When I decided to move to Korea more than seven years ago, I harbored a wish and a dream: maybe I could visit the fabled city of Shanghai, located just across the Yellow Sea. But until recently, I was not prepared to go there. I needed a better grasp of the history and culture of east Asia. Excessive as it may seem, in late 2014 and early 2015 I devoured 11 books about Shanghai, China, and the Communist revolution of 1949 and its aftermath. I was ready.

Awaiting my flight at the Seoul airport, I saw a string quartet playing for travelers and a group of Korean Air Lines stewardesses; I wondered whether any of them had ever been browbeaten by Heather Cho. I arrived at Pudong International Airport on Thursday night. Given that it was the Lunar New Year (year of the sheep, they say) and that Shanghai is home to more than 25 million people, I expected chaos, noise and above all crowds. In fact, it was the opposite as I sailed through baggage claim, security and customs. I rode the subway in a northwesterly direction to the city proper. A taxi brought me to my home for the next five days—the Astor House Hotel, on the west side of the Huangpu River, just over the historic Garden Bridge and on the north bank of Suzhou Creek.

A few words about Astor House, which has been at that spot for nearly 160 years. Center for the glittering social life of Shanghai’s international community until the 1920s, it has been expanded and renovated numerous times. The exterior is made of stone, but the framework is wooden and thus the floors “give” just a little and squeak when you walk down the narrow halls. Many famous men and women had stayed there, including U.S. Grant, Jim Thorpe, Charlie Chaplin, George Bernard Shaw, Albert Einstein and Chou En-Lai. Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek allegedly spent his final night on the mainland at Astor House before fleeing to Taiwan. Astor House’s fortunes had risen and fallen more than once, and I am surprised if not amazed that it has managed to endure the vicissitudes of time. I paid a piddling $61 per night.

I ran all five mornings I spent in Shanghai, usually on the Bund—the landmark waterfront once known as the Wall Street of Asia. It curves for about a mile along the Huangpu, from Yan’an Road to the Garden Bridge. Facing the river are large buildings designed and constructed for one purpose: finance, specifically Western-style capitalism. They include the Royal Dutch Shell Building, the Shanghai Club, the Union Building, the Mercantile Bank of London, India and China, the Customs House, the North China Daily News Building, the Palace Hotel, Sassoon House, the Bank of China Building and the Yangtze Insurance Building. All were confiscated after formation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), renamed and sometimes put to entirely different uses. My favorite story pertains to the Bank of China. There, one night in 1949 when it had become clear that the Republic of China (ROC) was about to lose the civil war, the wily Chiang ordered dozens of his soldiers to put on “coolie” outfits and transfer 114 tons of gold to ships waiting on the shore of the Huangpu before departing for Taiwan. When representatives of the PRC arrived soon thereafter, the vaults were almost entirely empty.

The British Concession, the French Concession and the American Concession were large swaths of central Shanghai that had been “conceded” in the mid-19th century wherein these foreigners and others (Baghdadi Jews, White Russians, Germans, et al.) did business and dominated socially. I exaggerate only slightly by saying that a Jim Crow or even apartheid situation existed for a long time. A sign in the Public Garden at the north end of the Bund made clear that Chinese were forbidden to enter. People of European descent were at the top of the hierarchy. These slights built up over the years, and when the revolution came they provided fuel for the natives’ anger.

Beside the Bund is a statue of Chen Yi, mayor of Shanghai from 1949 to 1958. I make reference to this only because it is the site of a recent tragedy. On New Year’s Eve, a crowd of 300,000 gathered. For reasons that remain unclear, a stampede occurred in which 36 people were killed and 49 injured. Chinese media made no reports about the incident until January 2, justifying this delay by saying that “authorization” was necessary.

