Has professional basketball ever seen a more foolish move than when Michael Jordan said toodle-oo to his Chicago Bulls teammates after three straight NBA championships so he could play baseball—rather badly—with the Birmingham Barons? That experiment on the diamond devoured all of the 1994 season and most of 1995 before Jordan admitted the obvious and returned to hoops; the Bulls proceeded to win the next three titles.

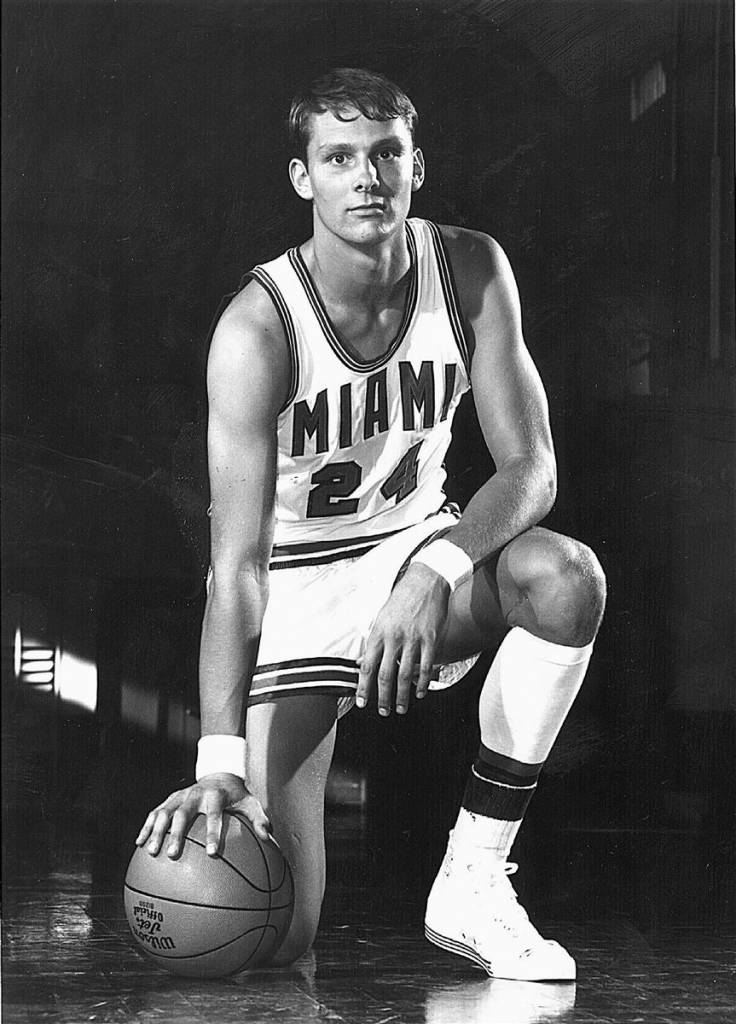

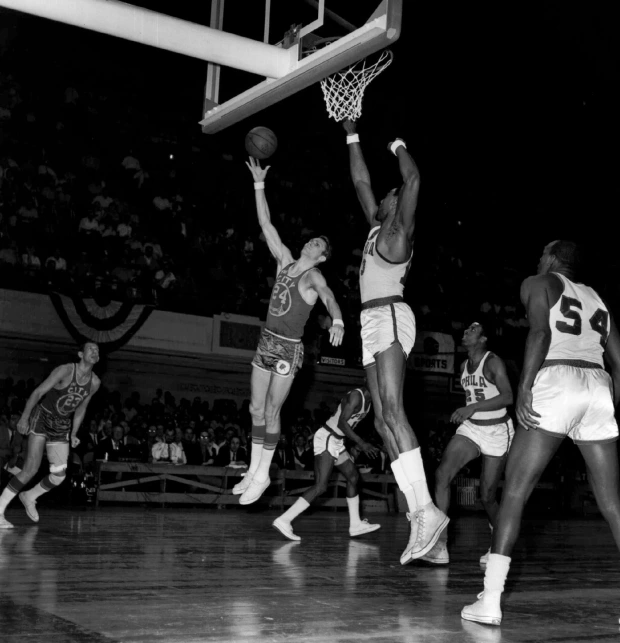

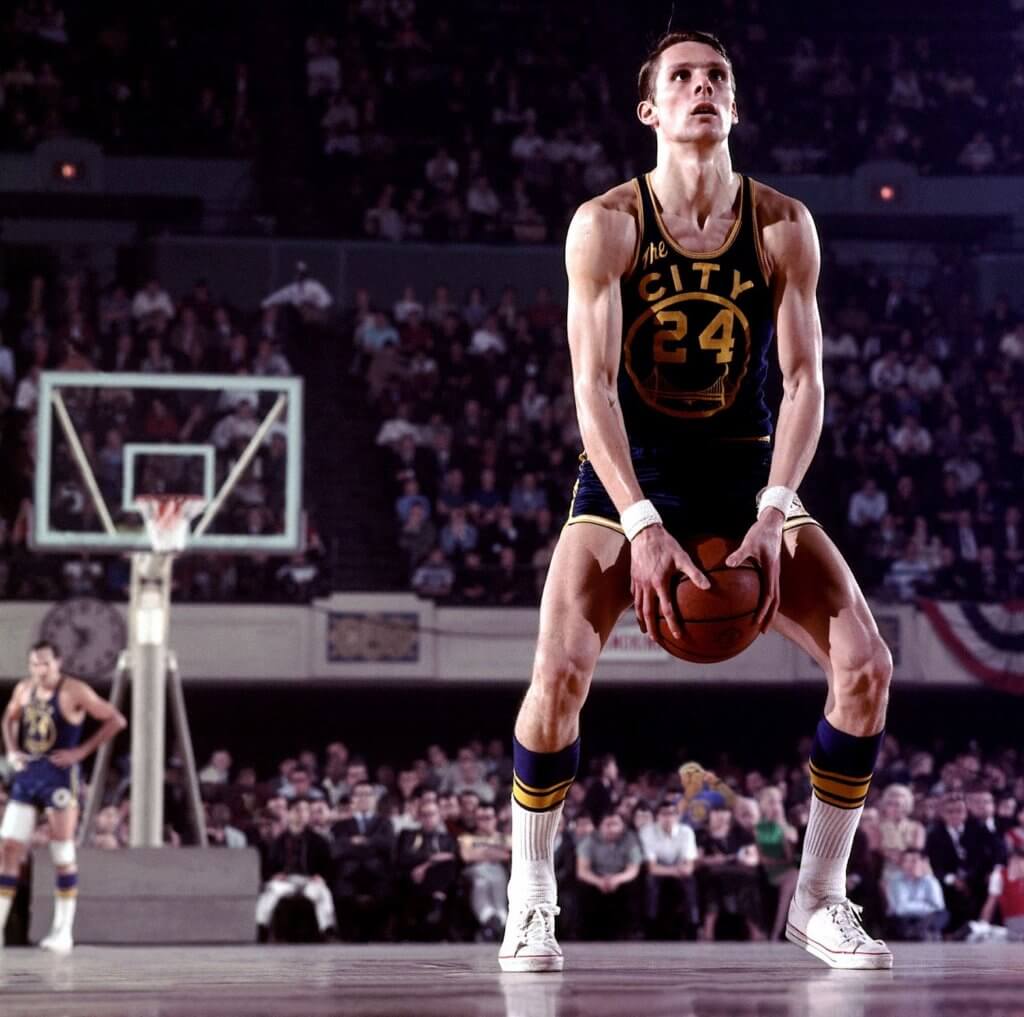

I can think of one, and the idiot was Rick Barry. The second overall pick, out of the University of Miami, in the 1965 NBA draft by the San Francisco Warriors, he proceeded to set the league on fire. This sleek 6′ 7″ forward was rookie of the year in 1966 (25 points and 10 rebounds per game) and even better the next season—36 and 9, and MVP of the All-Star Game. Barry, center Nate Thurmond and guard Jeff Mullins enabled the Warriors to take Wilt Chamberlain’s great Philadelphia 76ers team to six games in the 1967 finals. Despite a nagging knee injury, he averaged 41 points per game and won plaudits from Chamberlain: “The guy was so good that we had to have three different guys guard him at different times because he would run them all ragged.” His coach, Bill Sharman, concurred. “This far in his career, I would have to rank Rick as the greatest and most productive offensive forward ever,” he said.

(Background information on Barry is as follows. This New Jersey native learned the game from his father. Lightly recruited, he ended up at Miami, a school without much basketball history. Barry scored 19 points per game as a sophomore, 32 as a junior and 37 as a senior. The Hurricanes’ coach was Bruce Hale, whose daughter Pam caught Barry’s eye. They married and started having kids, four of whom—Brent, Jon, Drew and Scooter—would later enjoy substantial college and pro careers, although falling far short of their illustrious father. [Another son, Canyon, can be added to that list, but he had a different mother, Lynn; Barry and Pam went through a contentious divorce in 1979.])

