To a large extent, we still adhere to the proverb “Of the dead, say nothing but good” which can be traced back to a Spartan named Chilon in the sixth century BC; the Latin version is De mortuis nil nisi bonum. As soon as a very fallible person dies, he or she is spoken of as practically a saint. This is true of all but the worst of humanity—the Neros, the Rasputins, the Hitlers, the Pol Pots. One of the rare people for whom it need not be applied, though, is Wayne Estes (1943ᅳ1965). From all I can gather, he was a great basketball player and an even greater man.

Born in Virginia City, Montana, he was raised in nearby Anaconda—the site of a huge copper mine that brought a century of riches along with death in the form of arsenic and toxic metals that spewed from a 585-foot-high smokestack. The son of a smelter, the 6′ 6″, 230-pound Estes was on the football, basketball and track & field teams at Anaconda High School (the “Copperheads”). Montana state champion in the discus and shot put as a senior, he accepted a scholarship offered by Utah State University with the hope of doing more of the same. He might have given Texas A&M’s Randy Matson a run for his money in the mid- and late 1960s, but that changed when he asked Aggies basketball coach LaDell Anderson if he could try out. Anderson was very pleased with what he saw.

During Estes’ freshman year in Logan, his somewhat pudgy body became sculpted, and he averaged 19 points per game; the guy had a deadly hook shot. Now, the varsity. The Aggies, not a member of any athletic conference at the time, went 20-7 in 1963 with Estes averaging 20.0 points and 9.5 rebounds per game. They had a 21-8 record in 1964 as Estes’ numbers rose: 28.3 points and 13.0 rebounds per game. They reached the NCAA tournament when he was a sophomore and junior, winning one game in the 1964 postseason (a 92-90 defeat of Arizona State) before bowing out. And as a senior, he was among the best in the college basketball world, scoring 33.7 points and collecting 13.7 rebounds per game. His name was mentioned with those of Rick Barry of Miami, Cazzie Russell of Michigan, Bill Bradley of Princeton and Gail Goodrich of UCLA.

The Ags, who went 12-12 in 1965, were not having a spectacular season. Prior to hosting the University of Denver on February 8, they had lost consecutive games to Brigham Young, Colorado State, Texas Western (national champs the next year), Arizona State and BYU again. But 5,000-seat Nelson Fieldhouse was packed with students and other fans eager to see if he might become the school’s first player—and just the 18th in college basketball history—to score 2,000 points in his career. It would not be easy, since he was still 47 points away. Then again, he had set a USU record of 52 points in a December game against Boston College. The Aggies’ forward/center rose to the occasion, scoring 48 points in an easy 91-62 victory. With Estes’ final bucket, Anderson called a time-out. The whole team gathered around Estes, lifted him on their shoulders and carried him off the court. USU fans, of course, roared with delight.

In post-game interviews, Estes was typically self-effacing. He credited his teammates and said he was fortunate to have set the record. The life of Wayne Estes at that point could hardly have been better. Enormously popular among fellow students, he was engaged to a vivacious Mormon coed (he was an Episcopalian) named Paula Bandy, he would soon graduate from Utah State, and he was expected to be a first-round pick in the upcoming NBA draft. He signed autographs, showered and went out with ex-teammate Delano Lyons and another friend to dine at a local pizza joint and discuss the game.

