If you were to somehow combine Clyde Lovellette, Danny Manning, Paul Pierce, Raef LaFrentz, Nick Collison and Mario Chalmers into one super-great University of Kansas basketball player, he would still fall short of Wilton Norman Chamberlain, Esq. Number 13—a member of the KU frosh team in 1956 and the varsity in 1957 and 1958—was it. I will leave aside his achievements at Philadelphia’s Overbrook High School (47.2 points per game and two city titles) and in the NBA (31,419 points in 14 seasons, a pair of championships in Philly and LA, and numerous titanic clashes with Boston’s Bill Russell), looking instead at Chamberlain as a collegian.

He was the subject of the first massive recruiting campaign, as more than 200 schools sought his services. Given that Philadelphia and Lawrence are separated by 1,167 miles, why did he sign a scholarship with KU in May 1955? Long-time coach F.C. “Phog” Allen had convinced some local “godfathers,” both White and black, to make him feel welcome. This was done in ways that would later cause the NCAA to conduct an investigation that led to two years of probation, by which time Chamberlain was long gone. His father (a janitor by trade) got a better job, he always drove a shiny new car, and he had abundant walking-around money.

Then again, why not Kansas? The game’s originator, Dr. James Naismith, had been on the faculty and coached there. Allen and Adolph Rupp—whose Kentucky Wildcats were then flying three national championship banners—had played at KU. The Jayhawks had won it in 1952 and were runners-up in 1940 and 1953. (Warming the KU bench in the early 1950s was Dean Smith, who would later lead North Carolina to two championships.) Furthermore, they were opening up a big new arena, Allen Fieldhouse. Lawrence, a midwestern town, was nominally integrated, and it would be much more so by the time Chamberlain left. He made it clear to Allen that he would not put up with any Jim Crow business. His coach, who had helped erect the Big 7’s gentleman’s agreement two decades earlier, understood that it was a new day; freshman games against Rice (in Houston), TCU (Fort Worth), SMU (Dallas) and LSU (Baton Rouge) were quickly canceled.

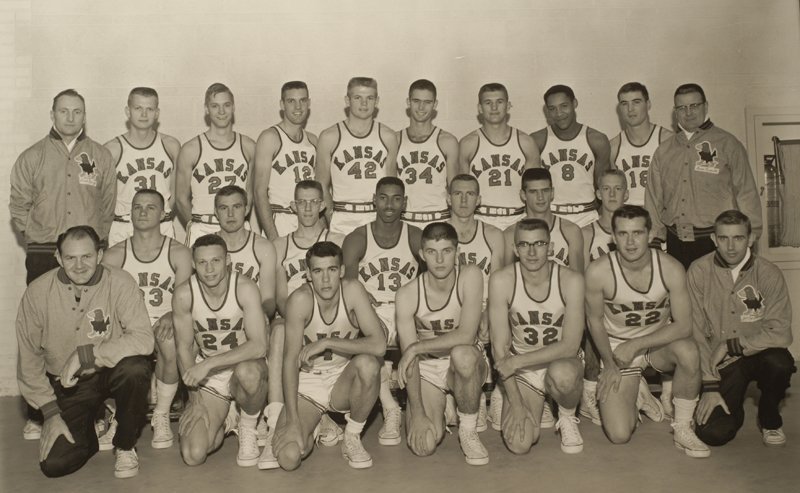

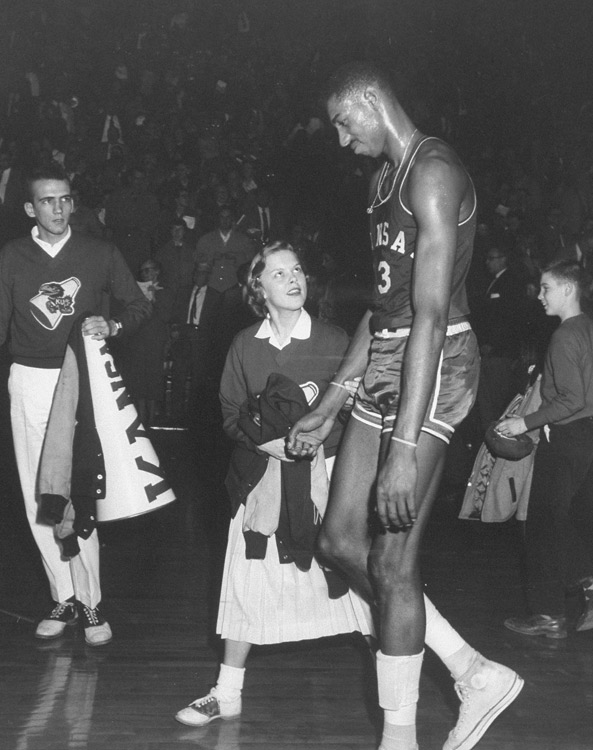

Chamberlain moved into Carruth-O’Leary Hall, met his teammates—one of whom, Maurice King, was black—and started attending classes. Obviously different, he nonetheless took part in many campus activities. He even had a job sweeping the floor at Allen Fieldhouse, although it was mostly for show. KU chancellor Franklin Murphy, athletic director Dutch Lonborg, Allen and Big 7 officials were trying to guide a potentially explosive situation.

