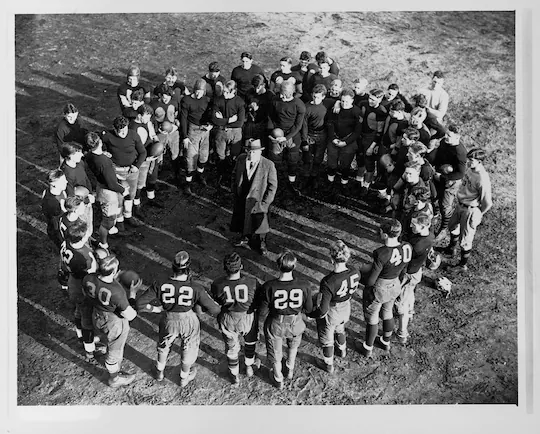

In the early part of the 20th century, the University of Chicago was a major force in college football. Coach Amos Alonzo Stagg’s Maroons won 244 games including two national championships (1905 and 1913) and seven Western Conference—later renamed the Big Ten—titles. Three of his more notable players were Hugo Bezdek, Fritz Crisler and Jesse Harper. Playing in 50,000-seat Stagg Stadium, they were the original monsters of the Midway. And if Chicago boosters slipped his guys a little money after a big victory, or if fraternity brothers wrote their papers for them, or if professors cut them some slack, or if local sports writers lionized them, so what? The same thing was done in Ann Arbor, Columbus, Minneapolis and other Big Ten towns.

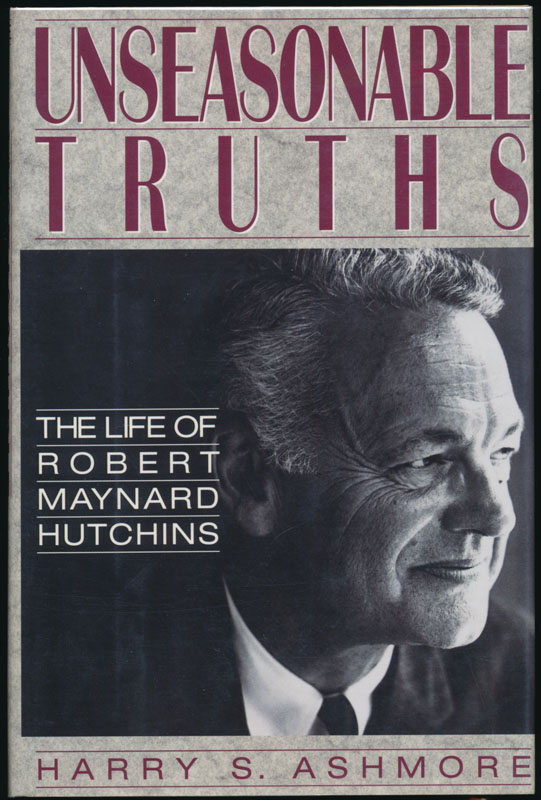

Stagg may not have known it, but when Robert Maynard Hutchins became UC president in 1929 he had met his match. The Maroons went 7-3 that year and would never again have a winning record under Stagg or the man who followed him, Clark Shaughnessy. Hutchins, equipped with two degrees from Yale University, lost no time in implementing wide-ranging reforms at the school John D. Rockefeller had founded in 1890. They included interdisciplinary programs, a pedagogical system based on the great books and Socratic dialogue, and an overarching philosophy he labeled “secular perennialism.” Hutchins’ plans were not limited to academics, since he had made up his mind to get rid of football. In a 1954 article in Sports Illustrated, he paraphrased writer and philosopher Elbert Hubbard: “Football is to education what bullfighting is to agriculture.”