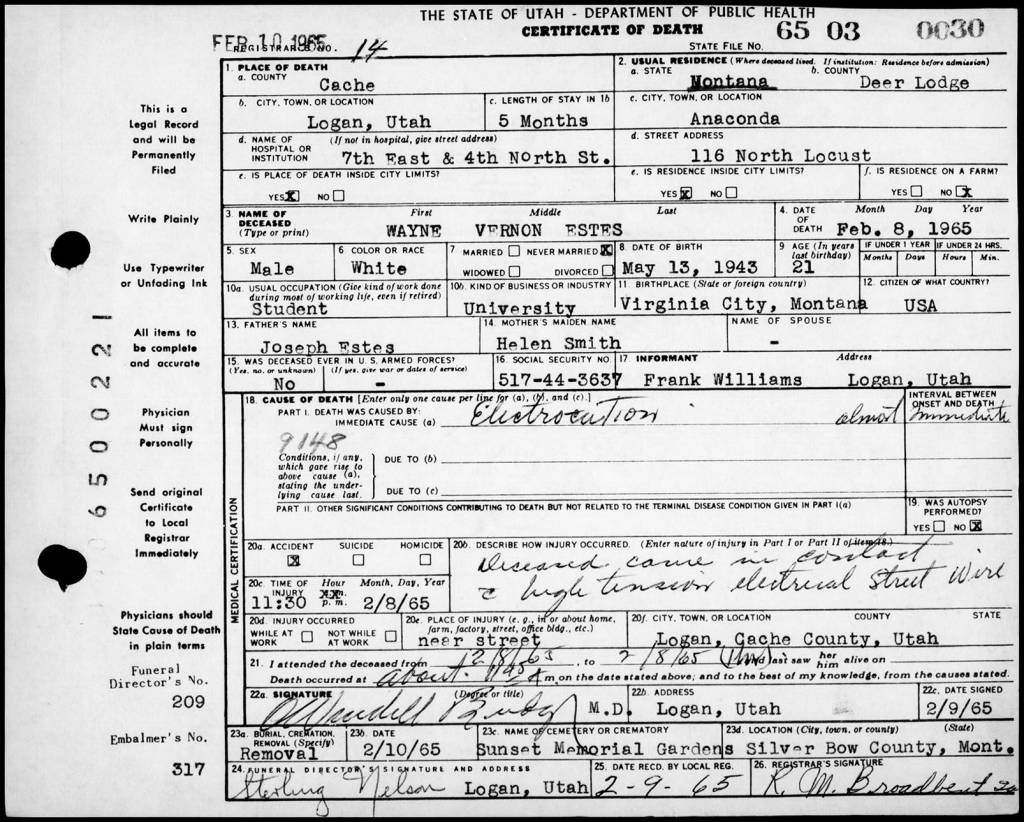

It was a snowy night on the Wasatch Range. On the way there, they passed by the scene of a gruesome car wreck, as a Ford Falcon was wrapped around a telephone pole. Coming back, their decision to get out and investigate led to an unfathomable disaster. A live wire was hanging down, and it touched Estes on the head. More than 2,000 volts of electricity shot through his body, smoke curled from his hands, and USU’s star hoopster fell to the concrete. An ambulance rushed him to William Budge Memorial Hospital, but he was dead on arrival.

The devastating news got to campus quickly. Students and faculty wept, businesses closed, and flags were flown at half-staff. “This generation of Aggies will never forget Wayne Estes,” said Dr. Daryl Chase, president of the university from 1954 through 1969. “He was the handsome youth in our midst…. He taught us lessons in humility in times of victory.”

If Logan was in shock after Estes’ death, it was even worse back in Anaconda. Four thousand people attended the service, and there was a long funeral procession to Sunset Memorial Park. His mother, Helen, was said to have never gotten over it.

Teammate Alan Parrish recalled Estes this way: “He was outstanding from the beginning. He was a great talent. And as a player, he was never selfish. He was always as interested in your success as in his own. He was the ideal teammate and a leader by nature. If he had a good game, you usually won, and he didn’t have many bad ones.”

“Wayne was a superstar,” said LeRoy Walker, a senior on the 1965 team. “Everyone loved him. He was never a selfish guy. He didn’t have an ego, and he didn’t have an agenda.”

Four coaches against whom he played—Bob Cousy of Boston College, Stan Watts of BYU, Fred Taylor of Ohio State and Jim Williams of Colorado State—spoke highly of him too.

The Aggies canceled their next two games before resuming play on February 18. Somewhat surprisingly, they did well in their final games, winning four and losing two.

Even in the worst of tragedies, life goes on. Paula Bandy eventually married another man, for example. But Estes was never forgotten in Utah and Montana. Of the 21 school records he held at the time of his death, he still has seven: career points per game (26.7), free throws made (469), consecutive games in double-digit scoring (64), points in a season (821), points per game in a season (33.7), points in a game (52) and rebounds in a game (28). His number, 33, has been retired. A classmate named Eleanor Olson wrote a rather hagiographic book entitled Wayne Estes: A Hero’s Legacy, and his brother Ron started the Wayne Estes Basketball Tournament (separate divisions for grade school students, high school students and adults) in Anaconda in 1984. The $9.7 million, 32,000-square-foot Wayne Estes Center, which opened in 2014, serves as a practice venue for USU men’s and women’s basketball teams, and the women’s volleyball team (no men’s V-ball due to Title 9) plays its matches there. Finally, he was inducted into the Utah Sports Hall of Fame in 2015. Why so late? One of the Hall’s rules stipulated that a person had to have been born in Utah or lived there for at least 10 years. It was belatedly waived for Estes.

The greatest of USU basketball players was born nearly 80 years ago. While A.E. Housman’s classic set of poems A Shropshire Lad (an elegy about an athlete dying young) was published in 1896, it could have been intended for Estes.

