Nearing the end of my freshman year at the University of Texas, I was not sure what to do in June, July and August. If I had possessed wisdom, maturity and direction—which I most certainly did not in those days—I might have stayed in Austin to take some classes or gotten an internship in a field related to my major. Perhaps I could have landed a temp job at the nearby Texas capitol. But a more interesting possibility arose in discussions with my dormitory friend Baxter Stanley. His father was a big shot with the Houston Barge Line, and that company had some open spots for young men willing to work. Baxter, who had been a deck hand the previous two summers and was aiming to become a pilot, gave me a fairly candid description of what the job entailed. There would be 12-hour shifts, physical labor of every kind and close proximity with people who were not exactly broad minded, to put it in a nice way. He warned me shortly after I signed up not to get into any political discussions.

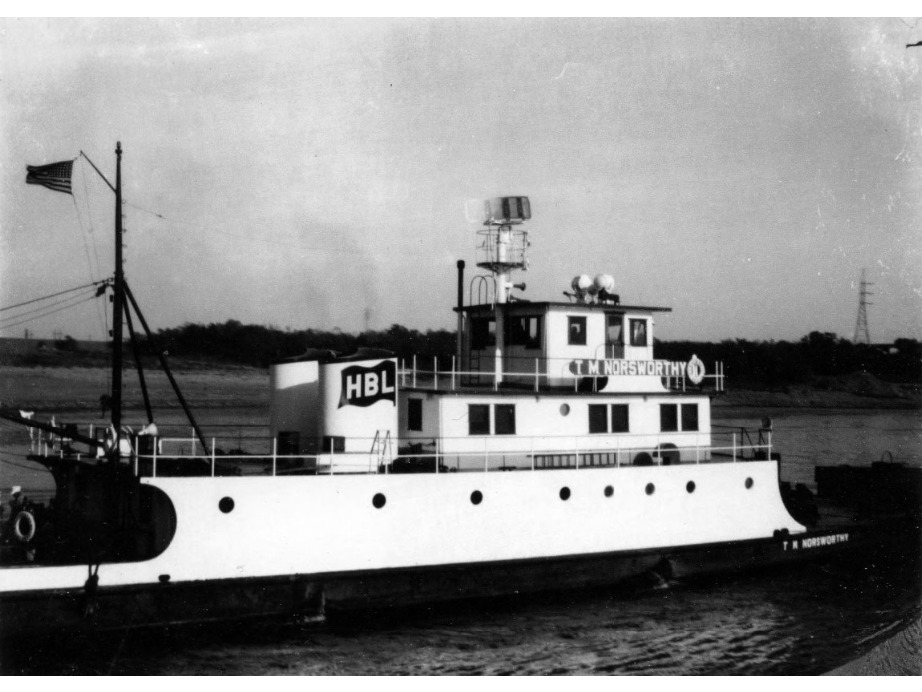

That summer I would be a deck hand on the T.M. Norsworthy, a tugboat plying the Mississippi, Ohio and Tennessee rivers. Such maritime vessels are given feminine pronouns, and so I will follow convention. She was built in 1952 and had four levels, the first of which was devoted to a ferociously loud, 3,000-horsepower engine. There were living quarters, a dining area and the pilot’s wheelhouse on top. The T.M. Norsworthy pushed eight large tanker barges carrying tons of refined asphalt. When the barges were full, they sat slightly above the water; when empty, they rose up 10 feet or more.

I met my co-workers, who included men named Andy, Howard, Frank, Nelson and Joe. The latter was the first mate, hailing from Cape Girardeau, Missouri. There was the cook, Opal Lee, a Tennessee native, and the only female member of the crew. She seemed grateful to me because I asked her questions and spoke to her respectfully, which some of the others did not. As best I recall, the rest of the men were from Texas and Louisiana. They were cordial enough but still somewhat skeptical of the college boy who was just there for the summer. For many of them, it was full-time work and in some cases their careers. It is quite possible that one or two of them had seen the inside of a jail. How could they not resent me? Nevertheless, I was determined to show that, although I was on the boat temporarily, I could contribute. That meant being willing to take orders, do dirty work and not complain.