Hutchins put the football program under increasingly narrow confines, which helps explain why UC was so bad those last few seasons. Shaughnessy’s 1939 team was outscored 192-0 in Big Ten play. The student body had been changing for several years, and football had apparently lost its charm. The Board of Trustees voted 32-0 in support of Hutchins’ plan, which he announced in an address entitled “Football and College Life” to UC students at Mandel Hall on January 12, 1940. This man had both supporters and critics. Among the latter was Jay Berwanger, Chicago’s 1935 Heisman Trophy winner. The Maroons did indeed stop fielding a football team (although it would be resurrected as a club sport in 1963 and move up to Division III six years later). The immediate effect was a decline in enrollment and alumni donations, but the University of Chicago bounced back and retained its status among the top schools in the country. That has not changed; US News & World Report currently ranks it sixth. UC has an $11.6 billion endowment and can point to 94 Nobel Prize laureates, 53 Rhodes scholars, 27 Pulitzer Prize winners and 29 billionaire alumni. Chicago is a fine school, no doubt about it.

Whether or not he was an ivory-tower idealist, Hutchins boldly cut football at UC. Schools that continued to sponsor these semi-professional teams, he suggested, resembled kindergartens and country clubs. Hutchins was not alone in decrying the troubling rah-rah, sis-boom-bah football trend. After all, the Carnegie Report had been issued in 1929, followed by the formation of the Ivy League (no athletic scholarships, no spring training, no bowl games) in 1945, the NCAA’s Sanity Code in 1948 and reports by the Knight Commission in 1991, 2001, 2010 and 2020. All well-intended, these had a minimal impact on King Football. Michigan State took Chicago’s place in the Big Ten, and the game just kept rolling along—seemingly bigger and more prosperous every year.

Other schools that have dropped football, for a multiplicity of reasons, include Providence College (1941), Marquette University (1960), the University of Detroit (1964), the University of San Francisco (1971), Wichita State University (1986), Boston University (1997) and the University of Alabama-Birmingham (2015, although play resumed two years later). None, however, were as dramatic as what happened at UC.

Hutchins may have believed things were intolerable then, but they have gotten far worse in the ensuing 82 years. The student-athlete has become the athlete-student, many players at top schools can barely read or articulate a sentence in English, they are notorious for committing sexual violence against female students, coaches are paid astronomically (the University of Georgia’s Kirby Smart recently signed a 10-year, $112.5 million contract extension), and the stadiums are on a much larger scale. Hutchins could never have imagined today’s intense media focus, NIL and the transfer portal, whereby players insouciantly jump from one school to another. A college football gambling scandal is bound to happen soon—you can bet on it. Lip service is now seldom paid to the quaint notion of football players benefiting from higher education.

