All have passed away: President John F. Kennedy and Dallas policeman J.D. Tippit (both d. 1963), Texas Governor John Connally (d. 1993), Jesse Curry (Dallas police chief, d. 1980), Will Fritz (captain of the DPD’s homicide and robbery division, d. 1984), Bill Decker (Dallas County sheriff, d. 1970), Henry Wade (Dallas County district attorney, d. 2001), James Leavelle (detective who was handcuffed to Lee Harvey Oswald in the DPD basement when Jack Ruby plugged him, d. 2019), L.C. Graves (detective who had Oswald by the left arm and wrestled the gun away from Ruby, d. 1995), Marrion Baker (policeman who fearlessly charged into the Texas School Book Depository shortly after the shooting, d. 2011), Nick McDonald (policeman who arrested Oswald at the Texas Theatre, d. 2005), Abraham Zapruder (local dress-maker who filmed the motorcade as it passed through Dealey Plaza, d. 1970), Louis Saunders (pastor who presided over Oswald’s burial service in Fort Worth, d. 1998), James Hosty (FBI agent who interviewed Marina Oswald and irked her husband, d. 2011), J. Edgar Hoover (FBI director who decided in the first 24 hours that Oswald, and only Oswald, was guilty, d. 1972), John McCone (CIA director who withheld incendiary evidence from the Warren Commission [“the benign cover-up”], d. 1991), Earl Warren (chief justice of the Supreme Court and leader of the aforesaid commission that investigated the assassination, d. 1974), President Lyndon B. Johnson (d. 1973), Jacqueline Kennedy (the president’s widow, d. 1994), Marguerite Oswald (his mother, d. 1981), Robert Oswald (his brother, d. 2017) and John Pic (his half-brother, d. 2000). Each has gone to meet his or her maker, as have Oswald (d. 1963) and Ruby (d. 1967).

Still alive from those wrenching days in Dallas are Marina (and her two daughters, June and Rachel) and Ruth Paine, the Irving woman with whom she was living when Oswald took aim from his perch on the sixth floor of the School Book Depository. I can think of one more—Elmer L. Boyd, who worked under Curry and Fritz, and alongside Tippit, Leavelle, Graves, Baker and McDonald. He is 94 and holding his own in Blooming Grove, about 50 miles south of Dallas.

Let me pause and state my very tenuous connection to Boyd. I attended Bryan Adams High School with one of his three daughters, Pam. Not friends but merely acquaintances, we would say hi to each other before Mrs. Bronaugh’s senior English class. Only much later did I learn of her father’s role in attempting to bring Oswald to justice. Boyd spent more time with the killer—no need to qualify it with “alleged”—than anyone else after his arrest; he was present for all questioning sessions other than the final one by Fritz on Sunday morning. Boyd’s testimony before the Warren Commission took up 18 pages.

