With UN troops (American, South Korean and others) having busted out of the Pusan Perimeter and the Incheon Landing an unmitigated success, Seoul was retaken after a nine-day battle in late September 1950. North Korean troops had once seemed invincible, but the tide had turned. Now, battered and tattered, they were on the run. Having achieved the primary goal of reestablishing the 38th parallel as the border, U.S. President Harry Truman, General Douglas MacArthur and the Joint Chiefs of Staff agreed to keep going. The DPRK—with the backing and encouragement of its Communist allies Russia and China—had started this conflict, so why not give Kim Il-sung’s boys a firm spanking? ROK President Syngman Rhee was intent on nothing less than complete unification of north and south.

The obvious first goal was the capital, Pyongyang. On the way there, they captured Kaesong (capital during the Goryeo dynasty), Sariwon and Hwangju. Although they encountered stiffer resistance during the Battle of Pyongyang, the outcome was never in doubt. For one thing, Kim and the rest of the DPRK leadership had by then withdrawn further north to Kanggye. He was also making discreet inquiries to Mao Zedong about setting up a government-in-exile in China if things got too hot.

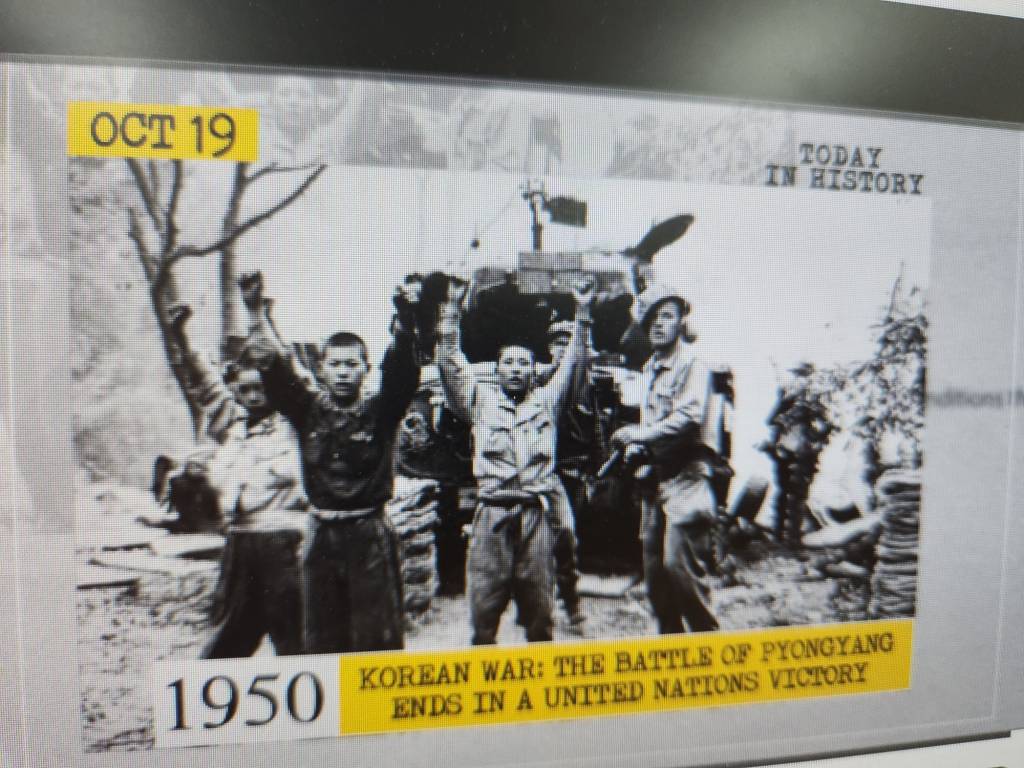

Intelligence reports indicated that fewer than 8,000 effective soldiers had been left behind to defend Pyongyang. There is no need to specify which platoons, brigades, regiments and divisions were involved in this three-day affair, but it was a clear-cut victory. UN forces, having crossed the Taedong River, soon held the airport, City Hall, Kim Il-sung University, the North Korean Military Academy and other governmental entities. General Walton Walker moved into Kim’s former headquarters and made himself at home. Although the self-styled Sun of the Nation, Fatherly Leader and Eternal Leader of Juche Korea had outlawed Christian churches in his first five years in power, a few remained, and their bells rang lustily. Some people waved the Taegukgi, showing where their sympathies resided; to them, October 19, 1950 was a day of jubilant liberation.

