Due to congestive heart failure brought on by pneumonia, James Nathaniel Brown went the way of all flesh on May 18. His 87-year life is a mixture of appealing and appalling. I will address the former before moving on to the latter.

A native of the Sea Islands off the coast of Georgia, his family went north to Manhasset, New York when he was eight. At Syracuse University between 1953 and 1956, the 6′ 2″, 230-pound Brown played football, basketball and lacrosse, and was a decathlete on the track team. The focus here, of course, is football. In his senior year, the Orangemen went 7-2 with a one-point loss to TCU in the Cotton Bowl. He was a consensus all-American, but there may have been some doubt about him because Syracuse was an Eastern college, and football in the East was fairly weak; the Orangemen played such teams as Holy Cross, Colgate and Fordham, which are not to be confused with Ohio State, Southern Cal and Oklahoma.

If pro scouts had performed their due diligence, however, it would have been obvious that Brown—an unprecedented combination of size, speed and power—was the best player available in 1957. In the first round of the NFL draft, the Green Bay Packers (twice), Los Angeles Rams, San Francisco 49ers and Pittsburgh Steelers selected other guys, leaving Brown for the Cleveland Browns.

Thrice the NFL’s most valuable player, he was a key factor in the Browns winning the 1964 league championship (27-0 over the Baltimore Colts); Cleveland lost to the Detroit Lions 59-14 in the 1957 title game and the Packers 23-12 in 1965, the last before the Super Bowl era. Brown gained 12,312 yards rushing in his pro career for a splendid 5.2-yard average. He led the league in rushing every season but one—1962, when he had an injured wrist. He caught 262 passes, scored 126 touchdowns and played in the Pro Bowl every year. ESPN has named Brown the game’s greatest player at both the college (Best ever in college? He did not score a single touchdown as a sophomore.) and pro levels.

In the summer of 1966, he shocked the sports world by announcing his retirement after just nine seasons. He called Browns owner Art Modell from London, where he was filming The Dirty Dozen and said he was through with football. Fancying himself a thespian, he would appear in numerous films and TV shows over the decades to come. Was he any good? One of his co-stars in The Dirty Dozen, Lee Marvin, put it diplomatically: “Well, Brown’s a better actor than Laurence Olivier would be as a member of the Cleveland Browns.”

He may have thought the Browns would miss him, but Leroy Kelly (his backup the previous two seasons) proved he could play rather well. He gained 3,585 yards and scored 37 TDs from 1966 to 1968.

I credit Brown for seeking to promote black economic success and for his work as a civil rights activist. His early youth was spent in the Deep South, so he knew discrimination. He organized the 1967 Cleveland Summit in which a dozen prominent black athletes—no White ones—met with Muhammad Ali to discuss and finally support his refusal to be inducted into the military. In 1992, Brown had the gravitas needed to facilitate a truce between the two main gangs in Los Angeles; it didn’t last long, of course.

Let’s go back to football for a moment. Brown, it must be said, was a prima donna. I have never heard of a fullback who refused to block, but Brown just would not do it. He drove his coach, Paul Brown, crazy for this reason. “As a pure runner, he stood alone,” Brown later said. “Still, I could never excuse his lack of effort in blocking—in some instances so poor that pass rushers went right past him. Other times, he failed to help other running backs when he was the lead blocker.”

It was an open secret around the NFL that Brown, the toughest of tough-guy runners, considered blocking to be beneath him. He all but admitted it with a faulty analogy: “Do you ask Liberace to carry his piano?”

Cleveland quarterbacks Milt Plum and Frank Ryan must have had a hard time setting up in the pocket, knowing Brown was doing his matador act. But there was one player in particular for whom Brown went soft as a blocker: Bobby Mitchell. A seventh-round pick out of Illinois in 1958, he had a huge impact right off the bat. Consider that Mitchell gained 500 yards on 66 carries over his first five games. Brown at that point had just 279 yards on 80 carries. Brown was concerned that the rookie was overshadowing him—as indeed he was—and virtually instructed his coach to bench him or move him to another position.