Barry could do it all. Despite ringing the bell for so many points, he was no ball hog. He was a superb passer who kept his teammates involved, ran the fast break, rebounded, had a good handle, played crafty defense and shot under-handed free throws at an 89.3% clip. He could go to the rim or shoot from the outside with aplomb. A fiery, driven player with plenty of attitude, Barry was hypercompetitive. His only concern was winning.

That being the case, one may fairly ask why Barry jilted the Warriors soon after they nearly became the 1967 NBA champs. Although he had a valid contract with San Fran, he signed another with the Oakland Oaks of the start-up American Basketball Association. When owner Franklin Mieuli failed to pay agreed-upon bonuses, Barry felt that his worth to the team was insufficiently recognized. He grumbled about Sharman, although I cannot see why; Sharman had all the bonafides as a player (four titles with the Boston Celtics) and coach (he had led the Cleveland Pipers to the 1962 ABL championship and would repeat the trick with the Utah Stars of the ABA in 1971 and the Los Angeles Lakers of the senior league the next year), and as we have seen, he held Barry in high regard. With the Warriors doing so splendidly in 1966 and 1967, they had a vibrant future with him as the key. The Oaks offered him a five-year contract at $75,000 per—considered big money at the time—and part ownership of the franchise, but the main reason was that he would be playing under Bruce Hale, his father-in-law and collegiate coach.

The Warriors went to court and prevailed, so Barry was barred from playing in 1968. Unbelievable! A guy in his third year as a pro, who was riding the wave like few others before or since, voluntarily sat out an entire season. Barry helped with radio broadcasts for the Oaks, who went a miserable 22-56. Hale was fired, so the bold Rick-and-Bruce plan fizzled. He must have wondered what he had gotten himself into.

Let me pause here and say that I was and remain an ABA fan. I attended many of the Dallas Chaparrals’ games at Memorial Auditorium and Moody Coliseum (including one in which Barry tangled with Cincy Powell, both being sent to the showers). I loved the red-white-and-blue ball, the three-point shot and the new league’s free-wheeling ways. But I cannot deny that the quality of play was below that of the NBA, and the same could be said of the arenas. Media attention reflected those facts. The underfunded ABA was, especially in those early years, bush-league.

