It’s interesting to realize how ambitious the Japanese were just over eight decades ago. Consider the countries they occupied or subjected to military force: Korea, China, the Philippines, Burma (Myanmar), Thailand, Singapore, Malaya, Formosa (Taiwan), the United States, French Indochina (Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos), Wake Island, Guam, Hong Kong, parts of British India and the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia). My focus is the latter, specifically the eastern half of the island of New Guinea—what we now call Papua New Guinea and even more specifically, the village of Rakunai on the much smaller island of New Britain.

Starting in 1884, New Guinea had been a protectorate of Germany. But early in World War I, it came under the military administration of Australia, a status soon upheld by a mandate from the League of Nations. Japanese forces took over in 1942, thinking New Guinea would be a good jumping-off place for an invasion of Australia. Although that was eventually dismissed as impractical, the Japanese held tenaciously to New Guinea. Fierce fighting occurred between Allied forces—generally the Aussies and Americans on one side and the Japanese on the other—in the Battles of Port Moresby (the nation’s capital today), Rabaul, Buna–Gona, Milne Bay, Roosevelt Ridge, Wau, Hollandia, Bougainville and more than a dozen others; some of those battles took place in malaria-ridden jungles. An estimated 240,000 soldiers and 15,000 civilians lost their lives before the Japanese finally understood that they had suffered a crushing defeat.

The indigenous population of New Guinea was severely affected by this series of chaotic clashes; in some villages one in every four people lost his or her life as a result of direct military action, disease, starvation, being worked to death or murder, which includes the executions of 333 Christian church workers. This, then, is the backdrop for the truly heroic life of Peter To Rot, one of the Tolai people. (Papua New Guinea, or PNG, is one of the most ethnically and linguistically diverse places on earth.)

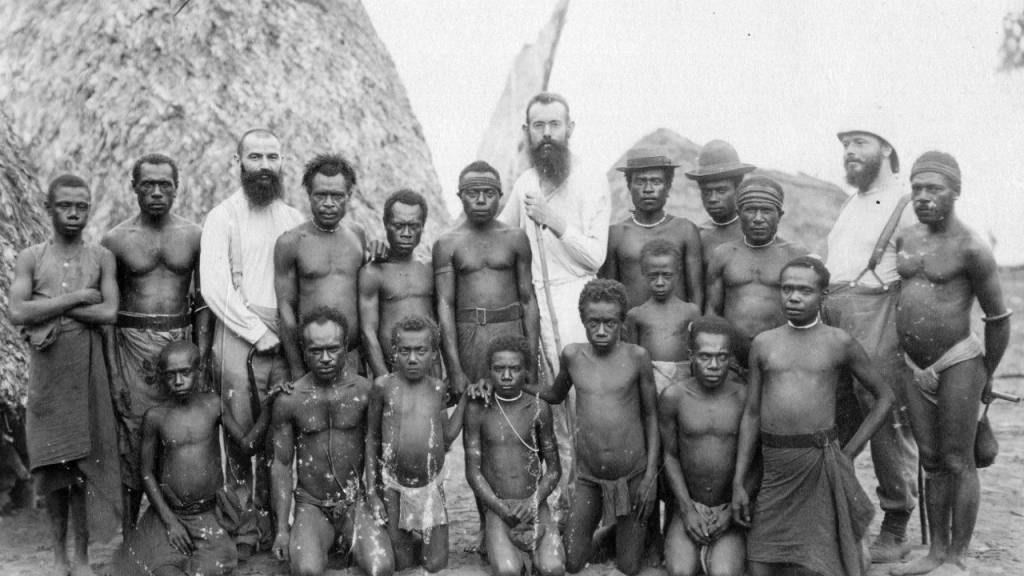

He was born on March 5, 1912, the third of six children to Angelo Tu Puia—a much-respected village chief—and Maria la Tumul. Both of his parents had become Catholics in 1898, abjuring centuries-old native religious beliefs involving animism and ancestor worship. After learning the basics of the catechism at age seven and serving as an altar boy, To Rot was sent to the mission school in his home village of Rakunai. Displaying rare maturity and spiritual awareness, he impressed the parish priest, Father Carl Laufer, who urged To Rot’s father to have him aim for the priesthood. Tu Puia demurred, suggesting that he study to become a catechist instead.

