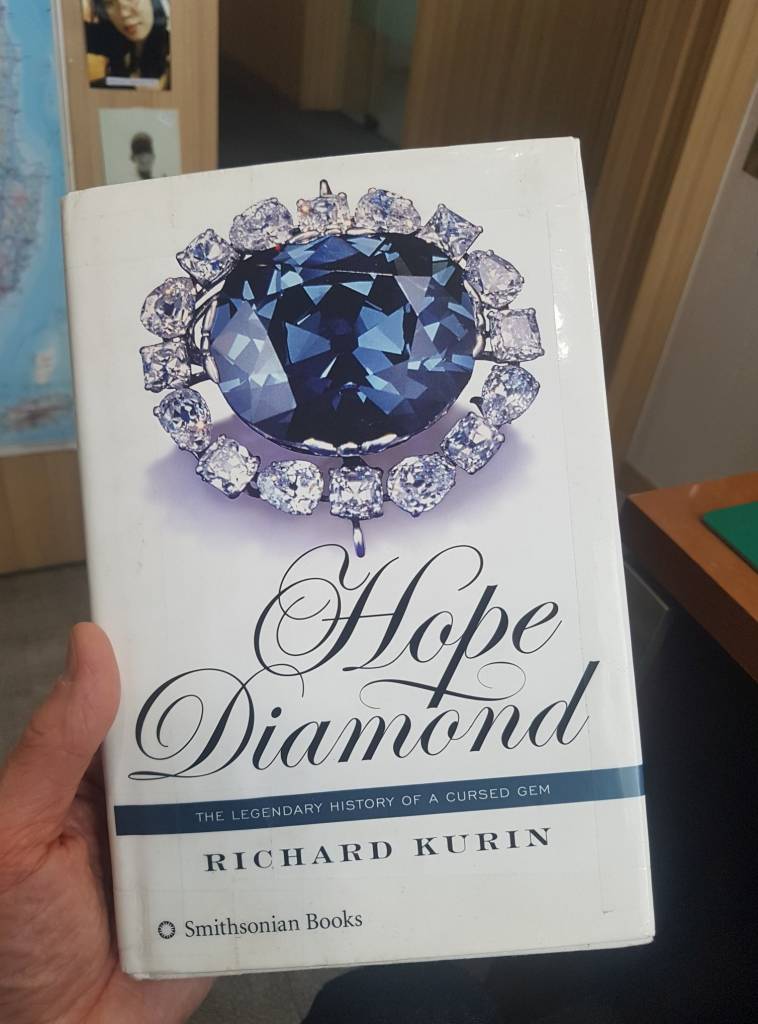

I can understand why the Hope Diamond is such a popular exhibit at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History. The magnificent 45.52-carat blue diamond—allegedly the subject of a Hindu curse that influenced the French Revolution and has resulted in suicides, mob violence, divorces, financial ruin and other disasters—has been seen by more than 200 million visitors since its purchase in 1958 from New York jeweler Harry Winston.