From the air, wrote one American journalist, “The besieged capital of North Korea looks like an empty citadel where death is king, a blackened community of the dead, a charred ghost town from which all the living have fled before a sudden plague.” On the ground, as we have seen, it was a very different story. The men under Walker’s command found the city festooned with Communist and Soviet slogans and propaganda, and pictures of Lenin and Stalin displayed copiously.

For six weeks, UN forces held Pyongyang, and it may have appeared that the war was, in effect, over. (MacArthur, always given to grand pronouncements, said the boys would be home by Christmas. There were also discussions about how a unified post-war Korea would operate.) Certainly, when Rhee spoke there on October 30, he said as much. No, Kim was not going to realize his utopian visions for the entire Korean Peninsula, and evidently not even for the north. This was a savage war on both sides. DPRK forces had killed thousands of “enemy” prisoners before going north, and many of those captured by UN forces were, shall we say, treated rather roughly. ROK counterintelligence officers, whose job it was to root out and eliminate members of the Workers’ Party, did so with zeal. North Koreans would later claim—surely with some degree of hyperbole—that 15,000 of their people had been massacred in Pyongyang during that brief span.

Alas, huge numbers of Chinese soldiers had already crossed the Yalu River and begun to inflict terrible damage on American Marines and their ROK partners up close to the border. The trajectory of the war changed once again. By December 6, the Pyongyang idyll was over because the Chinese and North Koreans had pushed southward, blood in their eyes. An endless line of vehicles and fearful people—those who had gleefully waved the Taegukgi a few weeks earlier, for example—were intent on reaching relative safety below the 38th parallel. Even before that process was finished, MacArthur ordered the city to be firebombed. Throughout the war, the U.S. Air Force controlled the skies, and those B-26s and B-29s were merciless, sometimes flying as many as 1,400 sorties in a single day. By the time the armistice was signed in July 1953, more than 75 percent of the buildings in Pyongyang had been bombed to rubble, and it was even worse in Kyoimpo, Hamhung, Chinnampo, Wonsan, Hwangju and Sinanju.

Then, as now, Pyongyang was a city apart. The flames had barely been quenched before a general plan for restoration was announced. Soviet-trained architects designed a series of buildings marked by modernist, futurist and brutalist styles. It has been described as a raw urbanscape, one heavy with concrete, blending Russian and Korean influences. Home to just 200,000 people in the depths of the war, it now has more than 3 million.

In his review of Robert Collins’ Pyongyang Republic: North Korea’s Capital of Human Rights Denial, Andrew J. Nathan has written, “The survival of the North Korean regime depends partly on the way it distributes material privileges in a series of rings around a dynastic core. Around 200,000 high-level elites live in central Pyongyang in nearly First World conditions. They must continuously demonstrate absolute loyalty to the ruling Kim dynasty or suffer instant banishment to a labor camp. Mid-level officials are trusted even less, live farther out, and contend with some hunger and cold. In the next ring resides what Collins describes as a ‘lesser elite,’ whose members are grateful for the limited access they enjoy to food, housing, health care, running water, electricity and heating, because they know about the extreme deprivation suffered by the 85 percent of the population that is not allowed to live in the capital city.”

4 Comments

Thanks Richard for giving us a short, unpolitically aimed perspective, of what happen after Pyongyang was taken and then, left to the Marxist-aimed North Koreans. Surely, to engage in a long war with China and North Koreans together, would be too expensive and lives-costly for Americans. Unfortunately, the logical and pragmatic decission taken then was not learned or taken in account in the following decade, in Vietnam.

Your text is interesting, I hope that the peoples will live in peace with each other, that there will be no more wars and that people will not suffer anymore. I heard that in North Korea the population suffers a lot from hunger and the living conditions are disastrous. Before God we are all equal, no one deserves this. I want peace in the world!

Thanks Richard. Well written. The Korean War is not understood well by the American people. I need to do more reading myself.

My Dad was a Combat Engineer. He was on the front lines all the way up and all the way back. He came home with a Bronze Star. Like many soldiers from WWII he never talked about the war. I think he may have suffered from PTSD.

Very interesting, particularly of the yo-yo. I also found the description of Pyonghang’s housing by class interesting. It seems to provide a stage by which a large number of citizens can fester.

Trump’s willingness to meet with Kim seems a good thing from my perspective, but I wonder if it establishes Kim and his ego as world stage members.

I have to think there will be no progress between our two heads of state unless Kim is so acknowledged on the world stage. On the one hand nuclear presence seems to make him unwilling to talk in substance. On the other hand, how long can he and his family enjoy his privilege and lifestyle.

Time will tell. I hope we do not run out of it.

Add Comment