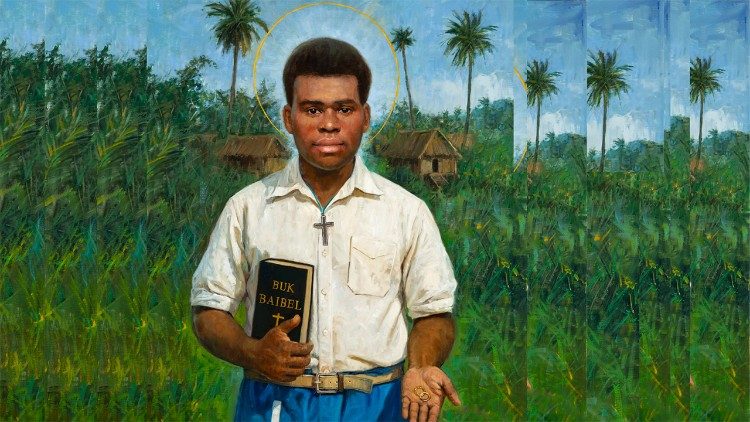

Accordingly, To Rot entered Saint Paul’s College in Taliligap, graduating in 1933. He performed his pastoral duties (educating Christian converts, conducting marriages and baptisms, burying the dead and preaching the Gospel) faithfully back in Rakunai. To Rot, who always wore the catechist’s cross and carried his Bible, attended the sick, poor and aged. In November 1936, he married a woman named Paula la Varpit. The wedding was held in a Catholic church, although they observed certain Tolai traditional customs. Nothing wrong with a little syncretism. Of their three children, one lived to an old age and thus was able to provide crucial biographical information about his illustrious father.

On January 4, 1942, those bloody samurais, the Japanese, invaded. While they interned foreign missionaries (such as Father Laufer), religious practice in New Guinea was allowed—for a while. By late 1943, however, it was restricted and then completely forbidden. Not only that, but the Japanese sought to reinstate polygamy and thus encourage the people to return to their earlier pagan traditions. Doing so, I can only surmise, would have made them more compliant to Nippon. To Rot, who had never stopped his religious work, would not abide this. He walked a fine line between accommodating the Japanese and an outright refusal to cooperate. To make matters worse, a married man named Metepa—a policeman employed by the Japanese in Rakunai—fancied a married woman named la Mentil and planned to kidnap her and make her his second wife. To Rot and the lady’s father intervened. It is a long and convoluted story, but the gist is that with the help of Metepa and a few other local turncoats (one of them, believe it or not, an older brother whom he had confronted over his polygamous activities), To Rot had become a bull’s eye for the Japanese.

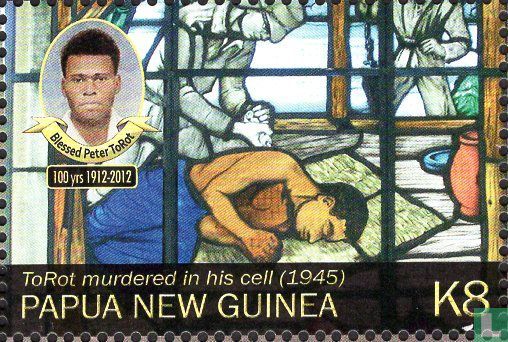

On Christmas Day 1944, he was working in his garden, planting vegetables that he intended to give to the Japanese as an act of charity. He was arrested, interrogated, beaten and locked in a small, windowless cell in the Vunaiara concentration camp. Two Christian leaders sought his release, to no avail. Had he only capitulated, he could have saved himself. His wife visited and begged him to come home and live a quiet life, but he would not. More mistreatment followed, capped by a lethal injection; a Japanese doctor said it was “medicine,” although To Rot was not sick. Knowing his end was near, he asked his mother and wife to bring his cross and best clothes so he could face God in proper attire. Peter To Rot died on July 7, 1945, barely six weeks before Japan surrendered, bringing World War II to a close. Buried in Rakunai’s Catholic cemetery, his funeral was held in silence for fear of irritating the Japanese soldiers.

