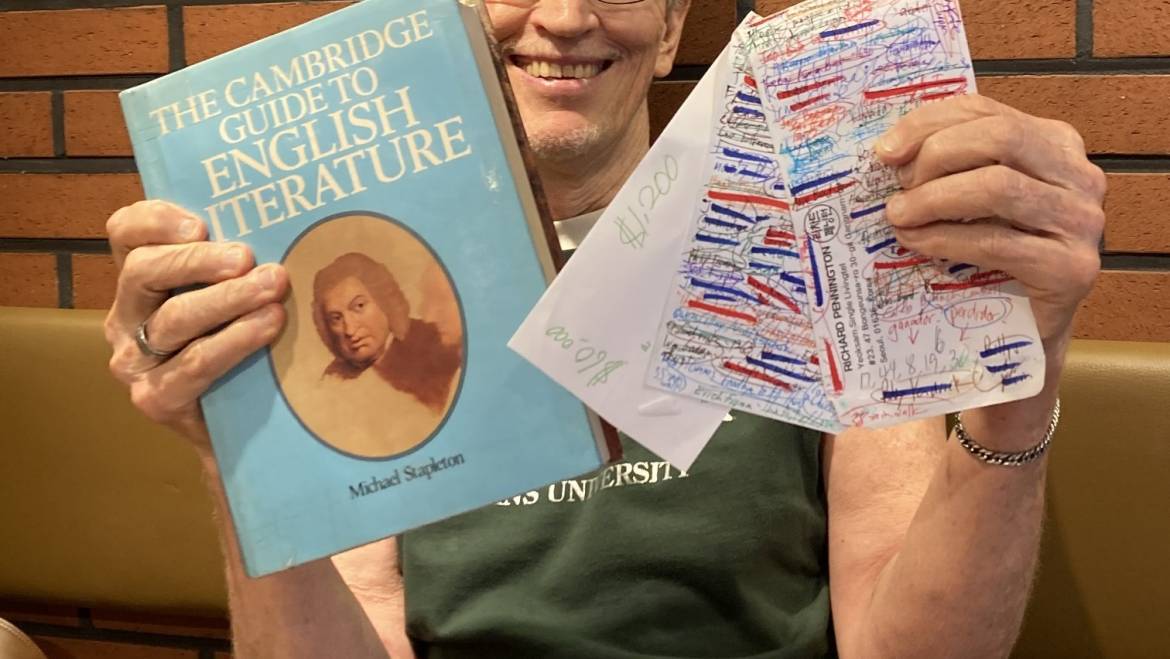

I paid 10,000 won ($7.37 at the current exchange rate) for a somewhat battered and tattered copy of this 992-page tome, published by Cambridge University Press in 1983, at a used book store in the Hongdae district of Seoul on June 19. I started reading it on July 7 and finished it yesterday morning. Now, heavily underlined and annotated, it has an honored place in my library. CUP has also published The Cambridge Guide to Literature in English, a completely different book; I am not about to attempt that 1,275-pager, no thank you.

On the cover is a drawing of Samuel Johnson, the essayist, poet, biographer, lexicographer and all-around brilliant Englishman. And on the back is an illustration from the late 14th century manuscript of Pearl, an alliterative poem now reposing in the British Library. I had never heard of Pearl before, but Stapleton tells us that it is a lament for a dead baby girl, that the unnamed poet wanders in the garden where she lies buried, falls asleep and dreams that he meets her, grown to maturity. She reproaches her father for grieving too much and says that she is in a blessed state. The theme of spiritual crisis and reconciliation to loss is raised to the highest level of expression in one of the masterpieces of English medieval poetry.

As I made my way through this book, I kept marveling at how well Stapleton knew his subject. I looked him up and found that he is a native of Dungarvan, Ireland who lived between 1923 and 1994. An autodidact, he left home at age 12 to work as an assistant to a butcher—slicing, chopping and packing meat! Even while working at that bloody occupation, he read voraciously in the fields of literature and music. Stapleton became knowledgeable enough to be hired as a proofreader at Oxford University Press before moving up to higher editorial positions. Edith Sitwell, one of the people listed in his book, knew him and offered encouragement. In addition to this one, he wrote several books on ancient and Oriental mythology.

It is obviously an immense book and quite an accomplishment for Stapleton. His purpose, he said in the introduction, was to provide easy reference to the great treasure-house of poetry, fiction, drama and satire which is one of Western civilization’s lasting achievements. Stapleton gave himself a wide remit: anything written in this language by people in Great Britain (England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland), the United States, Canada, India, South Africa, the West Indies and even Nigeria.