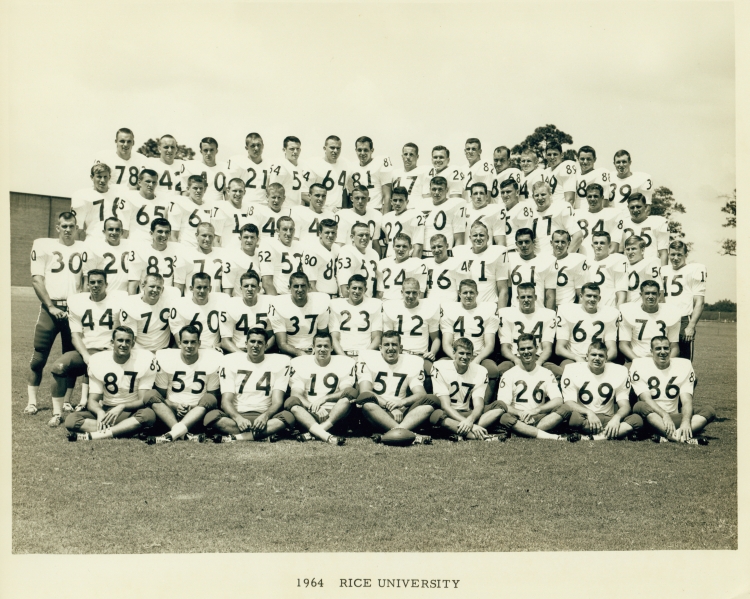

Let us now turn to another institution for academe, one situated 940 miles to the southwest. Rice University, founded in 1912 on a 300-acre campus on Houston’s South Main Street, was a charter member of the Southwest Conference. Despite representing a small private school with high scholastic standards, the Owls won conference titles in 1934, 1937, 1946, 1949, 1953 and 1957. I will list a few of the great players who have worn blue and gray: Bill Wallace, Weldon Humble, Tobin Rote, Dicky Maegle, Buddy Dial, Tommy Kramer and Trevor Cobb. Rice Stadium (seating capacity of 70,000) opened in 1950, ten years before the Houston Oilers of the American Football League started play. By then, the glory days were mostly over. When the SWC folded after the 1995 season, Rice was not invited to join the Big 12. The Owls have since been affiliated with a couple of minor leagues, Conference USA and the American Athletic Conference. No longer playing against schools with which they shared decades of history and organic relationships—Texas, Texas A&M, Baylor, TCU and so forth—they now face opponents such as Louisiana Tech, Western Kentucky, Charlotte and McNeese State. Paid attendance at home games hovers around 15,000, aided by occasional visits from former SWC foes. (They come for the sake of their own alumni and to aid recruiting in fertile metro Houston.) Even then, the Owls sometimes suffer the indignity of hosting games at NRG Stadium, home of the Houston Texans; Rice Stadium is dilapidated, with seating capacity now listed as 47,000.

I have been on the tree-shaded Rice campus once, to witness the 1992 Texas-Rice game. I passed by it each of the 10 times I ran in the Houston Marathon. Furthermore, I have two friends who attended that school. When Rice alums call it the Harvard of the Southwest, they have good reason to boast. With a 6-to-1 student-faculty ratio, it is ranked seventeenth by US News & World Report. Getting into Rice is hard and graduating from Rice is also hard. You can’t be a dummy and go to Rice.

But there are problems galore on South Main. The last time the Owls had a winning record in football was 2014. Home attendance is poor, media attention is scant, the stadium is falling apart, few students have enthusiasm for the game, and the athletic department loses about $10 million every year. The Rice Faculty Council has complained about the school’s jockocracy; football players have a 2.7 GPA, well below the 3.3 for other male students, and even that is deceiving since they take easier courses and have “academic advisors.” The faculty, and more than a few alumni, have asked many of the same questions Robert Maynard Hutchins used to ask at the University of Chicago: How does a football team, regardless of its won-loss record, contribute to an academic institution? Should athletics be at the heart of campus culture? If football players refuse to matriculate at a school without inducements and do not follow the standard curriculum, do they really belong?