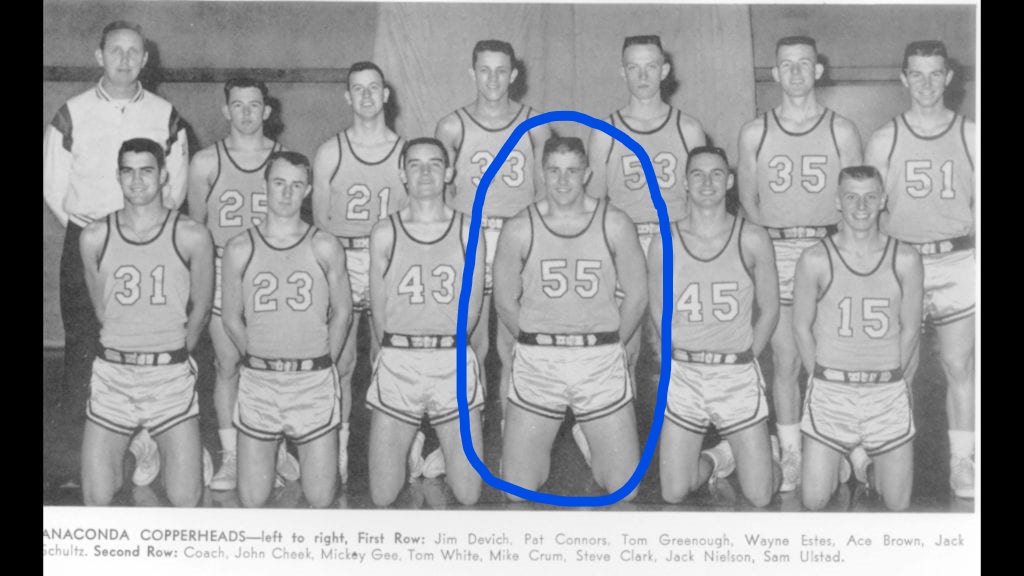

Wayne Estes and Anaconda High School basketball teammates in 1961.

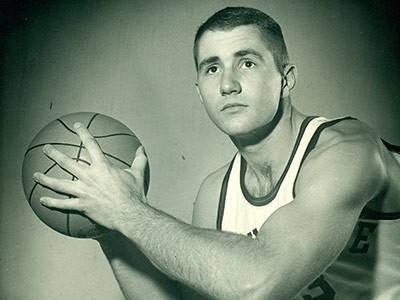

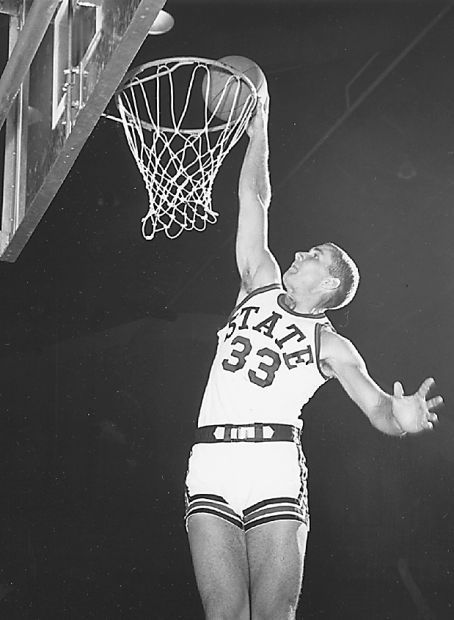

Estes at USU.

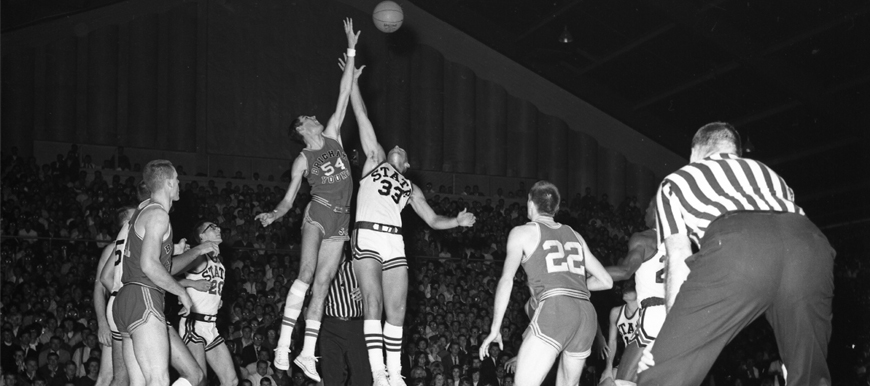

Estes in action against Brigham Young.