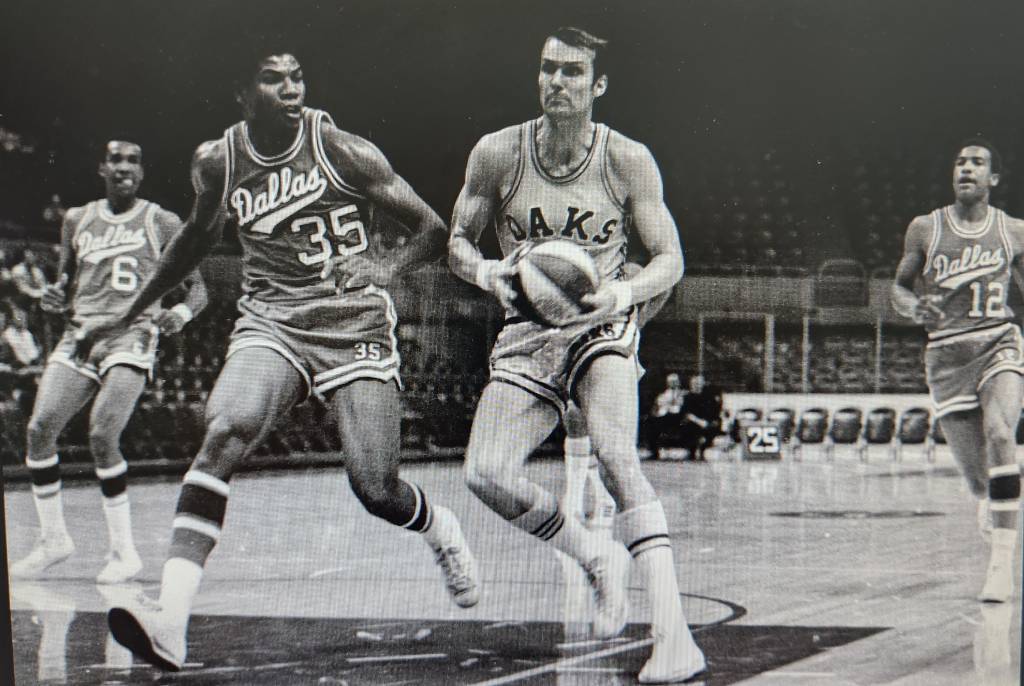

Barry, who lost five seasons from the heart of his NBA career—he sat out one and played four—nonetheless was the ABA’s savior. He brought credibility, and he brought fans out like nobody else. Let’s recall what he did those four years. The 1969 Oaks, coached by Alex Hannum, went 60-18, and then beat the Denver Rockets, New Orleans Bucs and Indiana Pacers to win the title. Barry, who suffered a knee injury in the middle of the season, played in just 35 regular-season games but averaged 34 points per game.

Home attendance at Oaks games was poor, so the franchise was sold, moved across the country and renamed the Washington Capitals. Barry was not enthused: “If I wanted to go to Washington, I’d run for president.” The Caps, for some strange reason, were part of the ABA’s Western Division, which meant a lot of traveling. Barry, due to his recalcitrance and knee problems, appeared in only 52 regular-season games. Still quite brilliant, he scored 27 points per game. Washington lost a seven-game playoff series to Denver; Barry went down fighting with 52 in that last game.

The team was about to become the Virginia Squires—and sign a forward from the University of Massachusetts named Julius Erving. But Barry had seen enough and wanted out. He was traded for cash and a No. 1 draft pick to the New York Nets, for whom he played the next two years. (Erving would follow Barry there, too, in time.) His high-scoring ways continued. The 1972 season was a thrilling one in which he led a late charge that nearly secured another ABA title. The Nets beat the Kentucky Colonels and the Squires before losing to the Pacers in the finals. Our man averaged 33 points per game throughout the playoffs.

New York coach Lou Carnesecca had this to say about Barry: “He was a great artist. A Mozart. A Picasso. A Caruso. I’d diagram a play, and Rick would instinctively see four or five options that I’d never even imagined. In 35 years of coaching, I’ve never had another guy like that.” The Nets did not have big and plush Madison Square Garden as their home, not at all. They played in gyms in Long Island and New Jersey, far from Manhattan. Barry’s teammates razzed him by calling him “Hackensack Rick” in contrast to the New York Jets’ “Broadway Joe” Namath.

In the summer of 1972, a U.S. district court judge issued an injunction prohibiting Barry from playing for any team besides the renamed Golden State Warriors (with whom he had re-signed in 1969), so he was headed back “home.” There was some resentment against him among players, coaches, media people and fans since he had abandoned the NBA for five years, but he was unconcerned. The other Warriors soon elected him captain, and he was truly their leader. Barry, who had put on another 20 pounds of muscle, reached his professional peak in the 1975 season when he averaged 31 points per game and carried them through the playoffs, triumphing over the Seattle SuperSonics and the Bulls before sweeping the heavily favored Washington Bullets in the finals. It was a vintage performance. I recall watching those last games at the Posse East in Austin and feeling nothing but admiration for Golden State’s splendid forward.

The twilight of Barry’s career consisted of two seasons with the Houston Rockets. A free agent then, he had contract talks with Boston, Seattle and the New York Knicks, but nothing resulted from them and he retired. Barry had taken part in 1,020 pro contests, being on the court an average of 37 minutes per game. His numbers speak for themselves: 25,279 points, 6,863 rebounds, 4,952 assists and 1,104 steals. A perennial all-star, he won a championship in each league and reached the finals two more times—once in the NBA and once in the ABA.

Earlier, I alluded briefly to how Barry often antagonized people. He whined about every call that did not go his way, employing eye rolls, facial expressions and body language that conveyed his displeasure. So refs did not like him. Nor did most opponents, nor did most teammates. NBA long-timer Mike Dunleavy said this of Barry: “He lacks diplomacy. If they sent him to the UN, he’d end up starting World War III.” Former Nets teammate Billy Paultz opined, “Around the league they thought of him as the most arrogant guy ever. Half the players disliked Rick. The other half hated him.” Dunleavy and Paultz were engaging in obvious hyperbole. For some perspective, consider this line from Warriors teammate Clifford Ray: “Rick may not be the kind of guy to say, ‘please,’ but he’s in it to win.”

