I am writing this just a couple of hours after Eli Manning led the New York Giants to their second Super Bowl victory (21-17 over the New England Patriots) in four years. He was named the game’s MVP. I like Manning and his low-key demeanor, and he has really proven himself as one of the top quarterbacks in the National Football League. His more famous brother, Peyton, has won one Super Bowl with the Indianapolis Colts.

I nearly met Manning eight years ago. My use of that adverb may be explained only by returning to yesteryear when his father was in college. Archie Manning, like both of his sons, played quarterback at an institution of higher learning in the Southeastern Conference. He and Eli both went to Ole Miss, whereas Peyton chose to play for the Tennessee Volunteers. Neither of his boys is especially mobile; instead, they are schooled in the fine points of drop-back passing. Archie, though, could run like the wind and escape tacklers with ease, and he was a fine passer as well. It must be admitted that when he played (1968–1970), the SEC had barely begun the integration process. In fact, Manning had no black teammates when he played for the Rebels. He was an all-American and finished third in Heisman Trophy voting as a senior.

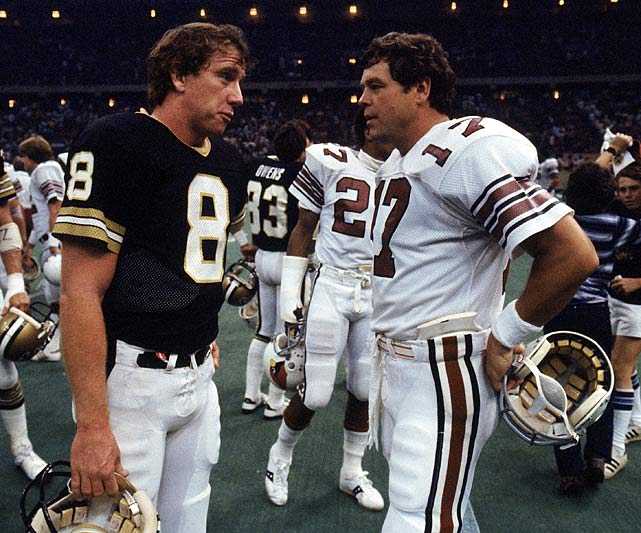

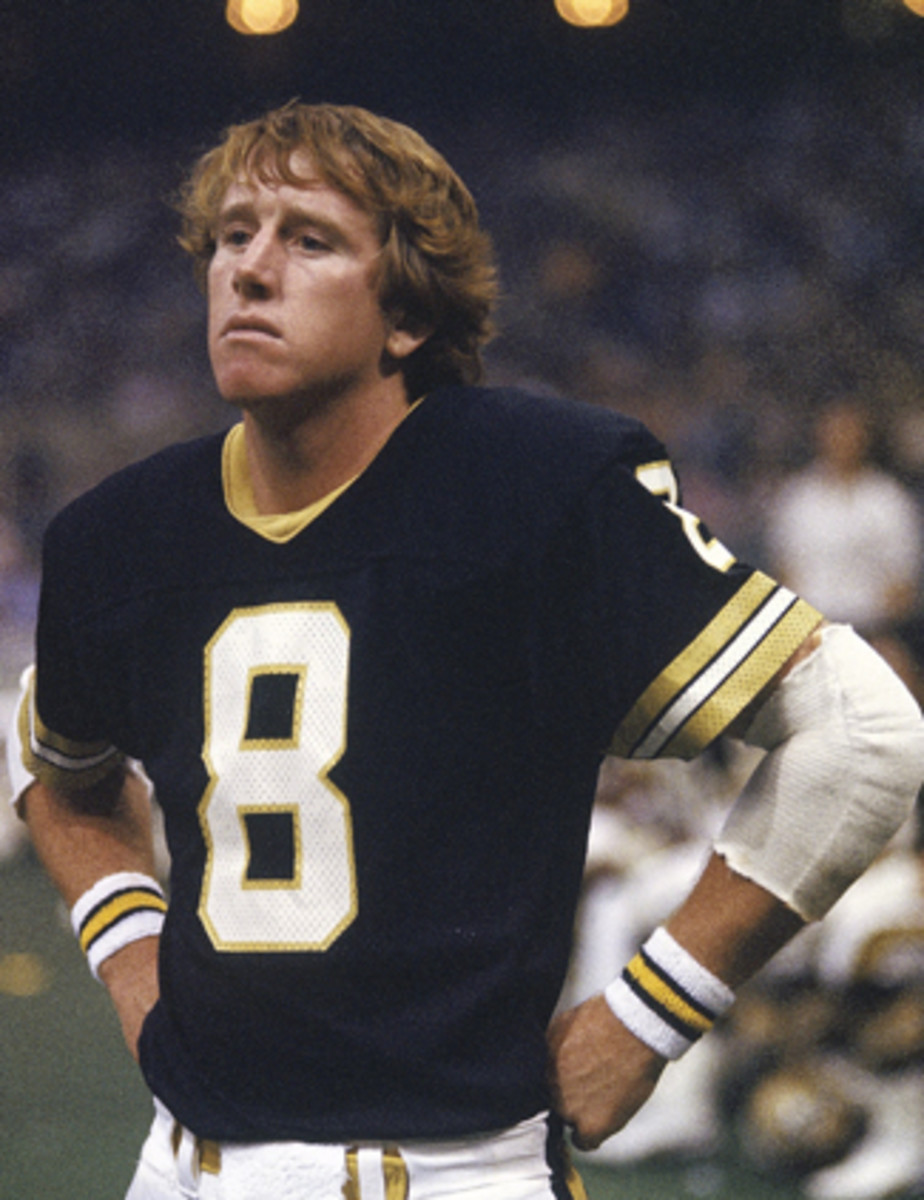

The New Orleans Saints made him the second pick in the 1971 NFL draft. Through no fault of his own, the Saints were uniformly awful during his 10 years with the team. They never reached the playoffs. He finished his 13-year career in a desultory manner with the Houston Oilers and Minnesota Vikings. Manning’s record was 35-101-3, which is the worst winning percentage among quarterbacks with at least 100 starts. That should not obscure the fact that Archie Manning was a superb quarterback, both in college and in the pros.