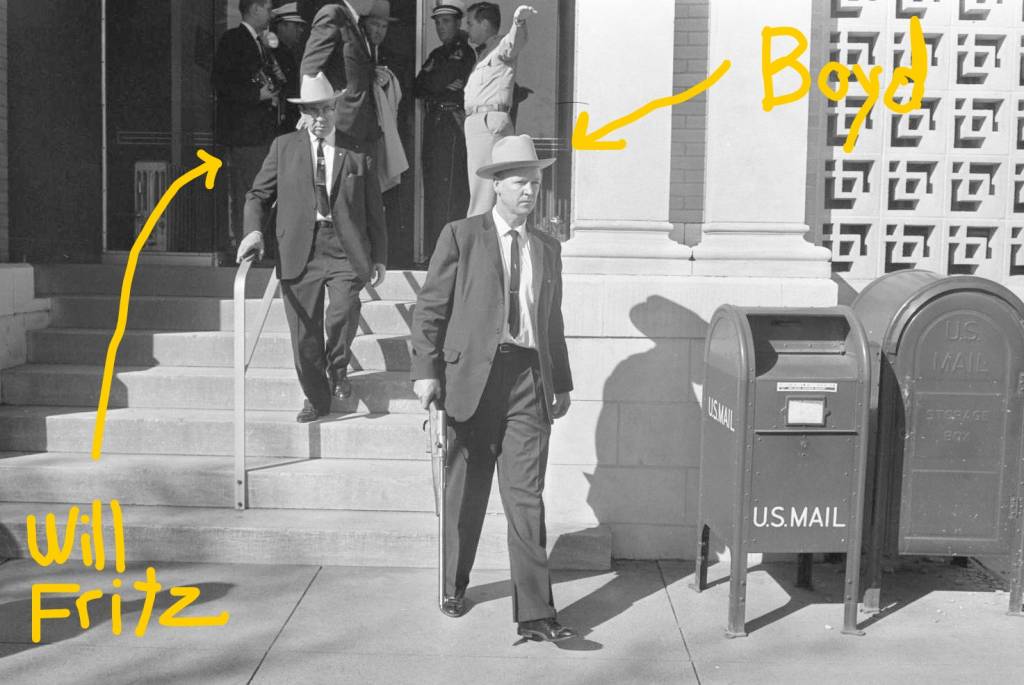

After high school graduation, he spent two years in the Navy. Boyd joined Dallas’ police force (badge number 840) in May 1952 and was there until 1978, at which time he began serving in Euless—a town considerably smaller and less hectic. Retired since 1988, he views conspiracy claims as nonsense. “There is no doubt in my mind that Lee Harvey Oswald killed our president and J.D. Tippit,” he told a reporter in 2013.

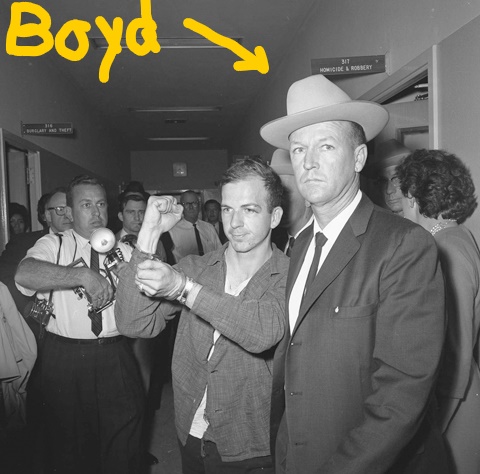

On November 22, 1963, Boyd’s duties commenced at the Trade Mart where Kennedy was to speak at a luncheon, then Parkland Hospital, Dealey Plaza, the School Book Depository (he was among the first to see Oswald’s Mannlicher-Carcano and three spent shells) and the frenetic scenes at DPD headquarters. Boyd, Fritz and other detectives interrogated Oswald but had to let Secret Service and FBI agents toss questions to the prisoner as well.

