The logo of the Coast Guard air station in Salem, Massachusetts features a witch riding a broom. Same for police cars. There is a Witchcraft Heights Elementary School, and the mascot for Salem High School is, naturally, the witch. Salem, known as “the witch city,” erected a six-foot-tall statue of Elizabeth Montgomery in 2005; she, too, is riding a broom surmounted by a crescent moon. Montgomery is  remembered for starring as Samantha in the TV show Bewitched. Brunch, lunch and dinner are available at the Witches’ Brew Café in Salem’s historic district.

remembered for starring as Samantha in the TV show Bewitched. Brunch, lunch and dinner are available at the Witches’ Brew Café in Salem’s historic district.

Please do not accuse me of lacking a sense of humor because I can tell a mindless joke as well as anybody. But I do not find what took place in that New England city 328 years ago remotely funny. More than 200 people were accused of—in one form or another—consorting with the devil, 30 were found guilty and 20 were put to death. I will name them: Bridget Bishop, Rebecca Nurse, Sarah Good, Elizabeth Howe, Susannah Martin, Sarah Wildes, George Burroughs, George Jacobs Sr., Martha Carrier, John Proctor, John Willard, Martha Corey, Mary Eastey, Mary Parker, Alice Parker, Ann Pudeator, Wilmot Redd, Margaret Scott, Samuel Wardwell Sr. and Giles Corey. Intense social, legal and religious pressure compelled some to confess to the crime, but none were in fact witches. All were victims. They ranged from a scabrous beggar woman (Good) to a kindly great-grandmother (Nurse) to a wife-abusing minister (Burroughs).

Accusations were made against them on the basis of what the modern mind regards as the flimsiest of proof. In February 1692, 11-year-old Abigail Adams, her 9-year-old cousin Betty Parris, 18-year old Elizabeth Booth, 12-year-old Ann Putnam, Jr. and an Indian slave named Tituba began having fits, sometimes interrupting church services. They fell into trances, jumped about in spasms, screamed insensibly and made outlandish claims. Their alleged dreams and visions (“spectral evidence”) of neighbors committing nefarious acts were taken at face value by the authorities.