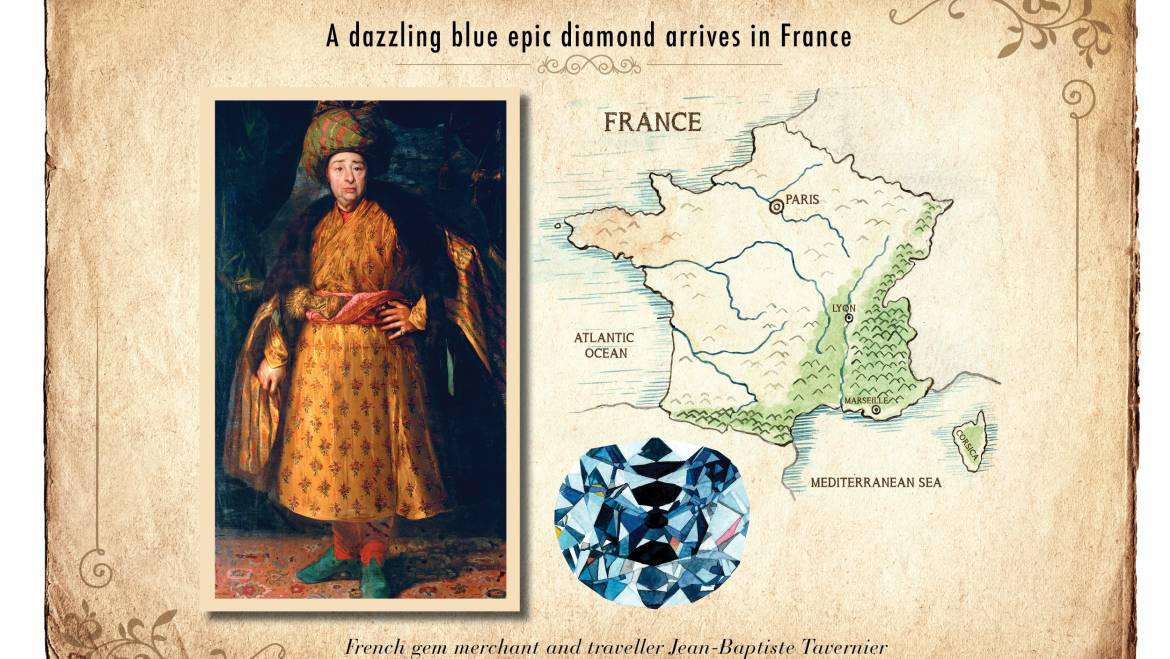

French business man, traveler and cultural anthropologist Jean-Baptiste Tavernier obtained the rock in the mid-1600s from India’s Golconda Mines legally, or did he? We’ll never know for sure. He was rumored to have snatched it from the eye of a Hindu goddess in Kali Temple, subsequently selling it to King Louis XIV. The 112.30-carat Tavernier Violet was cut and renamed the French Blue and finally the Hope Diamond. Other owners would include, with varying degrees of certainty, the Duke of Brunswick, his daughter Caroline, London diamond merchant Daniel Eliason, King George IV, Henry Philip Hope, his nephew Henry Thomas Hope, the dissolute Francis Pelham-Clinton-Hope, New York jeweler Joseph Frankel, Turkish Sultan Abdul Hamid II, Paris jeweler Simon Rosenau, the Cartier Brothers, and Ned and Evalyn Walsh McLean. Winston bought it from their estate in 1949.

Leonard Carmichael (secretary of the Smithsonian), Richard Howland (head curator of the Smithsonian’s Museum of History and Technology), Dr. George Switzer (the Smithsonian’s curator of mineralogy) and other higher-ups were in agreement when France’s Ministry of Culture made an appeal for the Hope Diamond to be loaned for a one-month exhibit at the Louvre entitled “Ten Centuries of French Jewels” in 1962. That is, they wanted to issue a polite “no.” In just four years, the Hope Diamond had come to be regarded at the Smithsonian as a national treasure, the centerpiece of a growing set of splendid jewelry that rivaled or possibly exceeded that of the French or British.

Pierre Verlet, chief conservator of the Louvre, argued that since the Hope Diamond had made up the larger part of the French Blue it ought to be featured in that showing. He persisted, asking that President John F. Kennedy be consulted. Before the men at the Smithsonian could categorically reject that idea, French Minister of Culture Andre Malraux got in on the act. He had met First Lady Jackie Kennedy in Paris in May 1961 and was entranced by the way she spoke French, appreciated French culture and history, and so on. Malraux started lobbying her, stating why it made perfect sense for the Hope Diamond to be presented alongside the Cote de Bretagne, the ruby that was central to the insignia of the 600-year-old Order of the Golden Fleece. Mrs. Kennedy—it is unclear to what extent she discussed it with her husband—was all in favor. This would be one of the main foci of the Ten Centuries exhibition. The Smithsonian’s Board of Regents met and reluctantly concluded that a refusal would be impossible. That did not prevent them from complaining, with the utmost discretion, that she had no right to advocate a loan of the Hope Diamond to France. It did not fall within her remit as First Lady.

A newspaper article entitled “Jewels for Jackie” snarkily commented that the Smithsonian’s gem collection might serve as a kind of repository from which the president’s wife could decide how to adorn herself on formal occasions: “One of these days, Jacqueline Kennedy may pick up the telephone and call the custodian of national jewels. ‘Send over the Napoleon necklace and the sapphire brooch,’ she could say, ‘and…no, not the Hope Diamond this time. I wore it last week at the French Embassy.’” The press, despite being in thrall to JFK and his sophisticated wife, nonetheless issued guarded criticisms about the “royal presidency.”

At any rate, Malraux was the guest of honor at a glamorous White House state dinner in May 1962, at which time Mrs. Kennedy gave him the news. Switzer took the Hope Diamond (insured for $1 million) to Paris and handed it over to Verlet. The Louvre exhibit was a big success, giving the USA much-wanted cachet in the eyes of the French and other Europeans. The Hope Diamond was returned, no worse for wear, to its home in Washington, D.C. (It would also be loaned to De Beers for the Rand Easter Show in South Africa in 1965 and to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1982, as a way of honoring Harry Winston who had died four years earlier.)

One reason the Americans had acceded to the 1962 French request was the suggestion that a reciprocal loan might be arranged. And so it was, due to the adept maneuvering of Mrs. Kennedy. The objet d’art in question is the Mona Lisa, the most famous painting in the world. The half-length portrait of a lady with an enigmatic smile was done by Leonardo da Vinci between 1503 and 1506. It has been a French possession for more than four centuries; the Mona Lisa once hung in the bathroom of King Francois I and in Napoleon’s bedroom in the Tuileries, arriving at the Louvre in 1804.