I had breakfast every morning in Astor House’s Peacock Hall, a place where so much history had transpired—the famous “tea dances,” the playing of the first sound film in China, the People’s Liberation Army taking over in ’49, the inauguration of the Shanghai Stock Exchange in 1990 and more. This is where I met two lovely young women, Cathy and Alicia, from Anhui Province. Both were doing internships as part of their tourism degrees for a university back home. I also must mention Bob, one of the hotel’s doormen. He was always eager to talk, call me a taxi or help in other ways. Bob had some backward ideas, however. He could not understand why I, an American, would want to live in Korea. He regarded it as a small, weak and insignificant country. Bob also opined that Korean women were unattractive. My efforts to convince him that Korea is an economic and cultural powerhouse, and that many of its women are quite beautiful were to no avail.

Friday, February 20 was a windy day. I walked south to Gucheng Park and speculated about “struggle sessions” that may have been conducted there during the so-called Cultural Revolution (1966−1976). During that time, Mao Zedong encouraged the Red Guards to humiliate and abuse “counter-revolutionaries.” Such frenzied gatherings took place at factories, universities, sports stadiums and parks like Gucheng. Dunce caps were often placed on the heads of victims, and placards were hung around their necks stating their supposed crimes. These people were beaten and sometimes killed or driven to suicide, all under the pretext of self-criticism and rehabilitation. Truly a shameful aspect of modern Chinese history.

On a somewhat related topic, I should recall my visit to the Business Center on the second floor of Astor House. While I said I wanted to use a computer to check my e-mail, that was merely a ruse. I was allowed to do so, but I had to give my name and the number of my passport. Nevertheless, I was curious and so I divulged the information. I had heard about conflicts between Google and the PRC, and sure enough I was unable to use that most popular of search engines. I went to Yahoo instead, typed in “Tiananmen Square protests” and waited to see what would happen. As expected, I got an error message. A quarter-century after those fairly benign requests for political reform were crushed by the military, people there cannot read the full story and better not talk about it out loud. The country is a one-party system, and Beijing (known euphemistically as “the center”) has imposed a sort of amnesia on its 1.3 billion people. The bargain seems to be that they settle for economic growth—as if all are benefiting equally!—and the Communist Party maintains its firm hold on power. One might also be wise to abstain from searches about government corruption, environmental pollution, land issues or the horrific famine caused almost entirely by Mao’s policies in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

At 3 p.m., I stood outside the hotel and greeted Tommy King, a former high school classmate. I had actually chosen this date to come to Shanghai because of Tommy, who was there with his Chinese wife, Xu Ling Ning, for the New Year’s celebrations. It had been 44 years since we last saw each other, but I could recognize his face and muscular build—he had been quite a football star at Bryan Adams High School in the 1968, 1969 and 1970 seasons. We took a rather long taxi ride west to a sports bar he favored. There were TVs all around, with soccer, rugby, college basketball (Syracuse vs. Louisville) and baseball (replays of the 2014 World Series won by the San Francisco Giants). Tommy and I drank beer and ate nachos, and talked about the olden days. He has had a nice career with a series of companies that do major civil engineering projects. After an hour or so, we went to a different restaurant to meet his wife and stepdaughter, Xia Wen. I had hosted her in Seoul a month earlier; she looked good, even with her newly dyed green hair. The four of us had a sumptuous meal and then walked through Yuyuan Market, a must-visit place for tourists. I relied on Ling to help me bargain with shopkeepers for Shanghai T-shirts and other such items to take home. At least twice, we were walking out the door when the woman behind the counter shouted at us to come back. Our terms had been reluctantly accepted.

On Saturday morning, I ran along Suzhou Creek, a tributary of the Huangpu River. My purpose—unsuccessful, as it turned out—was to find the Sihuang Warehouse. Briefly stated, it was the site of a heroic defense by about 400 Chinese soldiers against a much larger and better equipped Japanese contingent from October 26 to November 1, 1937, which effectively ended the Battle of Shanghai. Germany’s invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939 is often called the beginning of World War II, but to Asians it was the Battle of Shanghai, a bloody fight that lasted three months and took the lives of nearly 350,000 people.