He employed similar dirty tactics in 1959. Things came to a head in the eighth game of the season, a 31-17 defeat of the Washington Redskins. Brown gained a pedestrian 40 yards on 16 carries, whereas Mitchell had 232 yards on 14 carries, despite his fullback refusing to block opposing defenders! He did all that in three quarters and so was about to break Brown’s NFL record of 237 yards from scrimmage in a single game. At Brown’s insistence, Mitchell did not carry once in the fourth quarter.

Furthermore, Brown—with a 40-pound weight advantage—repeatedly threatened to whip Mitchell’s butt. Tell me, dear reader, if that sounds like the behavior of the greatest football player of all time.

(Traded to Washington before the 1962 season, Mitchell continued his scintillating ways. When he retired in 1969, his 14,078 combined net yards were the second-highest in NFL history. Thomas Boswell of the Washington Post wrote an appreciation of Mitchell after his death on April 5, 2020: “As a four-way threat—running the ball from the backfield, catching passes as a wide receiver and returning kickoffs and punts—Mitchell is unique. No other player has been among the very best in all four areas. Mitchell is a group photo of one…. Who is the only NFL player with more than 500 career rushes and 500 receptions to average more than five yards per carry [5.3] and more than 15 yards per catch [15.3]? Bobby Mitchell.”)

I do not roast Brown because he was a mediocre actor or a half-hearted blocker, or because he was instrumental in getting Paul Brown fired before the 1963 season, although each of those points is indisputably true. No, my main beef is that he had a long history of violence away from the gridiron. To wit:

In 1965, an 18-year-old woman accused Brown of plying her with alcohol and then forcing her to have conjugal relations. Charged with assault and battery, he was acquitted by a jury in a 10-day trial.

In 1968, he faced a charge of assault with intent to murder after allegedly throwing a 22-year-old woman from a balcony. When she refused to name Brown as the perpetrator, the charge was dropped.

The next year, Brown was acquitted on charges of beating up a man after a traffic accident.

In 1971, charges that Brown beat two women and threw them down a flight of stairs were dropped when they failed to testify at his trial.

In 1978, Brown assaulted a fellow golfer in an argument over the placement of a golf ball. For this, he was fined $500 and jailed for one day.

In 1985, Brown was charged with rape, sexual battery and assault. When the 33-year-old victim gave inconsistent testimony, however, the charges were dropped.

His next run-in with the law came in 1986 when he was arrested for allegedly beating his girlfriend for allegedly flirting. That, too, came to naught when the 21-year-old woman said she did not want to prosecute.

In 1999, Brown was convicted of smashing the window of his 25-year-old wife’s car with a shovel. She claimed he threatened to kill her, but he was acquitted of making terroristic threats. The judge sentenced him to three years’ probation, revoked his driver’s license for a year and ordered him to attend counseling for domestic abusers. Brown refused—saying that for him to undergo such counseling would be “undignified”—and spent three nights in the pokey.

That is one heck of a rap sheet, and it was mentioned in few of the encomiums about Jim Brown over the last two weeks.

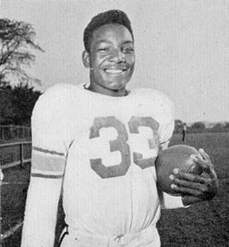

Brown as a high school football player, 1953…

Brown (number 30) with Syracuse basketball teammates, 1954 or 1955…

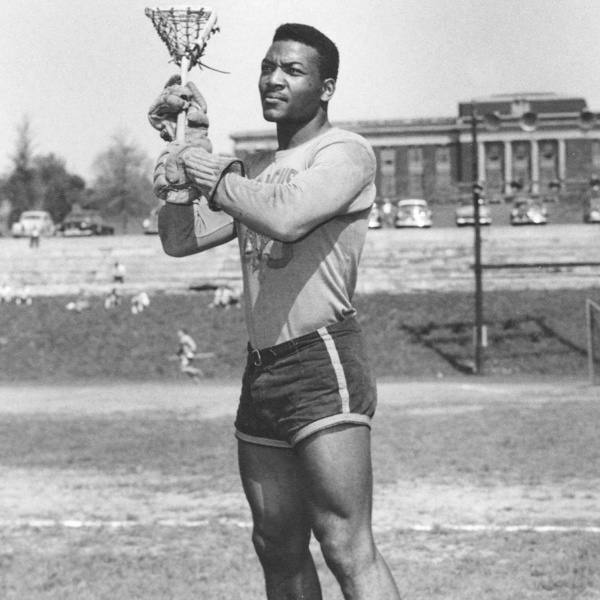

Brown with the Syracuse Orangemen….