During Malraux’s aforesaid White House visit, Mrs. Kennedy had cooed in his ear that it would be just lovely if Americans had the chance to behold this artistic marvel. It would be a gesture of amity and goodwill, she told him, beneficial to both countries. Malraux was receptive, but he knew that it would be difficult to convince President Charles de Gaulle and the administrators of the Louvre to permit it to leave temporarily. Still, had not the Americans shown themselves willing to do the same with the Hope Diamond?

In time, Gallic resistance was worn down. The Mona Lisa (known as La Joconde in France) was packed in a temperature-controlled box, accompanied by armed guards aboard the SS France. It crossed the Atlantic Ocean and arrived in New York on December 19, 1962. From there, the painting was placed in an armored van and driven straight to the National Gallery—through New Jersey, Delaware and Maryland—with sirens screaming and red lights flashing.

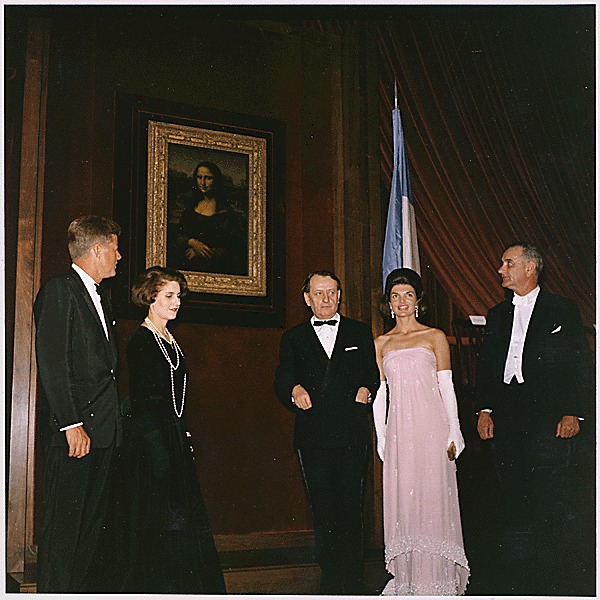

Oddly enough, National Gallery director John Walker originally opposed the exhibition; he did not want the security headaches and knew that any problems that arose would be his problems. Walker need not have worried, as the Mona Lisa was installed behind bulletproof glass in the gallery’s West Sculpture Hall. It was unveiled on January 9, 1963 (three months after the Cuban missile crisis) to coincide with the opening of the 88th Congress. Every member was there, along with the First Couple, Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson and his wife Lady Bird, the Cabinet, all nine Supreme Court justices and the presidents of several major universities.

The Mona Lisa spent three weeks in the nation’s capital and a month at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. More than 1.5 million people saw the painting, and it was front-page news in a country where the arts, as Mrs. Kennedy liked to say, were treated like a stepchild. The two exhibitions were a roaring success. Our Francophile First Lady had pulled it off, demystifying the museum-going experience for “average” Americans and showing that art was not just the domain of snobby connoisseurs. Of course, the snobby connoisseurs were also happy to get the chance to look at Leonardo’s painting.

It was back at the Louvre in March, rendering all that French hand-wringing unnecessary. Andy Warhol lost no time in creating Colored Mona Lisa which was put up for auction at Christie’s on May 13, 1963. In keeping with Warhol’s pop-iconoclastic ways, he focused more on its fame and mythology than its formal qualities. Mrs. Kennedy’s triumph—indeed, there had been two—also sparked an academic treatise, John F. Kennedy and Leonardo’s Mona Lisa / Art as the Continuation of Politics by Frank Zollner and a book, Mona Lisa in Camelot / How Jacquelyn Kennedy and da Vinci’s Masterpiece Charmed and Captivated a Nation by Margaret Leslie Davis.

I was hoping to avoid any reference to “Camelot” here, but Davis chose to use it in the title of her book. Not long after the tragedy of Dealey Plaza, Mrs. Kennedy began polishing the legacy of her husband’s 1,000-day presidency, calling it Camelot. The Lerner and Loewe Broadway musical of that name (the story of King Arthur’s mythical world in which virtue and heroism reigned supreme) had been popular with JFK. Whether or not the fantasy she spun has a shred of truth, the Hope Diamond and Mona Lisa events must be regarded as among Camelot’s high-water marks.

3 Comments

Fascinating, Richard! I was able to see the King Tut exhibit and the Dead Sea Scrolls, but seeing the Hope or Madam Lisa Gioconda would never have been in my range. A great article such as this can combine history, intrigue, international politics, and a vignette of a first-class First Lady. All that was missing was baseball. For another day.

I try, Dex, I try!

Thanks for reading and commenting.

Richard, you have been a living example of the historic fact, “One person can change the course of history” with your jikji initiatives…There are so many people in all walks of life, in all levels of society that have made major contributions to mankind… be it in science, in medicine, in research, in government, in art, in sports, etc… it takes one person sometimes to over come , to discover, to postulate, to discern…Jackie O was one of these people. With all the angst shared by both France and US museum directors, she was able to make the trade of art pieces happen. We need to bear this in mind always, our decisions can and do affect history. Very inspiring.

Add Comment