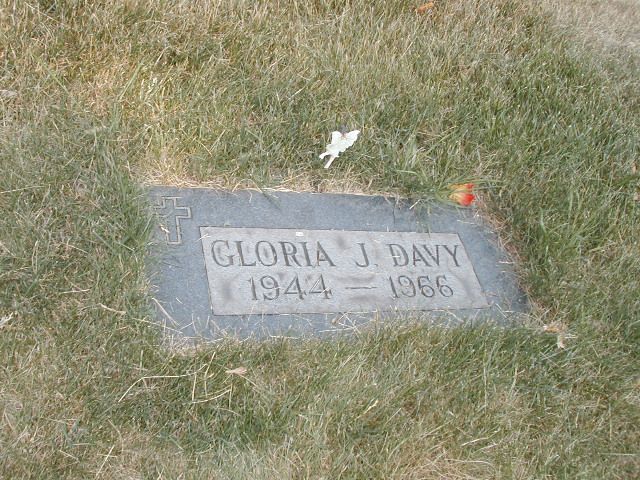

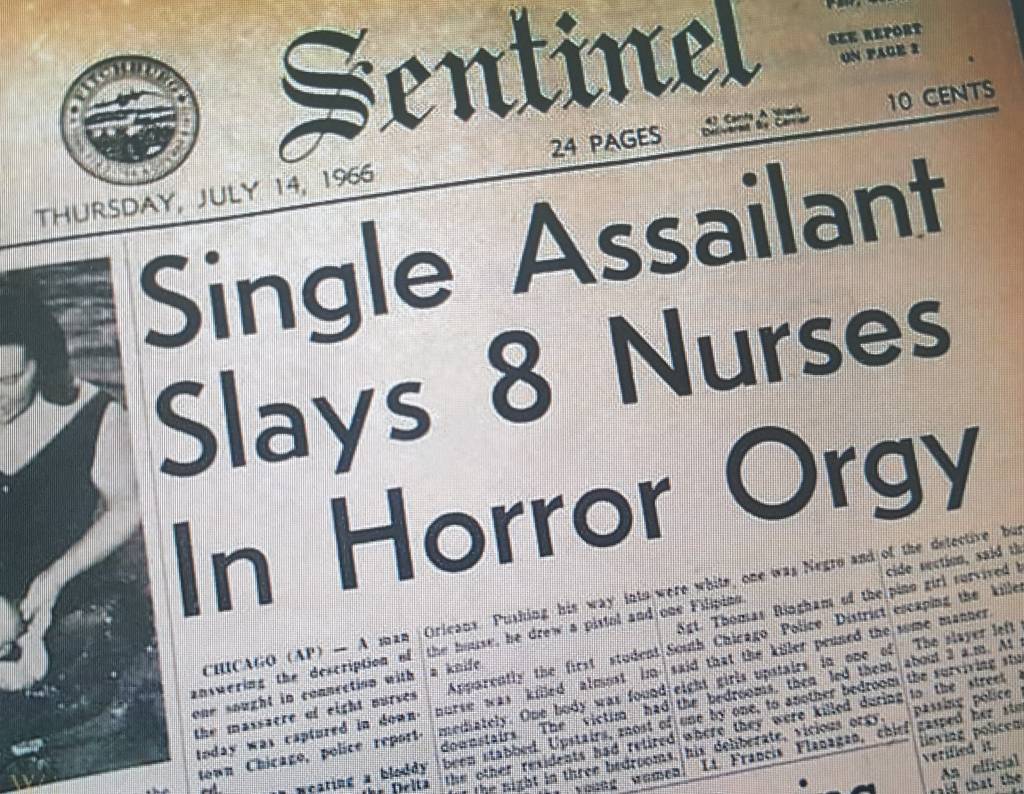

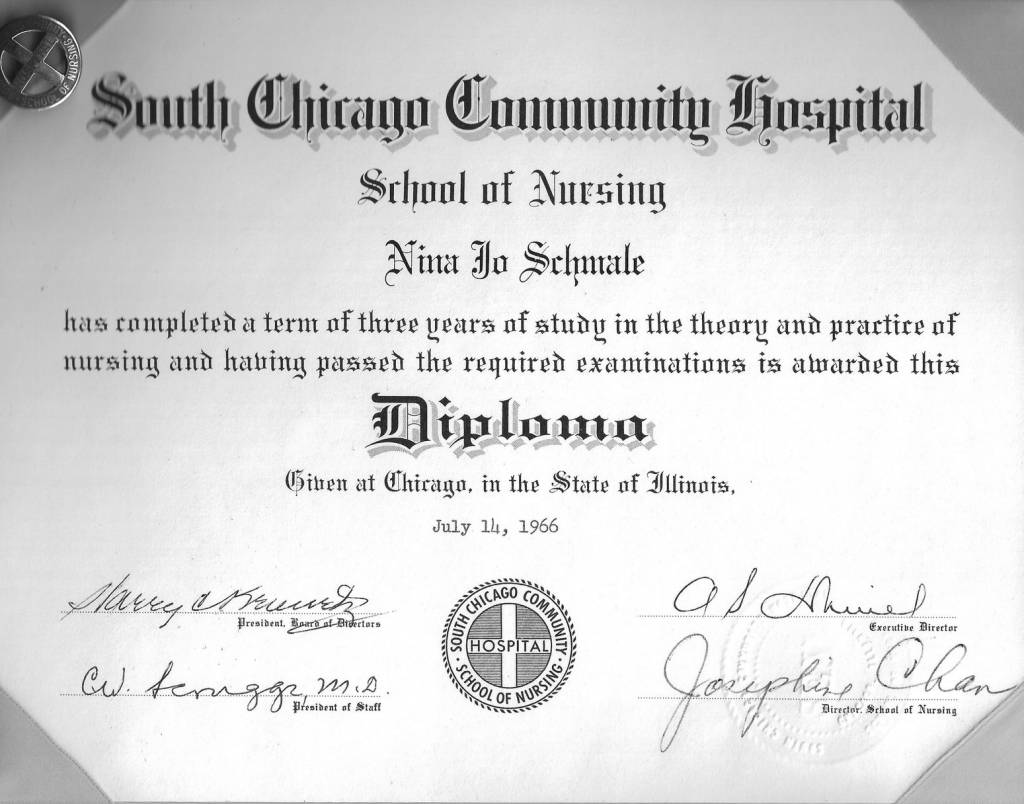

People in Chicago may have been rather hyperbolic in calling it the “crime of the century.” But what a 24-year-old, pock-marked, sociopathic drifter named Richard Speck did over five hours bridging July 13 and 14, 1966 was awful enough. Carrying a switchblade knife and a .22 caliber Rohm pistol (which he had stolen earlier in the day while raping middle-aged Ella Mae Hooper), he gained entry to a townhouse at 2319 East 100th Street in the city’s Jeffrey Manor neighborhood. It was occupied by student nurses working at nearby South Chicago Community Hospital: Gloria Jean Davy (22), Suzanne Bridgit Farris (21), Mary Ann Jordan (20), Patricia Ann Matusek (20), Nina Jo Schmale (24), Pamela Lee Wilkening (20), Merlita Ornado Gargullo (23), Valentina P. Pasion (24) and Corazon Pieza Amurao (23). The first six were Americans, and the last three were Filipinas who had come to the USA on May 9 as exchange students.

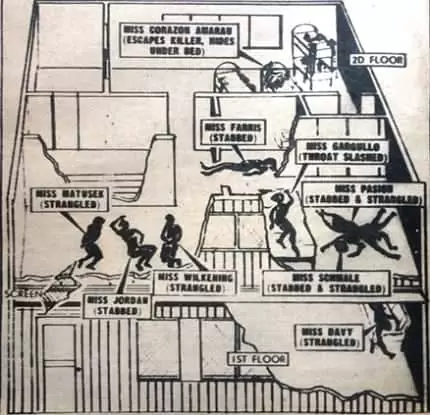

Working alone, Speck bound these terrified young women hand and foot, then began to take them one by one to different rooms with bad intent. Davy, Farris, Jordan, Matusek, Schmale, Wilkening, Gargullo and Pasion were stabbed and strangled; Davy was raped. While this nightmarish scene unfolded, Amurao—4 feet, 10 inches tall and weighing 98 pounds—managed to wriggle underneath a bed. Speck, who later claimed to have no memory of the killings, either lost count of the number of his victims or, fearing detection, was in a hurry to get out of the blood-soaked apartment.