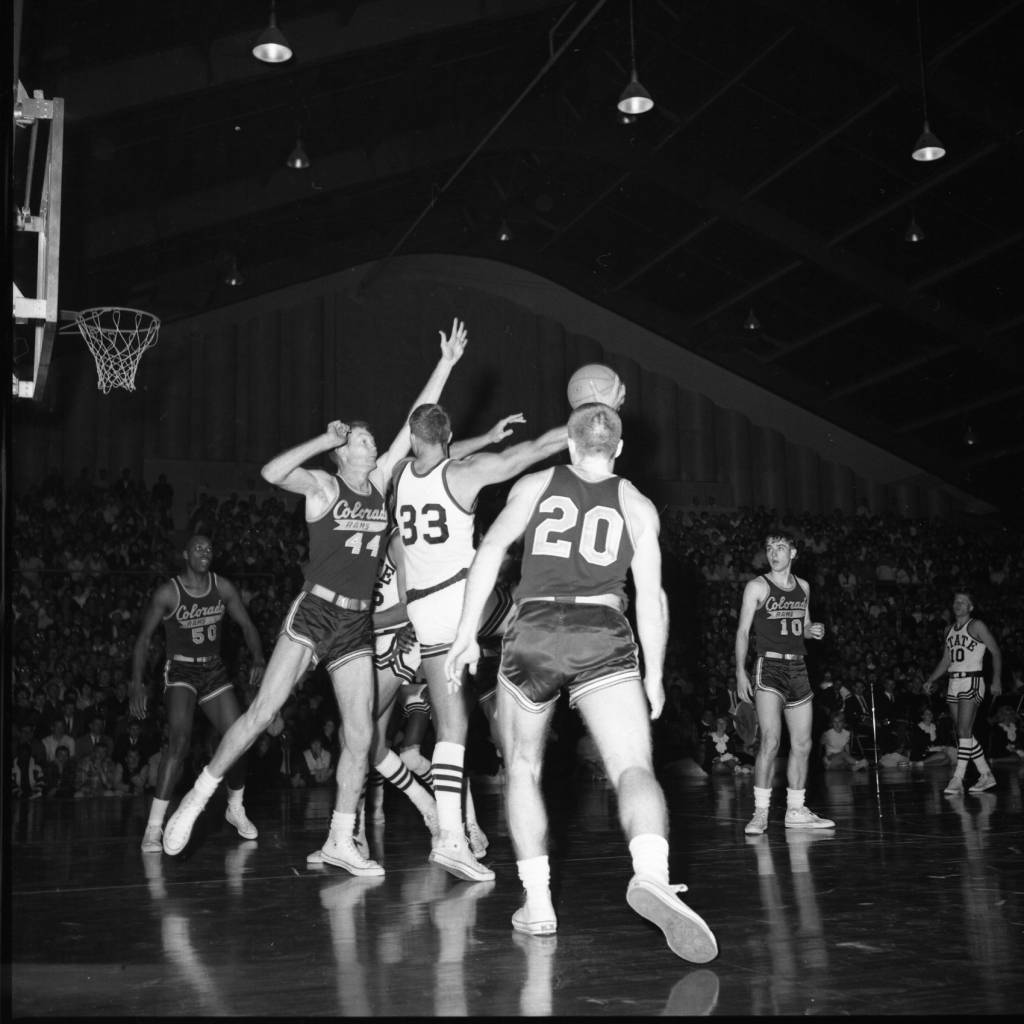

Estes in action against Colorado State.

A sleek Estes during practice at Utah State.

Estes throws down a slammer-jammer.

The car wreck that Estes and friends went to inspect and which led to his tragic death.

Estes’ death certificate–sad, sad, sad.

10 Comments

Mentioned in the same breaths as Rick Barry, Cazzie Russell, Bill Bradley, and Gail Goodrich puts Mr. Estes in a pantheon of stars from the mid-60s. A great young cager and an even better man: what more meaningful words could be spoken about an athlete? I was a teen when Mr. Estes met his Maker and well remember the impact that his death made on my adolescent mind. Had thought that big, strong, young men don’t die young. Today’s stars of sport would do well to read about Mr. Estes’ deeds AND mortality.

An essay worthy of A. E. Housman, RAP, as this is one of your best.

Let the record show that I borrowed (with your permission) the Housman reference.

as always richard very interesting thank you for the writings!

Well, thank you for reading it, Billy

So sad but interesting article as always.

Thank you, Jake!

I just got back into my facebook after being locked out for a long long time. Really great article!

Thanks, Kenny. I had not heard of Wayne Estes until a friend informed me a month ago.

Wayne Estes was a hero in my hometown of Anaconda, MT. His legacy lives on.

Thank you, Lisa Marie.

Add Comment