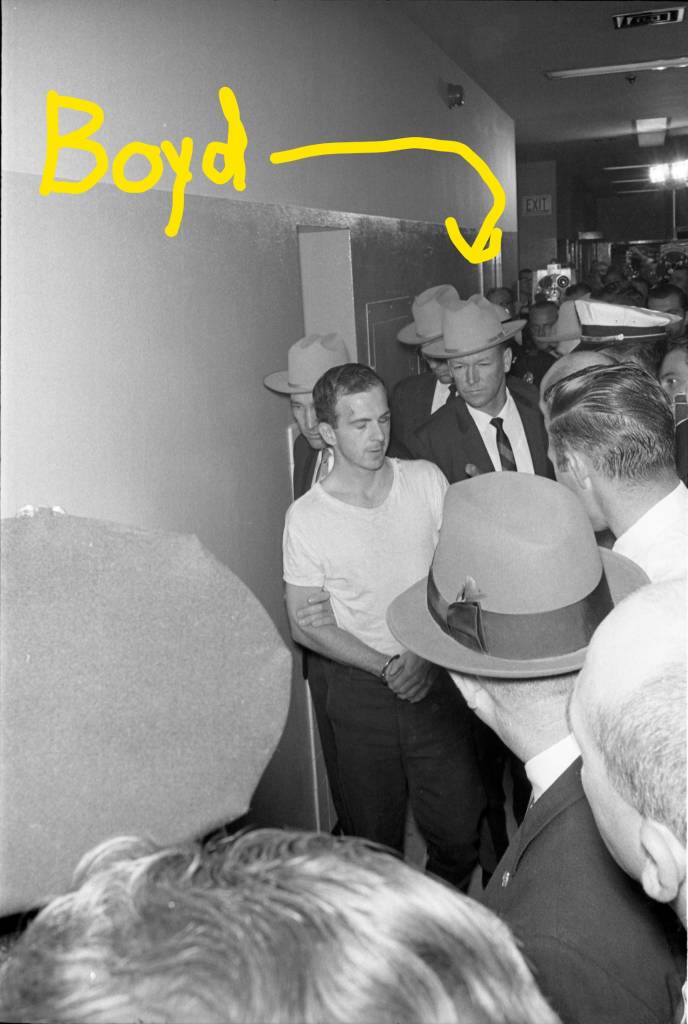

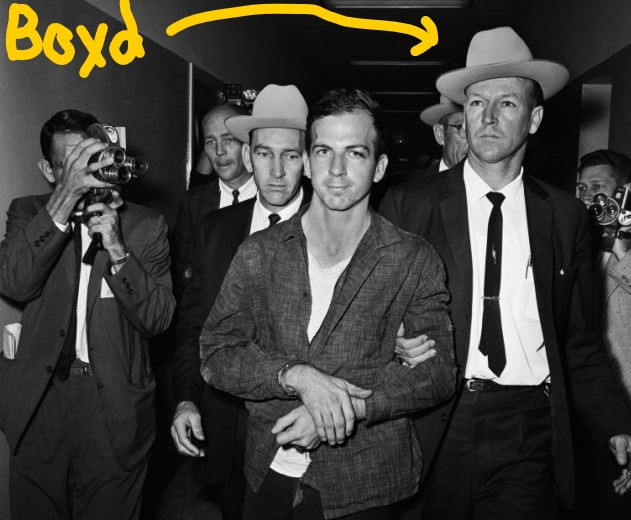

Photos of Boyd guarding Oswald show him with a hard face and cold eyes, as befitted a cop who had already conducted many homicide investigations. But a clip of him being interviewed at a JFK symposium years later gives a very different impression—a friendly, relaxed man who has grown accustomed to telling his story. This, I surmise, is the father Pam and her sisters knew and loved, the long-time husband of a woman named Yvonne.

He later reminisced about Oswald’s cool demeanor on November 22. After bringing his “curtain rods” from Mrs. Paine’s garage in Irving, he killed the president and injured Connally, killed Tippit, tussled with McDonald at the Texas Theatre, underwent several hours of questioning (some of his answers were blatantly false, such as denying that he had gone to Mexico City in September) by both police and reporters, was booked for murder and had been in three lineups for identification purposes. His captors had given him no chance to shower or eat, and yet he did not seem tired or frazzled; he was handcuffed almost constantly. Despite being dyslexic and having a very poor education—Oswald once lived in an orphanage, and his family moved 22 times before he joined the Marines in 1956—he was far from dumb. He repeatedly called for legal representation and complained that his rights were being violated.

Boyd, who had visited Oswald’s rented room at 1026 North Beckley on Saturday, might not appreciate me saying that he, Curry, Fritz and the others should have had a tape recorder running every moment with Oswald. Of course, they did not know they would only have him for 45 hours—roughly from 2 p.m. Friday to 11 a.m. Sunday—and no trial would ever be held thanks to Ruby’s rash act in the basement. (In fact, Ruby, who always carried his pistol, had a chance to shoot Oswald on the chaotic third floor on Friday and Saturday, and demurred.)

The perp-walk was conducted for the sake of the media—the media! Maintaining the accused man’s security was of infinitely greater importance. Such a bone-headed decision cannot be blamed on Boyd but his superiors. Security in the basement was lax, and that is why Ruby was able to slip in after a visit to a nearby Western Union in which he wired $25 to Karen Bennett Carlin (“Little Lynn”), one of his Carousel Club strippers. Four minutes separated that financial transaction and him pulling the trigger.

Boyd would have been handcuffed to Oswald as they walked toward the transfer vehicle on Sunday morning, but he had worked until 3 a.m. and went home for some rest. That made Jim Leavelle rather than Elmer Boyd the grimacing face in photos and videos seen all over the world. He should not be considered forgotten, however. “Not a week goes by that I don’t receive something, a phone call or photos, regarding those hours and days after the president was shot,” he said.

Add Comment