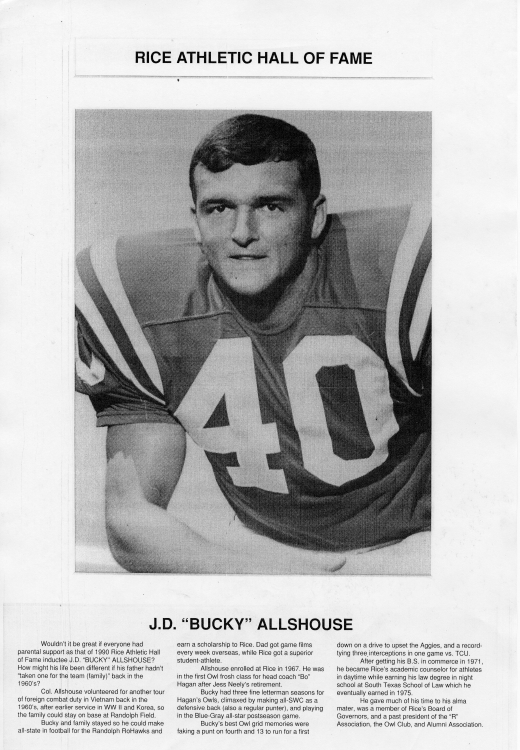

Matters came to a head at Rice in 2003. The athletic department was running big annual deficits mostly due to football, although basketball and baseball (the Owls won the national championship that year, interestingly enough) also bled red ink. At the urging of the faculty, the Board of Trustees hired a consulting firm, McKinsey & Co., to conduct a thorough analysis. Their 121-page report painted a bleak picture. But that set off a fierce and immediate reaction, led primarily by Bobby May and Bucky Allshouse. May had been a star hurdler in the mid-1960s, coached the track team from 1976 to 1979 and then served as the school’s athletic director for 17 years. Allshouse played football for the Owls in the late 1960s and became a successful attorney. Nobody should be surprised that men such as May and Allshouse cherished their experiences as Rice athletes and were not inclined to see the school drop to a lower division or eliminate intercollegiate sports altogether. Meetings were held, rallies organized, egghead professors demonized, plans made, arms twisted and funds raised. An advocacy group called Friends of Rice Athletics was formed and began a letter-writing campaign. The Board of Trustees, fearful of what Rice would be without (somewhat) big-time football and 13 other varsity sports, were convinced. They overruled the faculty and McKinsey & Co. Rice’s deal with the devil made more than a century ago, wherein sports and higher education were entangled, would remain.

Joe Karlgaard has been the Rice athletic director since 2013. The department he runs is losing money, and there is no denying that. The attitude of the faculty has probably not changed. Yes, the school has spent $54 million on facility upgrades and new construction projects in the last seven years. But that, frankly speaking, is peanuts in today’s college sports landscape. For examples, look no further than College Station and Austin; the Aggies invested $483 million on a re-do of Kyle Field, and the Longhorns’ new hoops arena came in at $375 million.

In July 2021, UT and the University of Oklahoma announced that they would depart from the Big 12 and join the Southeastern Conference, and a year later UCLA and the University of Southern California said they were leaving the Pac-12 for the Big Ten. Such moves can be boiled down to two issues—money and power. Hutchins, who died in 1977, would remind us that education and the advancement of knowledge are not part of this picture.

Rice, a proud and distinguished school, is more and more among the sports have-nots. Perhaps it should take the present opportunity to make a statement of its own, a statement of academic integrity. I realize that bowing out of the intercollegiate sports scene and razing old Rice Stadium would be painful. President Reginald DesRoches has only been on the job for a few weeks, so he lacks the power to effectuate that. Whether he has the desire, I do not know. I sent him an e-mail asking for his views earlier this week and got a no-comment answer from his secretary.

DesRoches, a native of Haiti, must be aware that eliminating football and basketball at Rice (heavily black, as is the case at almost every other school) would fly in the face of the current drive for “equity” and “diversity.” In this regard, the task facing Hutchins in the 1930s was far easier since all of Stagg’s players were White. DesRoches evidently has no choice but to support the status quo at Rice. Nevertheless, the time may come when the plug has to be pulled, and it won’t be for the high-minded reasons put forth by Hutchins.

5 Comments

Interesting article about football. This sport was appreciated and loved by young people and not only that, I still see the stadium full of supporters, even if now football is still what it once was. The big clubs have made a business out of it, and this sport he lost from success another time.

Your article is very good like the others, you did a good job.

Thank you for your articles on various topics, they are interesting, I am waiting for a new one.

Thank you, Elly. This article entailed a lot of research, writing and re-writing!

Hutchins made the correct decision, took his lumps, and made Chicago into the academic powerhouse it is to this day. In “It’s a Wonderful Life”, Lionel Barrymore made reference to “Sentimental hogwash.” From what Mr. Pennington has written about Rice, this same spirit is pervading and preventing the great institution from dismantling their crumbling and expensive athletic program. Some Midwestern advice? Downgrade sports to Division III, eliminate athletic scholarships, demolish the stadium and build a modest, smaller venue, and create a museum that will preserve the glories of yore, If I were a betting man, however, I’d hedge my wager that the “permanently pusillanimous” will prevail and the red ink will continue.

What Hutchins did was mighty bold, even if it did not fully stick (academics and football). As for the Owls, what a conundrum they face…. I agree with you about what will probably happen.

Ok, I wrote a comment and it didn’t post. My error I’m sure. Well anyway, it was an interesting article, especially when I got to the part about Rice University. Back in the 1970s, after we had graduated, I had a friend and his dad had donated 100 acres to Rice. It was a sports article, but a good one. I don’t know who all those people were. But keep them coming.

Add Comment