Following the instructions of Xia Wen the day before, I rode Line 3 of the subway north to Suichan Road Station, stepped out and practically had to fight for a taxi. After 10 minutes, I got one and gave the driver a note she had written which said, “I want to go to Binjiang Forest Park.” He brought me to a nice place with wild animals, pretty flowers, creeks, a waterfall, an amusement park and much more. I cared about none of that. I was determined to see the Yangtze, the longest river in Asia (3,915 miles) and the third longest in the world. Everybody, it seems, knows of this huge and historic body of water. I entered the park and walked for 10 minutes before coming upon the mighty Yangtze. It was so big, it looked like an ocean—albeit one with water flowing from west to east. Maybe on a clearer day, I would have been able to see the other side. I have now seen the Mississippi, the Nile and the Yangtze. Maybe someday I can go to Brazil and behold the Amazon.

While there, I met a handsome couple who spoke excellent English and went by the names of Luna and Icarus (he claimed to be a big fan of Greek culture). She kindly wrote a note stating that I wanted a taxi to take me back to Suichan Road Station. The ladies at the entrance of Binjiang Forest Park were unable to help me, however. They insisted that no taxi could be convinced to come there. Had I not taken a taxi to the park 90 minutes earlier? After fruitlessly begging and pleading, I walked out the door. I went to the parking lot with the idea of flagging down a departing car and hoping for the best. Lo and behold, the first one was enormously helpful. A woman named Leslie (again, fluent in English) read my note and escorted me to a nearby bus stop. The bus came barely 30 seconds later—I swear it’s the truth—and I thanked her profusely. I went back to town, but not to the hotel.

Near the top of my agenda was People’s Park (northern half) and People’s Square (southern half). For the sake of simplicity, I will use the latter designation. The new names were instituted, of course, after the Communists swept into power. “Liberation,” it is called. Just as all European-based street names were changed (Avenue Joffre –> Huaihai Road, Lincoln Avenue –> Tianshan Road, Avenue Foch –> Yanan Road, Bubbling Well Road –> Nanjing West Road, etc.), so was that of the Shanghai Race Course. There, starting in 1862 horse races were held, along with gambling, raffles and other games of chance. Mao took a dim view of such matters, considering them vestiges of colonialism. No more horse races, needless to say. And yet even today, the curve of streets around People’s Square shows where the ponies used to run. I was there twice during my stay in Shanghai, and it seemed like a happy, vibrant urban spot; Shanghai Museum and Shanghai Grand Theater are imposing edifices.

But the place has a dark history. In the 1950s, it was the site of numerous public trials and mass executions. A lot of blood was shed at People’s Square. (Some of the biggest and most severe “struggle sessions” from the so-called Cultural Revolution took place there as well.) I walked inside of it and around the perimeter, cogitating in a sour mood. Were all those deaths—or any of them—really necessary? I saw a couple of statues representing intrepid Chinese revolutionaries, but nothing about the hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people who were killed there. I know it is essentially the same point I made earlier about the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989, but this is a country in dire need of historical reckoning. On October 1 of every year, Mao’s statement that “the Chinese people have stood up” is repeated, in response to which I ask: How many of them were brought to their knees during his brutal era?

I have a couple more vignettes from People’s Square. Signs were posted with very specific rules and regulations. These included the “Seven Don’ts.” Two of them were “Do not relieve the bowels” and “Mentally ill persons may not visit the park alone.” There was also an area completely given over to parents who had set out notices in which suitable matches were sought for their adult children. I give you the English text of one: “London, UK. Female, born in Oct. 1974. 1.66 m in height, unmarried. Ph.D. at the London School of Economics & Political Science, now works in a famous university in London, has a green card. Looking for a boyfriend who, both a Chinese or a foreigner, is best in London or UK, Europe, North America and HK. [phone number and e-mail address].”

Everywhere on the Bund, on Nanjing Road and at important economic or political buildings, I saw serious-looking young men wearing heavy, olive-colored winter uniforms. Whether they were policemen, soldiers or some combination, I do not pretend to know. I noticed that people sometimes asked them for directions and they freely responded. But I do not doubt that they were there to show that the state is in control. Along much the same line, atop every building on the Bund I saw the PRC flag (red, with five golden stars in the top left corner) flying. It seemed to be a none-too-subtle reminder about who is in charge.