It may seem ungracious to issue complaints about the work of this very industrious polymath, but I have three. First, since I am a nonfiction guy through and through, I wish Stapleton would have included more history and biography/historians and biographers, and fewer novels, plays and poems/novelists, playwrights and poets. Second, the book was much too UK-centric. How many times did he start an entry by saying that some author was born in London (Manchester, Liverpool, Dublin, Edinburgh) and was educated at Eton (Harrow, Westminster, Winchester) and then Oxford (Cambridge, Trinity) and so on? Too many. Forgive me for sounding like a homer myself, but the entries for the USA seemed to be overwhelmingly from Massachusetts and New York. As for Texas writers, I found but two—Andy Adams (The Log of a Cowboy) and Katherine Anne Porter (winner of the 1966 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction). J. Frank Dobie, June Arnold, Roy Bedichek, Walter Prescott Webb, Dorothy Scarborough and Frank Buck were worthy of inclusion or at least consideration, not to mention my great-grandmother, Mamie Wynne Cox (The Romantic Flags of Texas). Finally, I think he wasted too much time telling us the plot of so many books and plays. I confess to having skimmed the long ones.

Enough picayune quibbles. I solemnly aver that The Cambridge Guide to English Literature was enjoyable and informative, and the 300-odd photos and drawings successfully brought to life the great literary figures of the past and the ages in which they lived. Stapleton included two well-crafted essays, “The English Language” by Barbara M.H. Strang and “The Bible in English” by C.H. Sisson. No doubt, I learned a lot from reading this book. Permit me to list 14 somewhat randomly chosen fascinating facts I picked up along the way. They are as follows:

Irish poet William Butler Yeats made five rather lucrative tours of the USA between 1903 and 1932, speaking mostly at prominent universities.

Wulfstan, the archbishop of York, was one of the major writers of the late Anglo-Saxon period in England. He also helped suppress the slave trade that had long operated between England and Ireland.

Billy Budd was left unfinished at Herman Melville’s death in 1891, then revised and published in 1924. It is just as famous as Moby-Dick—according to the author. The critics agree that it is a classic, but there is no way it ranks as highly as Melville’s tale of the one-legged captain Ahab and his obsession with catching a certain whale. Stapleton could not have been serious.

Bleak House, by Charles Dickens, was first published in 20 monthly installments, between March 1852 and September 1853. Perceived by some as an attack on the legal profession, it nonetheless spurred judicial reform in England.

The Connecticut Wits was an American literary group centered in Hartford in the late 18th century. Mostly graduates of Yale University, they included Joel Barlow, Lemuel Hopkins, David Humphries, Timothy Dwight and John Trumbull. All but the latter had served in George Washington’s Continental Army.

Dashiell Hammett, who specialized in hard-boiled detective novels, suffered from Joseph McCarthy’s witch-hunt, did a stint in prison and died an early death.

England’s first antiquary was John Leland. King Henry VIII sent him out on a five-year tour to bring the country’s most important historical books and artifacts back to London. He was not entirely successful, but he did save many valuable manuscripts following the dissolution of the monasteries in the late 1530s.

She Stoops to Conquer, a comedy by Oliver Goldsmith, opened at Covent Garden in March 1773. A play that succeeds on every level, it is notable for being the origin of the phrase, “Ask me no questions and I’ll tell you no lies.” (I have used it myself numerous times.)

Welsh poet Dylan Thomas died at age 39 in New York City of too much adulation and too much drink.

Ben Jonson liked to criticize his friend William Shakespeare and make fun of his lack of classical learning. But when he died, Jonson said, “I loved the man and do honor his memory, just short of idolatry,” “There was more in him to be praised than pardoned” and “He was not of an age, but for all time.”

Blind Harry was a bard, a wandering minstrel who earned a living by reciting his poems in the castles of Scottish nobles in the late 15th century.

“Malapropism,” the incorrect use of a word in place of a word with a similar sound, whether unintentionally or for comedic effect, resulting in a nonsensical utterance, derives from Mrs. Malaprop, a character in Richard Sheridan’s 1775 play The Rivals.

Lord Byron was a poet and arguably the most prominent Englishman in the world when he sailed to Greece in 1823, eager to help in the fight against the infidel Turks. He was a born leader, and the factional disputes that had plagued the Greek rebels vanished as they rallied around him. There was even some talk of making Byron the king of a free Greece, but he caught rheumatic fever and died in early 1824.

Rudyard Kipling’s poem “If—,” written circa 1895, is an inspiring literary example of Victorian-era stoicism. It was so popular that Kipling got sick of reciting it.

Illustration accompany Pearl on back of Stapleton’s book…

Add Comment