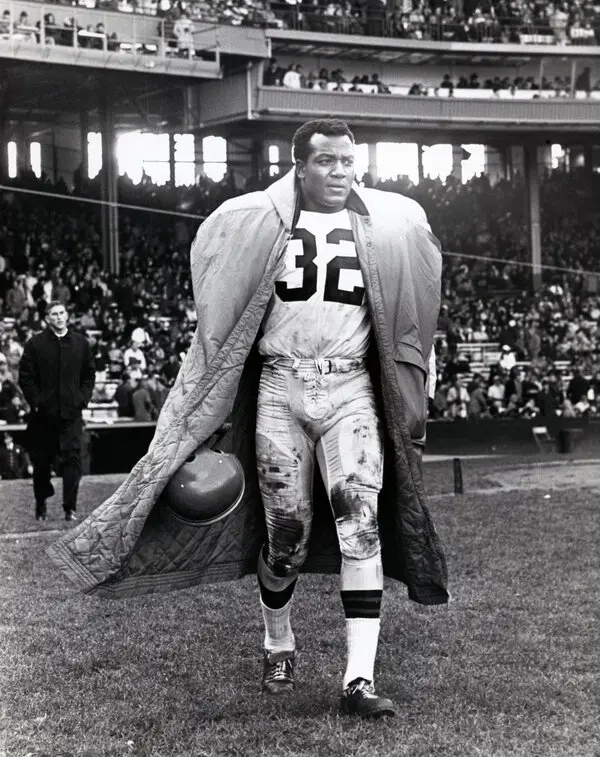

Brown of the Browns…

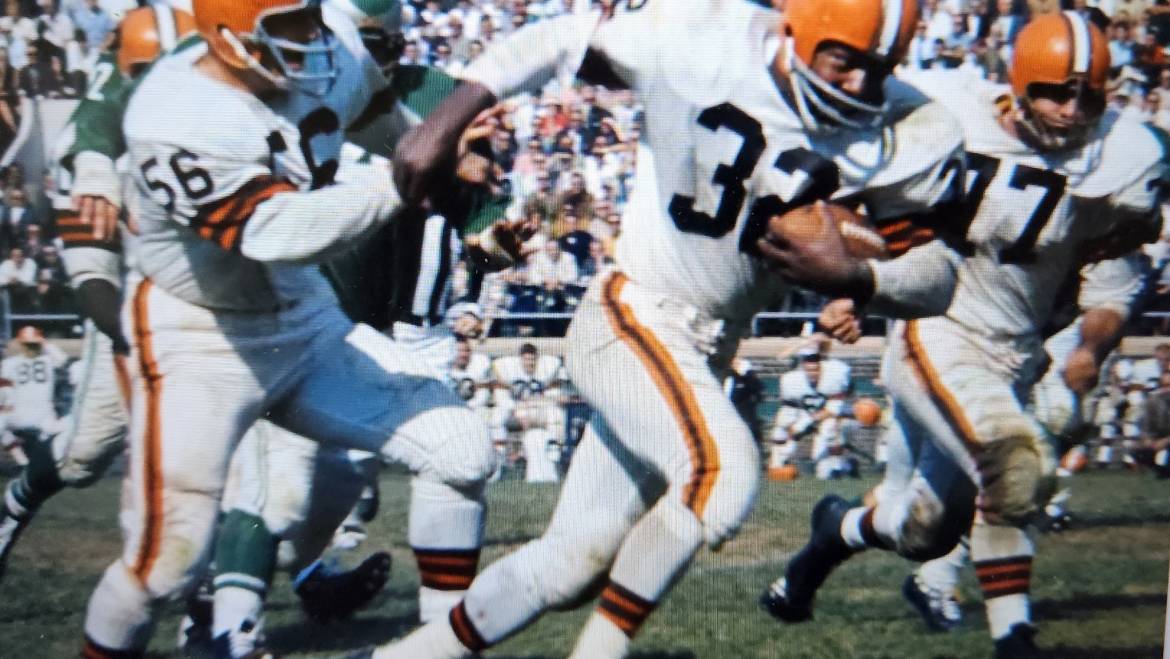

Bob Lilly of the Dallas Cowboys tries to bring down number 32…

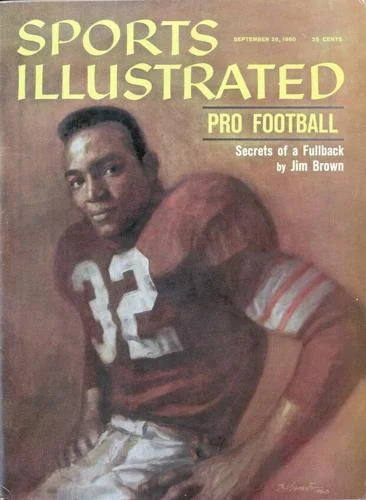

On the cover of Sports Illustrated…

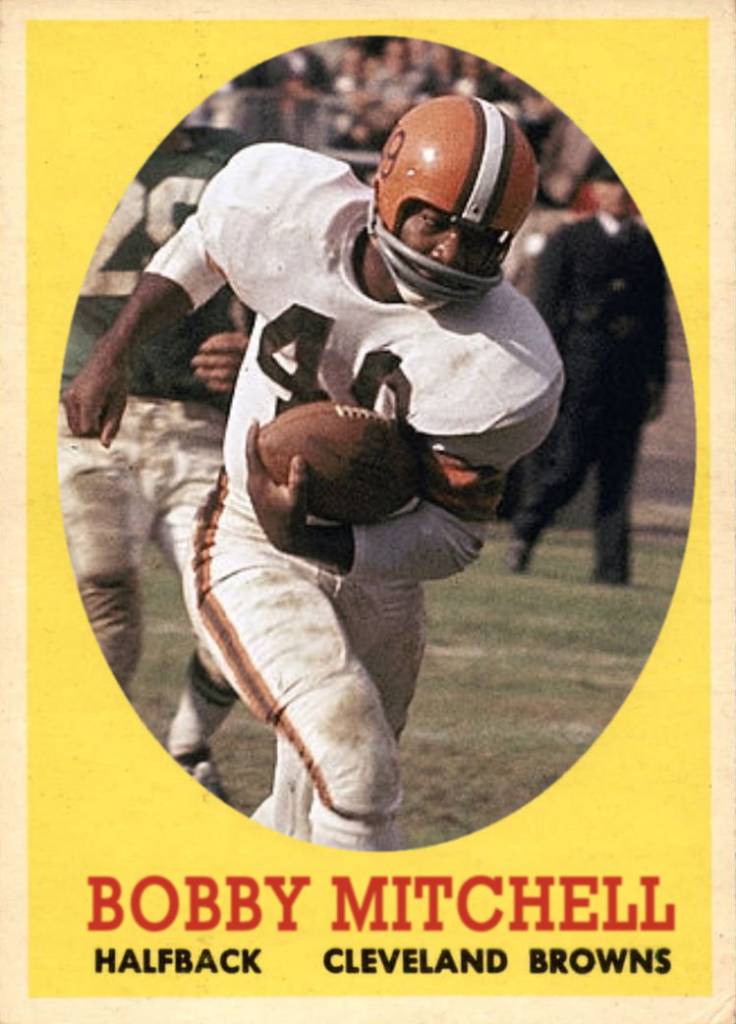

Bobby Mitchell, for whom Brown refused to block…

The Cleveland Summit, 1967…

2 Comments

Van Morrison “Who Was That Masked Man?”

“No matter what they tell you

There’s good and evil in everyone”

We want our heroes to be non-Homeric non-Greek-tragic, i.e., not flawed

but as the ancient Greeks knew, that is just not so.

Add Comment