That night, I had an impossibly delicious dinner of fried rice, shrimp and chicken at a restaurant across the street from Astor House. The waitress who took my order and brought the food was friendly and efficient. I have no idea whether tipping is OK or not OK in China, but I put a 20 yuan bill on the table when I left. I went walking on the Bund, taking in the sights of the river, the historic buildings and the skyscrapers of Pudong. For the first time, the crowds of Shanghai seemed a bit suffocating.

Sunday was a memorable day. I rode the subway a few miles southwest to Xintiandi, a district that has been renovated and gentrified—maybe a bit too much for some critics. I had not come to study architecture, though. I located the two-story building where, in July 1921, Mao Zedong and 12 others had founded the Chinese Communist Party. As might be expected, there were depictions of Marx, Lenin and Mao, along with bold statements about how imperialism, feudalism and the bourgeoisie had been overthrown. Let’s hear it for the dictatorship of the proletariat!

A few blocks away was a building whose significance I found much more appealing: the office of the Korean Provisional Government (KPG). With the Japanese dominating their homeland, a number of Koreans gathered at this spot on April 13, 1919 to proclaim a government-in-exile. With such luminaries as Syngman Rhee, Kim Gu and Ahn Chang-ho, the KPG sought to undermine Japanese rule, formed guerilla bands and tried to win recognition from other countries. It is no coincidence that the Chinese Communist Party and the KPG got their starts in Shanghai. The presence of so many British, French, and American businessmen and diplomats gave the city a degree of freedom not available anywhere else in China.

Very close by was something I meant to see, but I somehow failed to do so. I speak of the residence of Sun Yat-Sen, founding father of the Republic of China in 1912. He died in 1925, but his widow was still there on September 20, 1966 when a group of Red Guards busted in and ransacked the house. They stole everything they could find and accused Mme. Sun (a card-carrying member of the Party) of living a luxurious life and harboring capitalist ideas.

I was hurrying down jam-packed Nanjing Road when I was accosted by a man wearing a Brigham Young University jacket. He called himself John and invited me to join him for coffee and conversation. I did not have much time, but I was agreeable. John took me several blocks in the opposite direction and upstairs to his chosen coffee shop. We talked, drank our Americanos and nibbled on nuts. Then, to my surprise, the waitress handed me the bill. Why me and not John? Although I was willing to pay, I was stunned to see the amount—440 yuan or roughly $70! Seventy bucks for coffee? I told John, truthfully, that I did not have that much money in my pocket. I took what I had, threw it on the table and headed out the door. Only later did I realize that John and the waitress were in cahoots and I had been scammed.

There was no time to lose because I was supposed to meet Cathy at the Monument to the People’s Heroes at the north end of the Bund. We got on the subway and went under the river to Pudong. At first, we wanted to go to the top of the 468-meter-high Oriental Pearl Tower but there was a wait of four hours to get in. (Crowds, huge crowds.) The building, which has been compared to a Flash Gordon rocket, is distinctive to say the least. We were unwilling to wait that long and so took Tommy’s advice and went to the nearby Shanghai World Financial Center, and rode an elevator to a coffee shop on the 87th floor. There we talked about Cathy’s work at Astor House, her education, her career plans and more. Unfortunately, dense fog was right outside so we could not see any of the panorama below.

I had enjoyed quite a bit of New Year’s music and dancing on television in my hotel room, and at midnight I was awakened by a surfeit of explosions. Fireworks were invented in 7th century China, you know. Actually, I had read in the China Daily that citizens were discouraged from setting off fireworks on their own. I had also seen many posters on walls around the city urging them to refrain. Obviously, not all did.

