Since the U.S. Supreme Court was established in 1789, a total of 113 men and women have served as justices. George Washington appointed John Jay as the first chief justice, and Donald Trump nominated Neil Gorsuch early last year. The former required no confirmation, whereas the latter took his seat on the bench only after a bruising battle in the Senate. The Supremes—and I’m not talking about the 1960s Motown vocal group led by Diana Ross—have ultimate and discretionary jurisdiction over all federal and state court cases, and are sworn to uphold the Constitution. Some justices have been wise, brilliant and dedicated, and others less so. One (Samuel Chase) was impeached, and quite a few were little more than presidential cronies who viewed a spot on the Supreme Court as a sinecure. Issues of geography, ideology, religion, demography and more recently gender are considered in Supreme Court nominations, not to mention political affiliation; a Democrat will rarely pick a Republican or vice versa.

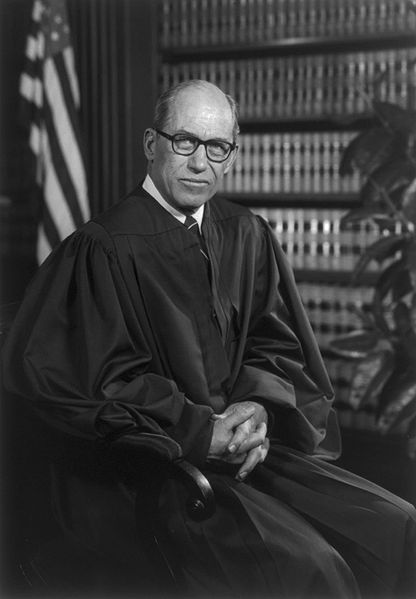

Who, you may wonder, is my favorite Supreme Court justice? It’s not the cantankerous, anti-Semitic James C. McReynolds or Clarence Thomas (coasting since 1991). Neither should have gotten close to the nation’s highest court. Nor is it Tom C. Clark, a native of Dallas who graduated from the University of Texas. John Marshall, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., Felix Frankfurter and Benjamin Cardozo have their fans. All richly deserved being called “your honor.” But the one I find most compelling is Byron “Whizzer” White, whose tenure went from April 12, 1962 to June 28, 1993.

Sports or academia?

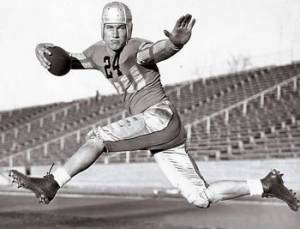

Born the son of a beet farmer in 1917, he enrolled at the University of Colorado, was elected student body president and earned every academic honor possible. White had brawn to go with his brain, playing football for the Buffaloes. An All-America running back and second in Heisman Trophy voting in 1937, he also played baseball and basketball at CU. During his three-year pro football career, he led the NFL in rushing twice. White gave up athletics, however. He won a Rhodes Scholarship, studying at the University of Oxford. He came back to the U.S. and entered Yale Law School. Before he could get his LLB, World War II had begun to rage. As a naval intelligence officer in the Pacific theater, White won a couple of Bronze Stars prior to finishing his legal education at Yale—magna cum laude, of course.

A law clerk to Chief Justice Fred Vinson, he went home to Colorado and built a thriving private practice. President John F. Kennedy, whom he had befriended during the war, brought White back to Washington to serve as deputy attorney general. In that role, he sought to protect Freedom Riders in 1961 and dealt fearlessly with Eugene “Bull” Connor, Birmingham’s notorious commissioner of public safety. Kennedy nominated him to replace Justice Charles Whittaker (widely regarded by modern scholars as unfit for the bench).

White’s legal thinking

White spent three decades on the Supreme Court, and he was a centrist, a swing voter. The right-wingers called him a liberal, and the left-wingers called him a conservative. He dissented from Chief Justice Earl Warren’s “right-to-remain-silent” Miranda case, consistently voted against abortion rights, supported the Court’s post-Brown attempts to fully desegregate public schools and favored so-called affirmative action to remedy lingering racial injustice. Gay rights advocates did not think highly of him. Attorneys appearing at the Supreme Court could expect to receive a grilling from the sharp-minded White. He wrote nearly 1,000 opinions during his service on the high court. Short on rhetorical flourishes, they tended to get to the point.

Still vigorous in 1993, White chose to retire because he felt he should make way for a younger person. Many justices have stayed too long (William Douglas, William Brennan, Thurgood Marshall and Lewis Powell, for example). After his death in 2002, then-Chief Justice William Rehnquist likened White to Sophocles, the writer from ancient Greece: “He saw life steadily, and he saw it whole. All of us who served with him will miss him.”

White is well remembered. In 1954, he was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame. Since 1967, the NFL Players Association has given the Byron “Whizzer” White Man of the Year Award to the player who does the most notable charity work. He posthumously received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and the Tenth Circuit Federal Courthouse in Denver is named after him, as is CU’s Center for the Study of American Constitutional Law.

6 Comments

Well done, professor. You made strong points for Mr. White having been a solid member of SCOTUS. In my lifetime, Mr. Alito and Mr. Scalia have been my favorites. Both men have shared my conservatism and wry humor. Better yet, both men displayed no strident antagonism against their ideological fellow justices.

In my own life, I’ve enjoyed many delightful conversations with liberals, ultra-libs, and assorted lefties. Once we have agreed to avoid “third rail” topics, grand times have occurred.

THank you, Darrell. Let’s stay off that darn third rail!

Good introduction to a complex man! I hope you write another piece on him and delve into some of his legal thinking a bit more. I’ve often thought that the Miranda issue should be one that both the left and the right should find more agreement on. Shouldn’t the ‘right to remain silent’ appeal to those who believe in curbing government overreach and those who start from a human rights/racial justice framework?

Good point, James. But these essays are by definition summaries. I left out a lot of things, interesting things, from White’s early days, his athletic achievements and his time on the Supreme Court. I am no legal scholar, hahaha! How is your book coming along?

another interesting story, Richard–an overview of Mr. White and the difference in having a seat on the Supreme Court of the US, then and now”.

Richard- I enjoyed your article. II is always interesting to read about athletes who have made a successful transition into lives of public service. His opinions on social issues do seem a bit paradoxical. Why would someone support affirmative action yet be opposed to the Miranda Amendment?

Add Comment