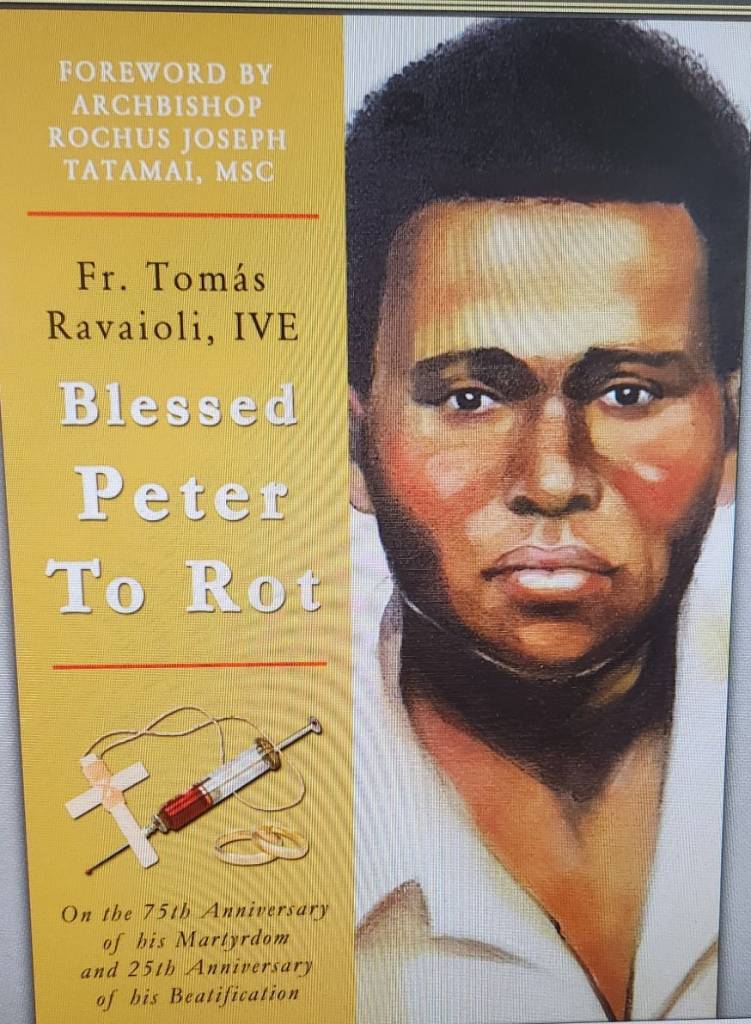

As a Protestant, I admit that the means by which a person is named a saint puzzles me. But I read that the process of To Rot’s canonization began in 1986, more than four decades after his death. A beatification ceremony took place on January 17, 1995, at John Guise Stadium in Port Moresby, and then on to the next stage. Some of the people who helped are Bishops Leo Scharmach and Albert Bundervoet, Cardinal Zen Ze-kium, Archbishop Francesco Panfilo, Fathers Fernando Clemente Santos and Tomas Ravaili and, most important, Popes John Paul II (who visited PNG in 1984 and 1995) and Francis (2024). I had thought that one was required to have performed at least two verifiable miracles to qualify, but not so. To Rot gets this highest honor in the Catholic Church because of the virtuous life he lived and the fact that he had been martyred in odium fidei (“in hatred of the faith”).

Pope Leo XIV will make it official on October 19 with a Canonization Mass in Vatican City conferring sainthood on the Blessed Peter To Rot and six other worthies: Ignazio Choukrallah Maloyan, Vincenza Maria Poloni, Maria Troncatti, José Gregorio Hernández, Carmen Rendiles Martínez and Bartolo Longo. Papua New Guinea’s first saint, To Rot is cause for considerable pride and celebration in that nation. His liturgical feast is affixed to the date of his death, July 7.

3 Comments

Thank you the article, good read. He did stand up for what he believed in to the end. I don’t know what the requirements are for sainthood either.

I appreciate you sharing the life of an honorable man who stood on principle in face of personal abuse. I believe the good among humankind far exceeds the evil but is not represented enough. When the daily news is overwhelming with despair I turn it off and I leave my house to go to local stores where I observe everyday real people interacting with kindness and respect with one another. The rudeness and disrespect on broadcast and social media disappear in most common human interactions. Removing human contact seems to empower underlying discontent, bias, and prejudice. Thank you for ‘introducing’ Papua New Guinea to me. I ignorantly only thought of it as the story of the early missionary that was killed by the indigenous people in the old black and white news reels. No idea of the Christian presence and heritage you illuminated.

Thank you for the history. This world can be interesting and cruel, sometime at the same time. This man defended and practiced his faith despite the dangers. That is what Jesus would have done. He is a positive example for his people to follow. That includes the rest of us, whether a believer or not.

Add Comment