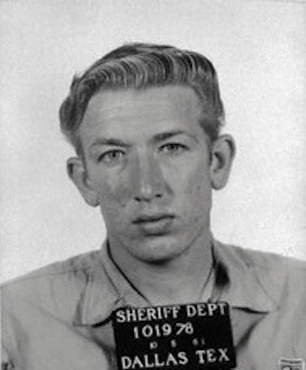

It was almost 6 a.m. when Amurao was able to untie herself and run to a balcony where she screamed for 20 minutes, “All my friends are dead! I’m the only one alive! Oh, my God! Help, please!” and other frantic words. Ambulances, police and onlookers converged en masse. As the eight dead bodies were being removed and taken to the Cook County morgue, Speck drank himself into a stupor in a skid-row hotel where rooms rented for 90 cents a night. He saw on TV and read in the Chicago Tribune that his crime had shocked the city, the state of Illinois and the entire country. I sure remember reading about it in Dallas. (Speck, I will add, had lived in my hometown for nearly a decade. He attended Long Junior High School and Crozier Tech High School, although to call him a “student” would be stretching it. Speck had been arrested 41 times in Dallas and knew about the inside of a jail cell before returning to Chicago four months before the murders.)

Following a half-hearted suicide attempt, Speck was taken to Cook County Hospital. An alert young surgical resident named LeRoy Smith noticed that “Born to Raise Hell” was tattooed on his patient’s left arm. He was aware, thanks to media reports, that the man suspected of murdering the eight student nurses had just that tattoo. Dr. Smith quietly informed authorities, and charges were soon brought.

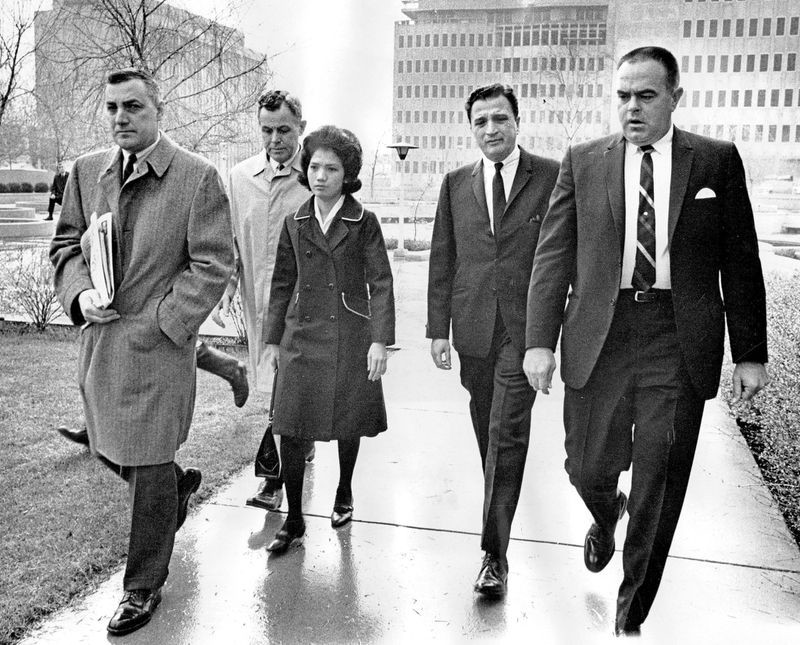

As you may surmise, the incriminating detail on Speck’s inked-up arm came from Corazon Amurao. The only surviving eyewitness to the crimes, it was she who had first opened the door when Speck knocked on the night of July 13. She made a positive identification as he lay forlornly in his hospital bed, by then held down with leather restraints. Chicago prosecutor William Martin and his assistants treated Amurao with kid gloves from the start, fearful that she might undergo a panicked response that would prevent her from testifying in Speck’s trial, which began on April 3, 1967 in downstate Peoria. Nothing of the sort would happen since this woman from San Luis, Batangas was the opposite of fragile. A bigger concern was that she would sell her story. Life magazine and the Saturday Evening Post had made substantial offers, and there was more of the same back home in the Philippines. The temptation must have been strong, but she was stronger. Amurao issued a statement which said, “It is my desire to make clear that the memory of my dear colleagues is of such character that I do not want to have it tainted by the acceptance by me of money or any other personal benefit.” (She did justifiably receive a $10,000 reward from South Chicago Community Hospital for her pivotal role in solving the case.)