Indicative of his expected impact on the game was a somewhat overheated article by Saturday Evening Post writer Jimmy Breslin, “Will Chamberlain Ruin College Basketball?” and the NCAA’s decisions to (1) expand the lane from six feet to twelve and (2) outlaw offensive goaltending. According to an article in The Sporting News, “He’s the greatest basketball player in the game today. Greater, perhaps, than any other who has ever lived.” A Kansas tradition since 1923 was the freshmen-varsity basketball game which took place during homecoming. The first-year guys had never won before, but there had never been a Chamberlain before. Fourteen thousand students, alumni and hoop fanatics present that day saw the 7′ 1″ center score 42 points and grab 29 rebounds in an 81-71 victory.

Allen did not seem surprised or even unhappy that his varsity Jayhawks had suffered such a mortifying loss. Wearing a Cheshire-cat grin, he quipped, “We could win the national championship with Wilt, two sorority girls and two Phi Beta Kappas.” Allen, then approaching 70, hoped that the rule mandating retirement for state employees at that age would be waived for him. I surmise that, after coaching Kansas basketball for 37 years, he had accumulated his share of enemies and that some faculty members or alumni were afraid that sports were beginning to count more than academics. The rule was enforced, and assistant (and frosh head coach) Dick Harp got the top job as Chamberlain’s sophomore season approached. I doubt that Chamberlain would have gone to KU if he had known it would turn out this way.

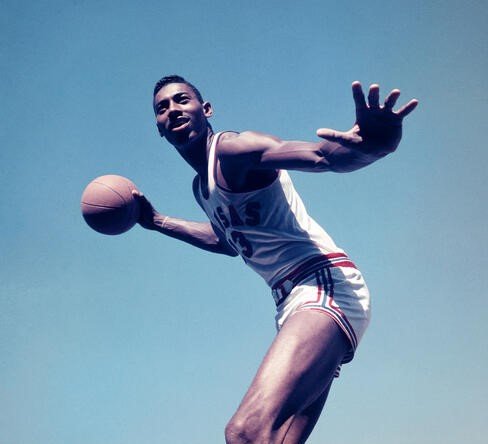

At any rate, Allen had to step aside. He must have been both pained and thrilled to witness the first game of the 1957 season, an 87-69 defeat of Northwestern. Chamberlain scored 52 points and showed an arsenal of moves against the Wildcats—acrobatic shots, finger rolls, jumpers and dunks aplenty. He also blocked shots and passed well. The dunk in those long-ago days was thought to violate an unwritten code of sportsmanship. Not to him. He had brought urban black basketball to the hinterland, and the people could just get used to it. However, I must point out that Chamberlain, bigger, stronger and far more capable than his opponents, never sought to intimidate or embarrass. After the Northwestern game, for example, he found nice things to say about the hook-shot skills of Cats center Joe Ruklick. Years later, Bill Russell would observe that Chamberlain’s biggest fault was that he lacked a mean streak.

Opposing coaches soon adjusted with stalling tactics and cheap shots. You have heard of double-teaming? Chamberlain was triple-teamed, as defenders collapsed on him as soon as he got the ball. The Jayhawks’ only two regular-season losses were on the road at Iowa State and Oklahoma A&M. Both teams stalled shamelessly; Hank Iba’s Cowboys threw 160 passes to each other before daring to take their first shot.

Kansas won the conference championship and traveled down to Dallas for the 1957 NCAA regional tournament. SMU’s new arena, soon named Moody Coliseum, was the site of two games that make Dallas natives like me cringe. To begin with, segregation was such that the Jayhawks had to stay at the Lennox Hotel in Grand Prairie, 30 miles away. The fans were brutal, waiving the Confederate flag (yes, the band played Dixie), spitting at KU players, throwing debris and pennies, and screaming racial epithets. Oh, how the mob howled! Chamberlain stayed calm and led his team to a come-from-behind 73-65 overtime victory.

Things were even worse the next night against Oklahoma City. Coach Abe Lemons did all he could to stir them up and urged his players to hack the KU center at every opportunity. It was to no avail as the Jayhawks won by 20. Chamberlain had 66 points in those two games in Dallas. Harp asked for and got a police escort to Love Field, telling the team manager to wrap things up at the Lennox Hotel.