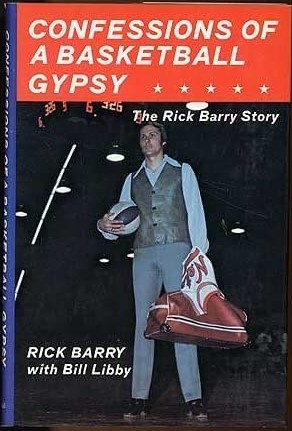

Barry, whose ghostwritten autobiography was entitled Confessions of a Basketball Gypsy (I read it), lives today in Colorado Springs. He has come to realize that he was his own worst enemy and that he is not loved like other White basketball greats from that era, such as Jerry West, John Havlicek or Pete Maravich. Never has he had an NBA coaching job, so he spent a few years coaching teams in the boonies. “I acted like a jerk,” he acknowledged. “Did a lot of stupid things. Opened my big mouth and said a lot of things that upset and hurt people. I was an easy person to hate. I tell my own kids, ‘Do as I say, not as I did.’”

Barry hooks over Chamberlain in 1967 NBA finals…

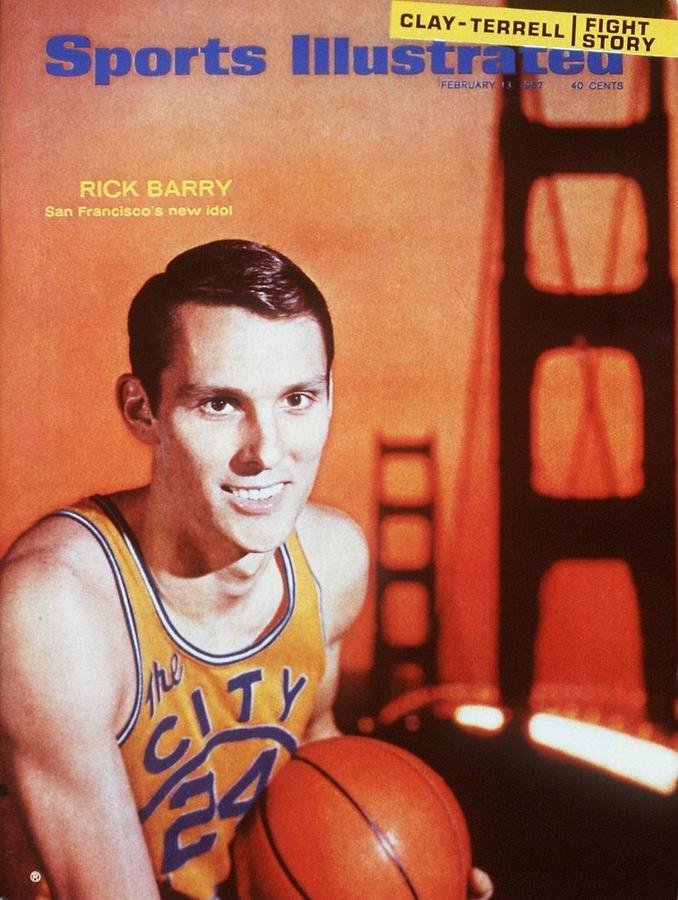

One of four SI covers devoted primarily to Rick Barry…

5 Comments

vintage Pennington

what baby boomer basketball fan does not know the name Rick Barry?

who among them did not try shooting underhand free throws?

The rest is news to me wonderfully researched, lived and delivered.

Thank you, Tom in Copenhagen! How I wish I could visit you there.

What scares me, RAP, is that few who aren’t Baby Boomers know a lick about who Rick is and what he did on the court. Sure, he was a whiner but his greatness far overshadowed that. Unlike a lot of young guys who came into big money, however, finally settled down. When he gets to the Promised Court, Pistol will be there waiting for HORSE three-point bombs, or free throw flips.

Thanks, Richard, as you always come through with the right words, solid sentences, and pithy thoughts.

You saw him at Chicago Stadium…you know how studly Barry was. In light of Carnesecca’s comment, it’s too bad he wasn’t able to coach. But always, that grating personality worked against him. I left out the fact that he was a CBS broadcaster in the early 1980s but got canned because colleagues and viewers/listeners didn’t like him.

DISREGARD MY EARLIER, SLOPPY COMMENTS.

What scares me, RAP, is that few who aren’t Baby Boomers know a lick about Rick and what he did on the courtS. Sure, he was a whiner but his greatness far overshadowed that. Unlike a lot of young guys who came into big money, however, he finally settled down. When he gets to the Promised Court, Pistol will be there waiting for HORSE, three-point bombs, or free throw flips.

Thanks, Richard, as you always come through with the right words, solid sentences, and pithy thoughts.

Add Comment