Martin was confident she could handle the pressure of being on the witness stand in the Peoria County Courthouse. Certainly, the trial’s most dramatic moment came when he asked Amurao if she knew who had killed her fellow student nurses. She calmly got up, walked across the court room floor and stood in front of Speck. Her index finger almost touching his nose, she said in a firm voice, “This is the man.” Cross-examination by Speck’s court-appointed attorney, Gerald Getty, was—as it had to be—gentle, since Judge Herbert Paschen and the jurors knew what she had endured.

Martin presented other damning evidence during the 12-day trial, but Amurao’s testimony was the key. Without it, Speck might have gotten off. In fact, he might never have been charged. The jury was out just 49 minutes before finding him guilty of eight counts of first-degree murder. They recommended the death penalty, and Paschen later affirmed that and sentenced Speck to die in the electric chair. Despite Getty’s obligatory appeal, the verdict was upheld by the Illinois Supreme Court. Speck did not fry, however. He was an inmate at Stateville Correctional Center in Joliet and died there of a heart attack in 1991.

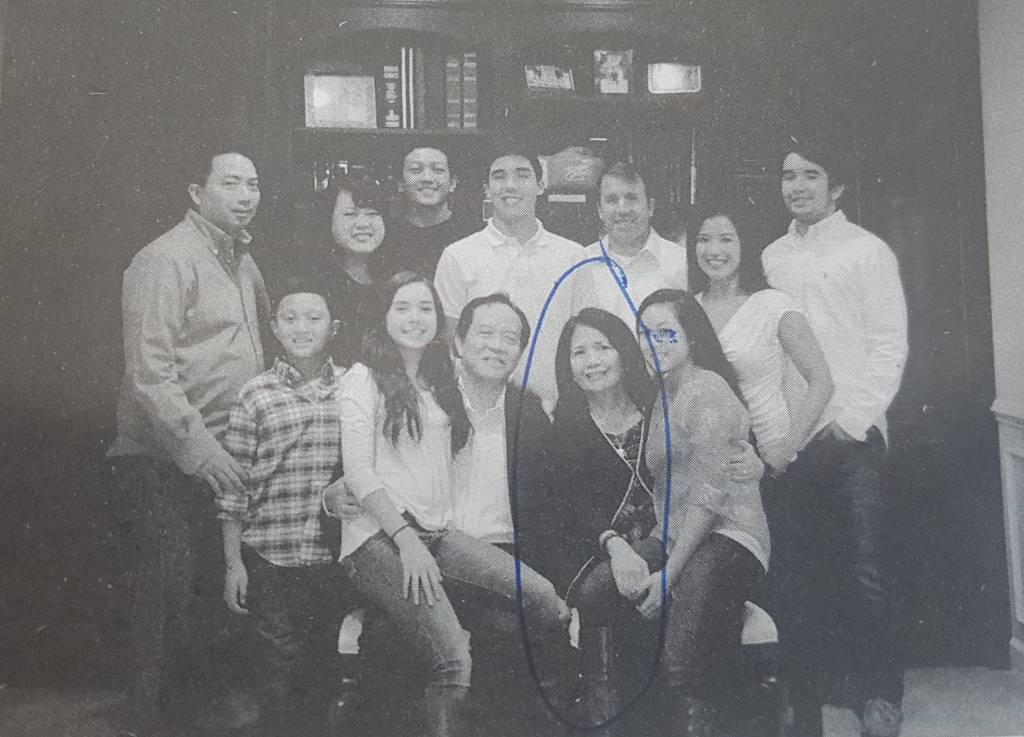

Soon after the trial, Corazon Amurao went back to the Philippines and worked as a nurse at Far Eastern University Hospital in Manila. She married an attorney, Alberto Atienza, and in 1973 they returned to the USA where she was employed at Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, DC. They had two children (and six grandchildren), later moving 20 miles south to Woodbridge, Virginia.

Amurao—now nearly 80 years old and retired—has adhered to her original policy of holding the media at arm’s length; she gives no interviews. Friends and family members say she has occasional nightmares about Speck’s nocturnal rampage in the summer of 1966. Otherwise, she has a normal and happy life. She laughs easily and sometimes visits Las Vegas to play penny-ante poker. Amurao is a shining example of heart, soul and integrity. I admire her no less than I do Aida D. Fariscal, a Manila policewoman who interrupted what could have been a large-scale terrorist attack in 1995.

Add Comment