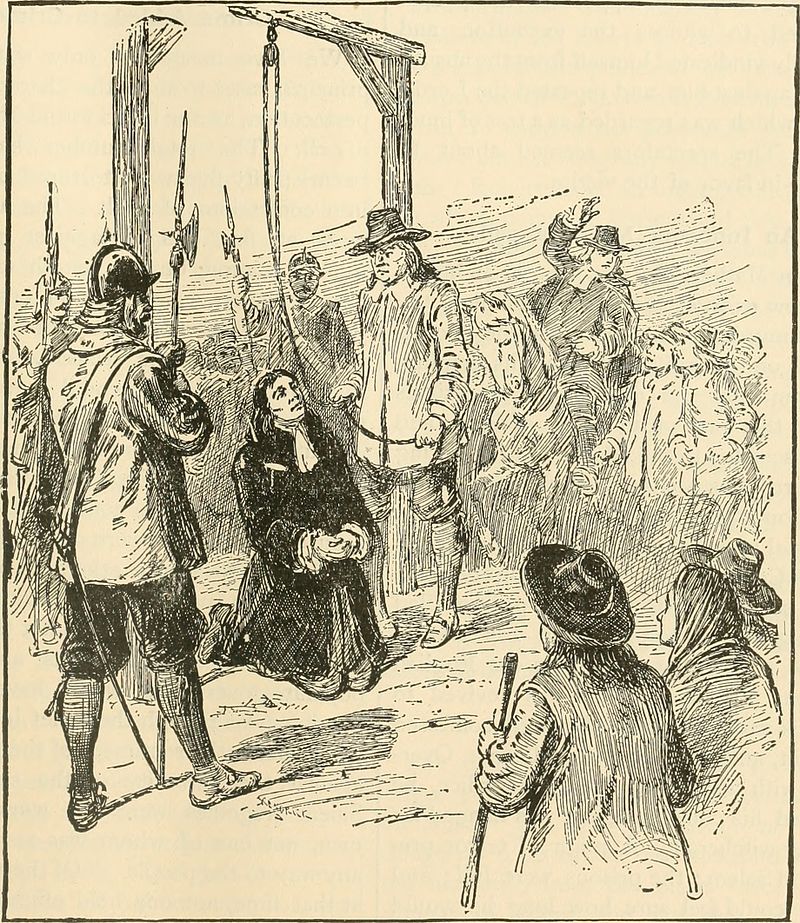

Thoroughly frightened and bewildered, Bishop, Nurse, et al. were brought before grand juries and then a special court headed by William Stoughton. If found guilty, a person would be bound hand and foot, placed in a cart and hauled to some crudely erected gallows. A prayer was said on  behalf of his or her soul, a hood placed over his or her head and a noose around his or her neck. The executioner kicked the stool on which the victim stood, and death came painfully. There was one exception, Giles Corey, who refused to enter a guilty or not-guilty plea. His punishment consisted of having a series of boulders placed on his body until he expired.

behalf of his or her soul, a hood placed over his or her head and a noose around his or her neck. The executioner kicked the stool on which the victim stood, and death came painfully. There was one exception, Giles Corey, who refused to enter a guilty or not-guilty plea. His punishment consisted of having a series of boulders placed on his body until he expired.

Keep in mind the setting in which such terrible events took place. The English Puritans had landed at Plymouth Rock barely three generations before. Very devout Christians, they thought the Protestant Reformation had not gone far enough and held doctrines that seem ludicrously stringent today. They abhorred Christmas and feast days, and listened to four-hour sermons heavy on hellfire and brimstone.

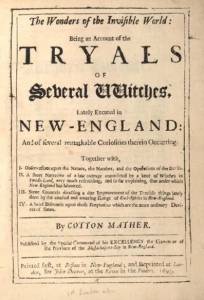

Administration of justice then was clumsy and had no safeguards for defendants. The Salem witchcraft trials, the most notorious case of mass hysteria in colonial American history, might have been halted in their tracks if Increase Mather and/or his son Cotton had been on the ball. The old man, president of nearby Harvard College for 20 years, wrote a book defending the judges and the trials albeit with a word or two of caution; he was hedging his bets. His son wrote an astounding 437 books, some of them about the reality of witchcraft.  Influential in the formation of the court and fully supporting the accusers, known as “the afflicted,” he sermonized and insisted that the devil’s fevered activity in Salem was somehow proof of divine sanction. Neither of the Mathers seems to have had any qualms when he saw those bodies swinging.

Influential in the formation of the court and fully supporting the accusers, known as “the afflicted,” he sermonized and insisted that the devil’s fevered activity in Salem was somehow proof of divine sanction. Neither of the Mathers seems to have had any qualms when he saw those bodies swinging.

Skeptics and protesters took their lives into their own hands. After all, to do so was to aid and abet Satan, was it not? Thomas Brattle, Robert Calef, Thomas Maule, William Milborne, Robert Pike and John Wise all dared to question the madness. It did not stop until the wife of Massachusetts Governor William Phips was accused. Phips, who was somewhat complicit in those 20 deaths, finally acted with a firm hand. He abolished Stoughton’s court and freed the people who had been languishing in the Salem and Boston jails.

Salem, I sense, is still living down the horror of the witchcraft trials. It started within five years when local ministers called for penance and fasting, and jurors who had voted to convict and send innocent people to the hangman sought forgiveness. Several of the accusers disappeared from the historical record, although we know Betty Parris lived until 1760; her four children must have had some inkling of the awful things she had done in her youth. The only one to publicly apologize for her role in the witchcraft trials was Ann Putnam, Jr. On August 25, 1706, she stood before the congregation of Salem Church and said, “I desire to be humbled before God for that sad and humbling providence that befell my father’s family in the year about ninety-two; that I, then being in my childhood, should, by such a providence of God, be made an instrument for the accusing of several people for grievous crimes, whereby their lives were taken away from them, whom, now I have just grounds and good reason to believe they were innocent persons; and that it was a great delusion of Satan that deceived me in that sad time, whereby I justly fear I have been instrumental, with others, though ignorantly and unwittingly, to bring upon  myself and this land the guilt of innocent blood… I desire to lie in the dust, and to be humbled for it, in that I was a cause, with others, of so sad a calamity to them and their families; for which cause I desire to lie in the dust, and earnestly beg forgiveness of God, and from all those unto whom I have given just cause of sorrow and offense, whose relations were taken away or accused.”

myself and this land the guilt of innocent blood… I desire to lie in the dust, and to be humbled for it, in that I was a cause, with others, of so sad a calamity to them and their families; for which cause I desire to lie in the dust, and earnestly beg forgiveness of God, and from all those unto whom I have given just cause of sorrow and offense, whose relations were taken away or accused.”