Peyton and Eli also had fine careers in Knoxville and Oxford, respectively. The former was the No. 1 pick by the Colts in the 1998 draft, and the latter was chosen No. 1 overall by the Giants six years after that. Dad and both sons got the imprimatur of being drafted at the very top. As we have seen, however, Archie came nowhere near a Super Bowl while both Peyton and Eli have rings. (As of today, Eli has two.)

Shortly after the Giants drafted Eli in ’04, I was at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel in New York. I snuck into one of the preliminary events for the College Football Hall of Fame induction ceremony. I had come a long way to honor Jerry LeVias, SMU’s great receiver from 1966 to 1968 and the first black player in Southwest Conference history. He would be among the inductees the next night. Archie had been in the Hall since 1989, and when I saw him in this fairly crowded room I simply had to introduce myself. Of course, when doing such a thing there is never a guarantee of a warm reception. “Super” Manning, as they used to call him at Mississippi, deigned to shake my hand, but that was about it. He literally did not bother to look at me since, in his mind, he was a somebody and I was a nobody. I recognized Eli nearby, but after that ice-cold meeting with his father I had little desire to try again. One snub in an evening was enough.

I recall four other such instances, all of which took place in Austin. The first involved Eric Metcalf, a scintillating running back/kick returner at UT from 1985 to 1988. (In a 14-year NFL career [primarily with the Cleveland Browns and Atlanta Falcons], he scored 55 touchdowns and had more than 17,000 yards in total offense.) I met him in the stands at Memorial Stadium and wanted to say how much his play reminded me of his studly father, Terry Metcalf, while he was with the St. Louis Cardinals. Much like Manning had done, he gave me a limp handshake and ignored my father–son comparison. How little he cared was on full display.

Not too long after that, I went with a friend named Richard Taglienti to Earl Campbell’s barbecue restaurant on Sixth Street. Richard and I wanted the BBQ, but we also hoped to meet Campbell, winner of the 1977 Heisman Trophy in his senior year at Texas. Playing for the Houston Oilers, he led the NFL in rushing his first three years. Most people know Earl Campbell and would agree he is one of the best to ever tote a football. At any rate, Richard and I found him in his restaurant. We made sure that we were not intruding, but he seemed rather displeased about having to acknowledge our presence. In his case, I was somewhat more forgiving. Campbell, once the most indestructible of men, was in bad shape. He had a severe case of arthritis, his knees were shot, his back ached constantly, and he had a condition known as “drop foot”; due to nerve damage from his playing days, he was unable to raise the front of his feet when he tried to take a step. The gray-haired Campbell now walks with a cane—at least when he is not in a wheelchair.

Third was Spencer Heywood, who I met in an auditorium after a presentation, the nature of which I simply do not remember. He had no bigger fan than me. I had seen him terrorize the American Basketball Association (with the Denver Rockets) before jumping to the NBA’s Seattle SuperSonics. Oh, what a player—30 points and 19 rebounds per game as a 20-year-old rookie, are you kidding me? Having witnessed his act several times at Moody Coliseum against my Dallas Chaparrals, I truly wanted to meet him. Since Heywood stood 6′ 9″, I had to look almost straight up. He might have been warm, cordial and unpretentious because I have met enough big-time athletes who are that way. But no.

Finally, we come to Alberto Salazar—winner of the New York Marathon thrice and Boston once in the early 1980s. He had been invited to Austin by Run-Tex, a well-known running store. Salazar spoke to a group of us and then offered to go out for a short run on the nearby hike-and-bike trail alongside Town Lake. I joined in and went up to the front of the pack; it was a slow pace for this iconic runner, even twenty years after his heyday. I made what I considered fairly innocuous comments and asked a question or two. By now, you can guess his response. Alberto, like Archie, Eric, Earl and Spencer, perceived me as a nuisance.

Many jocks, whether active or retired, have had pampered lives. Since junior high school, someone has been telling them how great they are and catering to their every need or desire. Being the focus of attention is natural for them, and they grow accustomed to the red-carpet treatment. But the reality is that most of these guys are not very interesting people. Having had to work in such a single-minded manner to get to the top of their sport, they know little else. If the five gentlemen I have written about here dismissed me without a second thought, that was their prerogative. I really did not take it too personally.

2 Comments

I had a similar experience with all-time MLB prima donna Cal RIpken. He refused to sign a ball I offered and returned it to me in a I’m-somebody-you’re-nobody manner. F him.

Cal??? He has such a great public reputation….very interesting! he can join Archie, Spencer, et al. I will give another example, of the positive variety. I refer to Raymond Berry, the former Baltimore Colts receiver who made such a good combo with Johnny Unitas. He had coached the New England Patriots to the Super Bowl after the 1985 season. We met, and he was the opposite to these gentlemen. Berry gave me full respect, listened closely to what I said, gave considered answers…no “attitude”

Add Comment