When the barges were loaded with asphalt and we were going upriver, it seemed that we moved at a snail’s pace. In fact, I was informed that we were going four miles per hour, which would come to almost 100 miles per day. The first trip I made in the summer of 1972 was from Norco, Louisiana to Wood River, Illinois—straight up the Mississippi River. In fact, that huge river, 2,320 miles long and more than a mile across in some places, is anything but straight. There are twists, turns and oxbows to be navigated, not to mention islands here and there. I recall no accidents or even incidents with the many other ships navigating those waters, but the pilots bore a heavy responsibility. Small errors could lead to major disasters.

I was on the T.M. Norsworthy just one summer, but I really saw a lot of America. I recall going through the “locks” on the various rivers as we were raised or lowered 40 or so feet at a time. I recall riding along the Ohio River, admiring one beautiful green mountain after another and wishing I could own just one of them. I recall the time we made port in Knoxville and were able to see Neyland Stadium, home of the University of Tennessee Volunteers. One night, we had stopped at Marietta, Ohio. I went ashore with the idea of exploring the oldest city in that state, but I was soon disoriented and completely lost. Some kind people directed me back to where I needed to be.

A company called Waterway Marine, based in Memphis, brought mail from my then-girlfriend Pam Grover and others. They would send a boat out into the river with mail and various supplies. When we went back to Norco, my comrades and I were loading bundles of rags on one of the empty and thus high-sitting barges. This required going up and down a ladder. I had a misstep and tumbled into the dirty water. The others laughed with glee although my head nearly landed on a piece of jagged steel. When I later wrote to Pam about this, her response was a reminder of what she had said when we departed at UT a few weeks earlier: “Don’t fall off the boat!”

I got wet one other time that summer. When the T.M. Norsworthy was at a port in the Mississippi, a fellow deck hand named Howard challenged me to jump with him into the river. We ran side by side atop one of the barges, but he halted whereas I continued on. I looked up to find him and many others cackling as I found out first-hand how strong the river’s current was. It took quite a while before I was able to make my way to shore and then back to the boat.

Despite Baxter’s warning, I sometimes got into discussions that traversed dangerous areas. All of my colleagues were of European-American descent. In fact, I hardly recall seeing another black person on any of the rivers that summer. It should come as no surprise that they were, to varying degrees, racist. One night, I was talking with Andy in our bunk beds and made a comment about fairness and justice for black people. This otherwise calm and friendly man then flew into a rage with all sorts of bitter denunciations. I immediately gave up on expressing a counter viewpoint and sought to soothe his feathers. I could only imagine what in his past caused him to have such a sadly negative attitude.

My time on the T.M. Norsworthy ended a bit prematurely and with haste. I had grown bored with the routine and most of the people with whom I worked. In early August 1972, I gathered my belongings and told the pilot and first mate that I was getting off at the next stop, which turned out to be Evansville, Indiana. The money I had made was sitting in a bank account, and most of it would be used to buy a Honda motorcycle. First, however, I had to get home. I located the bus station in Evansville and purchased a ticket to Dallas. I had to wait several hours before departure, so I went outside. I sat there in the heat, ruminating about the summer’s experiences when I noticed a man in a sports car driving by over and over. He eventually stopped and introduced himself. Want to come for a ride? I sure did. It was exhilarating to be back on dry land, eating a hamburger and drinking a Coke in a speedy convertible, and having fun before I went back to Texas. He was a nice guy. But the time came, almost inevitably, when his sexual inclination was manifested. I rolled my eyes and said, “No thanks. Take me back to the bus station.”

3 Comments

That job was not for you, but if you still tried it was a life lesson like many others probably.

Let’s prepare for the celebration of the birth of the Lord Jesus, soon Christmas is knocking at the door.

Happy celebrations !

So true, Elly…it was not for me! Surely I could have found a better summer job after my freshman year in college. This is one of many foolish mistakes I have made and yet somehow survived.

Summer jobs were great things for young guys like us. They pay was far better than what young folks make these days and the “lifers” gave us advice (usually unsolicited) that can’t be read off a page of a book. Dangers abounded and successfully escaping them made us appreciate what opportunities we had when school began. To this day, I’m grateful for the scalding hot water in the hospital dishroom, the heat/grime of the power plant, and the earsplitting noises of the steel mill. They were my way out of the old neighborhood which was on the wrong side of the river as well as the wrong side of the railroad tracks. Thanks for the memories, RAP.

Add Comment