A key magistrate around that time was John Hathorne. His great-great-grandson, Nathaniel Hawthorne (born in 1804 in Salem), would gain fame for writing The Scarlet Letter and The House of the Seven Gables. In both, he wrestled with issues of witchcraft, public humiliation, guilt, repentance and sin.

In 1892, bicentennial of the trials, the city started taking a light-hearted approach to these historical events and promoting what is called witchcraft tourism. “Haunted Happenings” on Halloween night draws ever bigger crowds: 250,000, if you can believe that.

If I had the chance to visit Salem, I would skip the statue of Elizabeth Montgomery and the Witches’ Brew Café, and go straight to the Salem Witch Museum on Washington Square North. As soon as I stepped into that facility, I would ask for the curator and protest its name. Is that repugnant term really necessary? All of the victims have long since been exonerated. At the very least, put it in quotation  marks. That’s what Koreans do with the touchy issue of “comfort women.” Leaving the museum, I would walk to Proctor’s Ledge. It sits at the bottom of what is known as Gallows Hill. Here, according to local historians, the 19 hangings took place. (Giles Corey was crushed in a field adjacent to the prison where he was held, now the Howard Street Cemetery.) A suitably respectful and dignified memorial was erected at Proctor’s Ledge in 2017. I will pass on the silly nonsense, remembering instead that Salem symbolizes persecution, fanaticism and a mad rush to judgement.

marks. That’s what Koreans do with the touchy issue of “comfort women.” Leaving the museum, I would walk to Proctor’s Ledge. It sits at the bottom of what is known as Gallows Hill. Here, according to local historians, the 19 hangings took place. (Giles Corey was crushed in a field adjacent to the prison where he was held, now the Howard Street Cemetery.) A suitably respectful and dignified memorial was erected at Proctor’s Ledge in 2017. I will pass on the silly nonsense, remembering instead that Salem symbolizes persecution, fanaticism and a mad rush to judgement.

9 Comments

While doing my family genealogy, it appeared that Sarah Wildes was my 9th great grandmother. There is so much information about her that I really read up on her and became enamored by her. She was hung with four others. Here is what I concluded. Maybe she was a little free spirited. Maybe she was arrested for public indecency a couple of times. But she was no witch. A husband and wife, that’s it, accused her of being a witch. That’s all it took. That was a time before due process. As it turns out, about 30 genealogies on Ancestry tie my 5th great grandfather George Wiles to Sarah Wildes. They are all incorrect. George was German, Sarah was English. I would have been proud to descend from her but it’s not true. And she was wronged.

OK, regardless of genealogy issues…. This is a complicated story, and I had to simplify it considerably. For example, “witches” were arrested in many other New England towns–not just Salem. Also, there were a few who died while in jail (in horrible conditions). And finally, many of the records from Salem in 1962 were destroyed in the years to come. Such was the feeling of shame and wishing it had never happened.

Feels a bit like the mass hysteria that has taken over the minds of Trump supporters… people just never learn.

This has nothing to do with Trump or the people who hate him.

Thanks for replying to the person with TDS. I was going to say the same thing.

I have heard that ergot poisoning from tainted rye might have fueled the whole process. Based on my own observations, the age and sex of the accusers have a lot to do with the whole mess also. Girls that age are vicious and like to roam in packs. Add to that a deeply fundamental Protestantism based on nothing, and you have a recipe for disaster. I also agree that the city of Salem is capitalizing on the executions of innocents.

Vicki, I had forgotten about that “tainted rye” theory. Quite possible! I wonder why the author made no reference to it. I think the Mathers deserve a lot of the blame. They were possibly the most important people in that community and could have put a stop to it before a single person was unfairly convicted and sent to the gallows. There is a statue of Cotton Mather in downtown Boston, and maybe the cancel-culture crowd can go and tear it down.

You can’t easily accused of someone of being a witch a witch up to this day. Like in this story the judgement were being based on my words against your words. Purely accusations but no solid evidence for sure to testify fhat these accused are really witch.

Yes, this is true. But the attitude and mentality then were so very different from today. Sometimes we forget how “modern” our attitudes are. What happened in Salem was a huge tragedy.

Add Comment