The 1957 Final Four was at Municipal Auditorium in Kansas City, a big advantage since Lawrence sat just a few miles to the west. Harp’s team had no trouble dispatching San Francisco, winner of the last two national crowns. Then followed the game all college basketball fans wanted—North Carolina versus Kansas. The Tar Heels’ coach, Frank McGuire, was a pure-bred New Yorker, and the same for his starting lineup: four Catholics and a Jew (star forward Lennie Rosenbluth). With cigar and cigarette smoke filling the arena, the teams fought a furious triple-overtime battle with UNC coming out on top 54-53. Bitterly disappointed, Chamberlain left and walked the rainy streets of Kansas City alone. No NBA defeat ever hurt him more than this one.

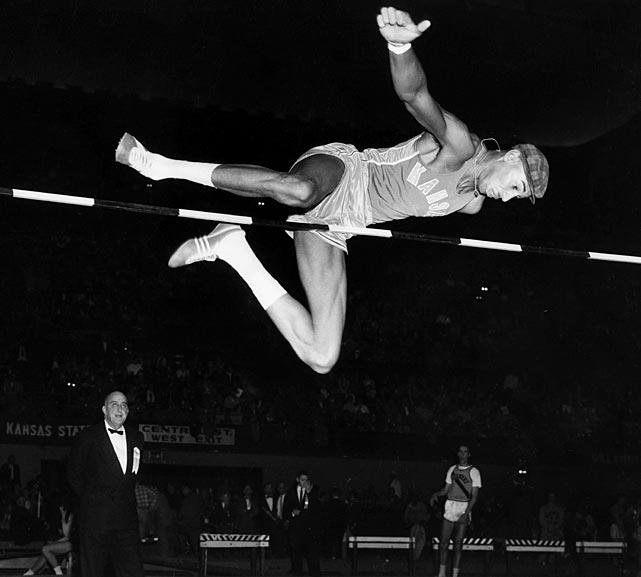

Chamberlain did not just play basketball at Kansas. He was a full-fledged member of the track team, scoring points in the sprints, the 880, the high jump and the triple jump. Always his own man, he competed in the Kansas Relays while wearing a bebop cap. He had his own rock & roll show on the KU student radio station and was involved in a number of activities that look quaint from a 21st century perspective.

Tempted to leave after one varsity season, he was convinced to stay. But the 1958 team was weaker, and his problems with Harp, an inexperienced and unimaginative coach, had worsened. The Jayhawks went 18-5, finishing second in the conference behind Kansas State. There would be no NCAA appearance for KU that year. Soon after his last game, he piled his belongings into a red Oldsmobile convertible and left town—not returning for four decades. He had written an article for Look magazine entitled “Why I Am Quitting College.” In it, he said, “the game I was forced to play at KU was not basketball.”

I can’t blame him at all. This man of amazing stamina had played virtually every minute of 48 games, of which his team won 40. Those eight losses were by a total of 28 points. Scoring 29.9 points and collecting 18.3 rebounds per game was not easy, with opponents taking full advantage of the absence of a shot clock (which remained the case until 1986) and defending him almost to the exclusion of his less-talented teammates. Had Allen been allowed to coach in the 1957 and 1958 seasons, ways would have been found to let Chamberlain flourish.

Coming on his heels were Elgin Baylor of Seattle, Oscar Robertson of Cincinnati and Lew Alcindor of UCLA. Big names all. But it was Chamberlain, this gifted athlete with the compelling persona, who presaged black ascendancy in American sports.

If bad feelings lingered between him and the school, all was forgiven on January 16, 1998. He had returned to Allen Fieldhouse, packed with 16,300 people. During a six-minute ceremony at halftime of the KU-Kansas State game, his jersey number 13 was retired. He wore his red letter jacket, and amid thunderous cheers spoke fondly of his alma mater and wept.

Chamberlain died less than two years later of a heart attack. He was 63.

4 Comments

Coaches can make or break you. Too bad for Wilt, he inherited a crummy coach. I think of Tom Landry and Dick Saban as two example of those who build a dynasty by their persona and skills as a coach.

I remember those days of college basketball before the shot clock… very boring, because the central strategy of offense was passing the ball around the outer edges…very little driving the basket… it was more of a defensive offense. Scoring was also very low, since most of the time was just passing the ball.

Yeah for the shot clock and the three point line.

So true on all your points, Gary (except that you mean “Nick” Saban and not “Dick” Saban). The game they lost at Iowa State was 39-37. One thing I somehow failed to mention in this story is that Chamberlain used to grab defensive rebounds and start dribbling downcourt…leading a fast break, sometimes going from one end to another. Visualize a 7′ 1″ guy doing that and doing it well. I saw a video of him at Kansas, and it was very different from his later NBA years when he had bulked up and lost some mobility. I tell you, at KU, he was just flat amazing.

The hidden gem in this article is future Texas coach Abe Lemons antics and following the racial lines in the 1950’s. He would change his tune by the time he hit Austin.

You noticed that, Rob! Old Abe behaved very badly in Dallas….

Add Comment