I have been to Hahoe Folk Village near Andong, the Minsok Folk Village in Yongin, the Jeonju Hanok Village and maybe a couple of others in my travels around Korea over the last 13 years. All of them have their charms. But when my friend Teresa Kim invited me to tour Oeam Folk Village near Asan recently, I could not say no. A one-hour bus trip south on the Gyeongbu Expressway was all it took.

Even before entering the front gate, Teresa and I had begun to learn more about it. A historical plaque summarized, in Korean and English, the history of the place. Oeam’s location, low on the southwest side of Seolhwa Mountain, was no accident. This way, the villagers got extra sunshine and were protected from cold winds blowing from the north in winter. But let us not forget pungsu-jiri-seol, the Korean version of Chinese feng shui. Putting a home or village in a certain spot based on astronomical, astrological, mathematical and cosmological factors was thought to be auspicious for life in this world and the next. Oeam seems to have been well placed.

People had lived there long before Yi Sa-jong moved in during the reign of King Myeongjong (1545−1567). This seems to have been a watershed event in the history of Oeam. He married one of Jin Han-pyeong’s daughters, and they prospered. The Yi clan produced numerous talented and high-achieving people, and Oeam soon had the look of a village of neo-Confucian nobles.

A tour guide was available, but only for groups of at least five. That policy was apparently flexible because a lady, Ms. Lee, joined us on a one-hour walk around and between the many homes. They include Pungdeokdaek, Chambongdaek, Sinchangdaek and Gyosudaek. They are named according to the house owner’s official name or hometown. Some of them had ponds and gardens, and almost all had waterways—although they were bone-dry during our visit. The village, with 6,000 meters of well-preserved stone walls, is a treasure-trove of Korean cultural heritage.

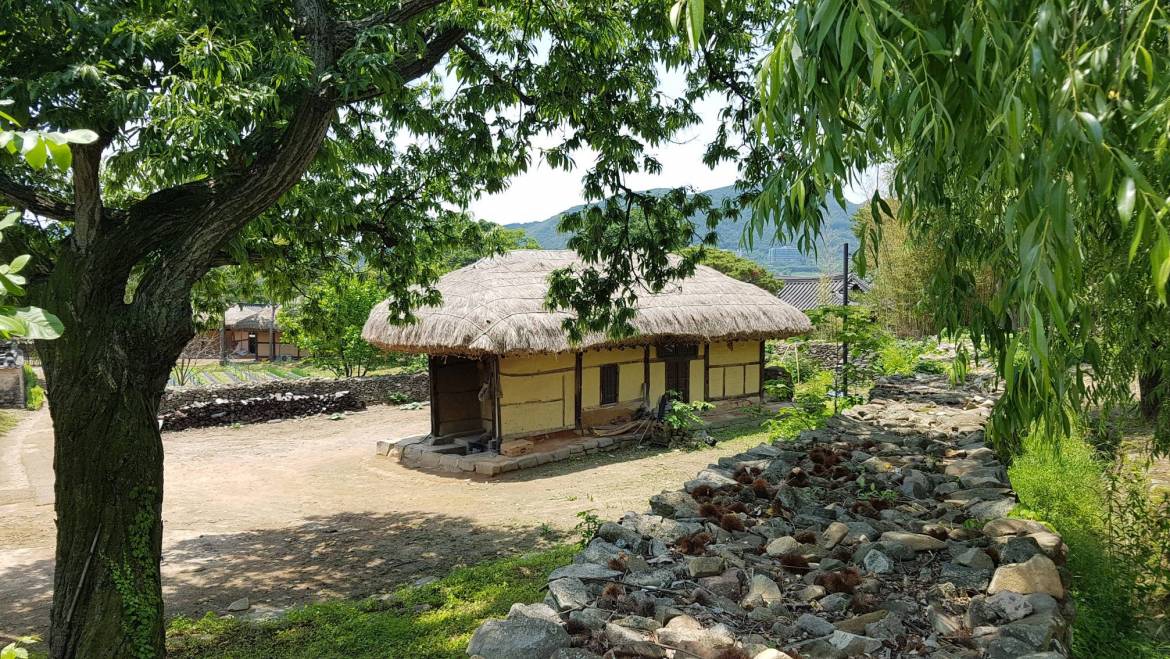

As we ambled from one spot to another, Ms. Lee educated us and answered questions. Teresa’s were in Korean, mine in English with her serving as a crucial translator. She told us that the bigger houses with tile roofs were for noble families and those with thatch roofs were for commoners and servants in the old days. All of the former seemed to be occupied, whereas the latter were just for show.

About 130 people now live in the village, Ms. Lee said. Most of them are fairly old, although one couple in their 20s recently moved in. There are no kids. This is a concern, she admitted.

She was not shy in calling Oeam the most authentic of Korea’s folk villages, telling us about the 600-year-old zelkova tree below which so many generations of people had gathered. I paused and looked it, pondering all the history it had witnessed. She told us about the tomb of scholar and civil minister Oean Lee Gan (1677−1727), the cultural festival held there every October, Korean traditional totem poles, the nearby pine forest and how the locals grow much of their own food. Ms. Lee said we were free to partake of “temple stay” at nearby Songamsa, but that was a no-go for us both. How about Asan Hot Springs or Onyang Hot Springs? Both are lovely establishments, but I had sampled them already.

Via Teresa, I asked a couple of questions that put her a bit off balance. The first pertained to the Korean War. Had there been fighting in the vicinity of Oeam during that bloody conflict? For all we knew, the village had been destroyed and rebuilt in the last seven decades. Teresa told me in a sub-rosa voice that this was a sensitive subject and that Ms. Lee seemed disinclined to talk about it.

When we came to a shady spot, I posed another question that I knew she might have trouble answering. It was about Saemaeul undong, the political initiative launched by President Park Chung-hee in 1970 which was intended to help modernize the rural South Korean economy. The movement sought to create autonomy in such villages as Oeam, based on communal ideals like hyangyak and doorae. The people labored to improve basic living conditions and later took on infrastructure projects.

I had recently read a couple of books on Korean history, both of which indicated that there had been a degree of coercion in many of these noble efforts. I asked Ms. Lee, was that true? Were some people forced to dig ditches, build fences and whatever? It was immediately apparent that she found that very question offensive. She insisted that all labor done in Oeam during Saemaeul undong had been completely voluntary; if people did not want to participate, they did not have to.

I felt bad about putting her on the spot and halfway wished I had not asked the question. The three of us soon began moseying down to the front gate. Before leaving, I took note of some elderly women selling locally grown produce. I paid 10,000 won for some succulent blackberries.

#koreantravels, #expatinkorea, #folkvillage, #culturalhistory, #asanhotsprings, #onyanaghotsprings, #seolhwamountain

Add Comment