This is a tale about history, culture and petty vandalism in Austin, Texas. Come with me back to 1976, the year of the American bicentennial. A recent college graduate, I was driving a delivery car—a red Ford mini-truck, to be specific—around the city for Burks Reproduction, a company that made copies and bluelines for architects and builders. Although I had been in Austin most of the past five years, I came to know it much better as a result of that job. There were days when I drove more than 100 miles, all inside the city limits. We were based on the perpetually busy North Lamar Boulevard, just south of 45th Street. Fewer than 20 blocks up the road sat the remains of Kenneth Threadgill’s gas station, which had been much more than a gas station.

In 1933, during the Great Depression, he opened it on the outskirts of town on what was then called Dallas Highway. Almost from the beginning, Threadgill welcomed singers and guitar players entertaining themselves and patrons. He himself was an accomplished singer and yodeler. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, his establishment began drawing bohemian students from the University of Texas who loved folk music. One of them was Janis Joplin, a native of Port Arthur. She was raw but talented, and Threadgill encouraged her. She never finished her studies, heading instead to San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury  district in the height of the hippie era. Joplin became the lead singer of Big Brother and the Holding Company, a rock & roll band of considerable renown. They played to big crowds at places like the Fillmore East, the Avalon Ballroom, the Hollywood Bowl, Golden Gate Park, Madison Square Garden, Shea Stadium, the Monterey Pop Festival and Woodstock. They toured the U.S., Canada, Europe and South America. Wherever they went, most of the attention was focused on the frenetic girl with the microphone. Joplin later sang for a couple of other bands and did solo work. She sold a lot of records, made some money and wasted nearly all of it. A person with many insecurities, Janis Joplin died of a heroin overdose, combined with the effects of alcohol, on October 4, 1970 at the age of 27.

district in the height of the hippie era. Joplin became the lead singer of Big Brother and the Holding Company, a rock & roll band of considerable renown. They played to big crowds at places like the Fillmore East, the Avalon Ballroom, the Hollywood Bowl, Golden Gate Park, Madison Square Garden, Shea Stadium, the Monterey Pop Festival and Woodstock. They toured the U.S., Canada, Europe and South America. Wherever they went, most of the attention was focused on the frenetic girl with the microphone. Joplin later sang for a couple of other bands and did solo work. She sold a lot of records, made some money and wasted nearly all of it. A person with many insecurities, Janis Joplin died of a heroin overdose, combined with the effects of alcohol, on October 4, 1970 at the age of 27.

Threadgill’s old gas station/music joint, which closed four years later, seemed to have no future. It had suffered damage from a fire, and weeds and other vegetation abounded. At this point in the story, I must turn the focus on myself. In 1976, I was living on West 29th Street on the second floor of a  subdivided old house. One entire wall of my room was devoted to handbills for a variety of music venues—most especially Armadillo World Headquarters, a place of legendary artistic and cultural creativity. I was aware of the stories about Joplin singing at Threadgill’s half a generation earlier and was quite saddened to see it in such a state.

subdivided old house. One entire wall of my room was devoted to handbills for a variety of music venues—most especially Armadillo World Headquarters, a place of legendary artistic and cultural creativity. I was aware of the stories about Joplin singing at Threadgill’s half a generation earlier and was quite saddened to see it in such a state.

I have written elsewhere about my disdain for graffiti. Nonetheless, I started thinking about a one-time foray into that rather pathetic activity. It would not, however, be the “tagging” done by gang-bangers or those with no regard for public property. I had justification for what I was about to do. On a hot, muggy summer night, I drove my car to a convenience store on North Lamar, directly across from the 43-year-old filling station which seemed unlikely to escape the wrecking ball much longer. I went in and purchased a can of blue spray paint. I nervously crossed the street, looked around and wrote the words “Janis sang here” on the wall facing the street before high-tailing it back home.

The next day, I informed Dan, one of my co-workers at Burks. He was a moderately successful musician himself. Dan was supportive but asked why I had done it. “To commemorate her spirit!” I said rather loudly. I smiled every time I drove by there, admiring my handiwork.

I left Austin in late 1976 for Dallas, then Kentucky, then North Carolina, then Denton. By the time I got back to Texas’ capital in the early 1980s, things were different. To my great astonishment, Threadgill’s had survived. The aforementioned Armadillo World Headquarters on Barton Springs Road had closed and been razed, but its founder, Eddie Wilson, saw potential in the old gas station. He turned it into a very popular restaurant named, appropriately enough, Threadgill’s. (I have eaten there countless times—I recommend the three-vegetable plate with cornbread and iced tea.) Of course, my bit of graffiti had faded and been covered up. That would seem to be the end of it, right? Not quite.

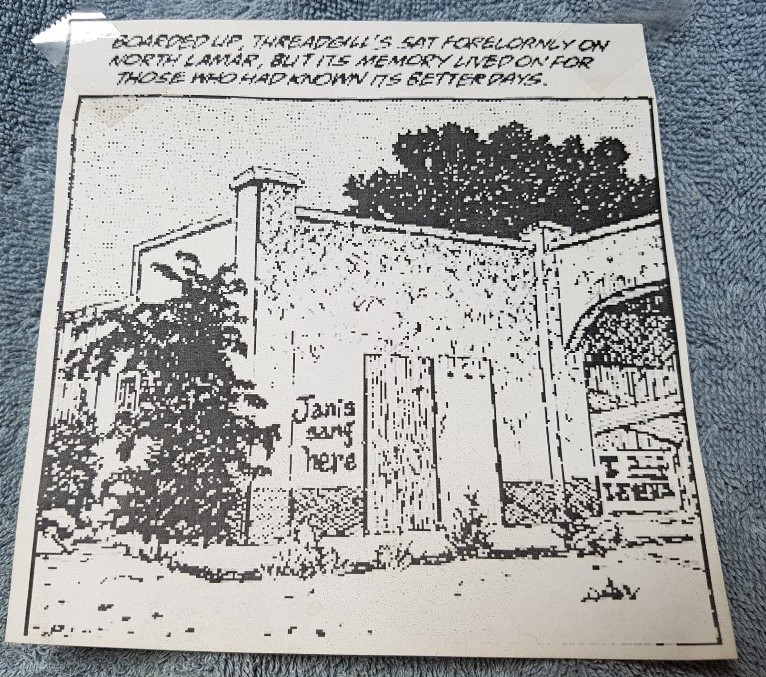

Walk in the front door of Wilson’s southern food emporium and you will see a framed photograph of the building, circa 1978, with “Janis sang here” on the front. Joplin’s younger sister Laura wrote a book, and  the photo section included you know what: “Janis sang here.” David Allan Coe used “Janis sang here” in the lyrics of one of his songs. And finally, an artist named Jack Jackson—whose wife, coincidentally, I once worked with—compiled a comic book history of Threadgill’s. Naturally, it included a frame of “Janis sang here.”

the photo section included you know what: “Janis sang here.” David Allan Coe used “Janis sang here” in the lyrics of one of his songs. And finally, an artist named Jack Jackson—whose wife, coincidentally, I once worked with—compiled a comic book history of Threadgill’s. Naturally, it included a frame of “Janis sang here.”

I do not want to give myself too much credit, but my one act of vandalism-for-a-good-cause seems to have had meaning for others. Maybe it helped remind Wilson of the considerable history of that building and spurred him to save it. As for Joplin herself, during four years of meteoric fame she earned a reputation as one of the best female rock & roll singers of all time. Port Arthur, the city where she was once an outcast, has honored her in numerous ways. Besides the biography written by her sister, there have been at least five others, not to mention a movie and a Broadway play.

Add Comment