasn’t a Channel 8 camera crew on hand to bring it to viewers across the city?

You may note that this was an all-male endeavor. The girls of 3B, 4B and 5B, pretty darn bright themselves, had their own favorite set of books featuring the teenage Nancy Drew. Part of the Stratemeyer Syndicate as well, they included such titles as The Mystery of the Fire Dragon, The Clue of the Dancing Puppet, The Moonstone Castle Mystery and The Phantom of Pine Hill. Fifth grade—that was about the time boys and girls really started to notice each other. It is a fair guess that the female students at Kiest in the 1963-64 school year admired what Twedell et al. had achieved.

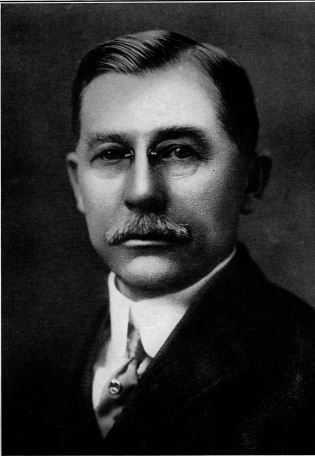

I also think it likely that Edwin John Kiest (1861-1941; newspaper publisher, twice president of the State Fair of Texas, financial supporter of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra, director of the Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Crippled Children, and recipient of honorary degrees from SMU and Texas A&M, among other things) would have smiled at these proceedings and said, “Job well done.”

My old school…

Go, Indians…

Namesake of our east Dallas elementary school…

Add Comment