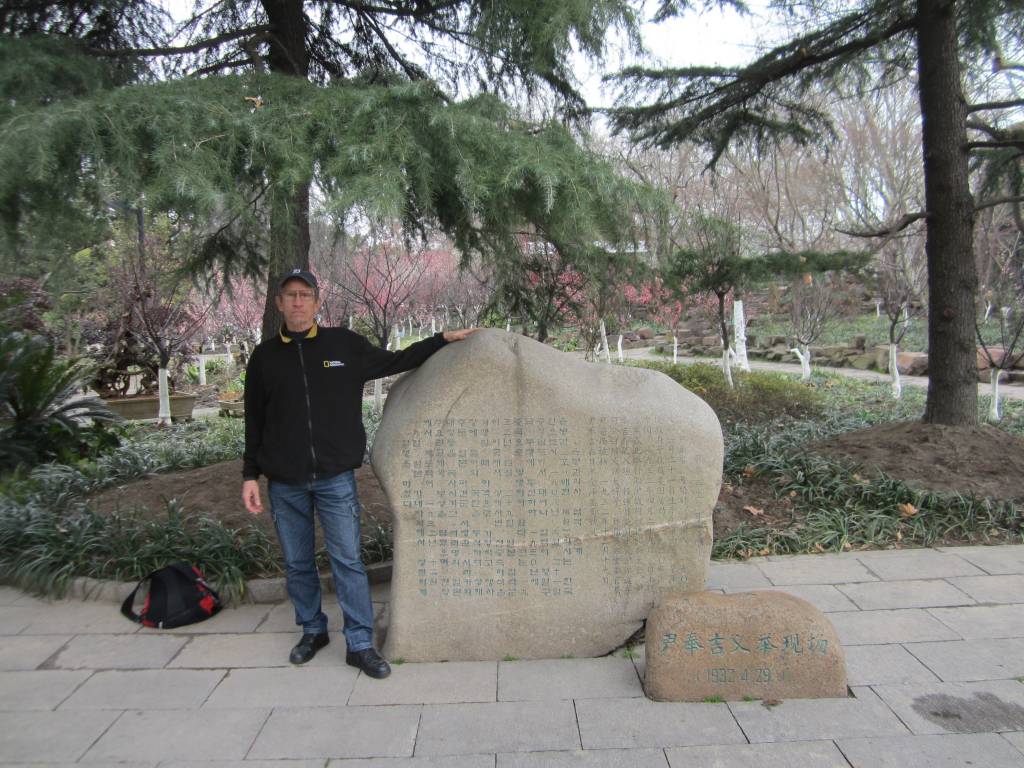

On my last full day in Shanghai, I had to visit what was formerly known as Hongkou Park. That is where, on April 29, 1932, Yoon Bong-Gil carried out a bombing attack that killed and injured some Japanese military and political leaders. Chiang Kai-Shek was pleased, saying, “A young Korean patriot has accomplished something tens of thousands of Chinese soldiers could not do.” Of course, there were repercussions beyond Yoon’s arrest and subsequent execution; the Japanese raided the above-mentioned office of the Korean Provisional Government, forcing it to move to Chongqing. There was a small museum inside the park and a marker beside which I posed for a photograph. About 30 years ago, Hongkou Park was renamed in honor of Lu Xun, a leftist writer with whom I was not familiar. His life spanned 1881−1936, and he had resided nearby. Outside the Lu Xun Museum was a gallery of statues of the world’s greatest writers—Dickens, Shakespeare, Balzac, Goethe, Gorky, Dante, Tolstoy, Tagore (who twice visited Shanghai), Pushkin and Hugo. The implication was clear that Lu belonged in that august group.

In Lu Xun Park, I saw people slow dancing and singing, sometimes in large groups. This charming scenario had been noted in my other two visits to China in 2010 (Beijing) and 2013 (Shenyang and Tonghua). It is not done in Korea for some reason.

I next traveled to the Zhabei district, which I wanted to see because it had suffered almost unimaginable destruction by the Japanese in 1937. With the passage of 80-plus years, Zhabei seems to have recovered but I would dearly like to have had an English-speaking native give me a quick tour and summary. I stopped in a park and saw a couple of adorable little girls bouncing on trampolines.

My visit to Shanghai nearing an end, that night I went back to Yuyuan Market and had an outdoor meal while sitting at a plastic table. As I did so, Middle Eastern music played. It reminded me vividly of being in sun-baked Cairo 22 years earlier.

On Tuesday morning, it was with some sadness that I checked out of Astor House and took a taxi to the nearest subway station. I had three hours before my flight left, so I stopped in Pudong, had coffee and watched a multitude of people pass by. I snapped some final photos and left. It was time for me to return to my life in Seoul.

Add Comment