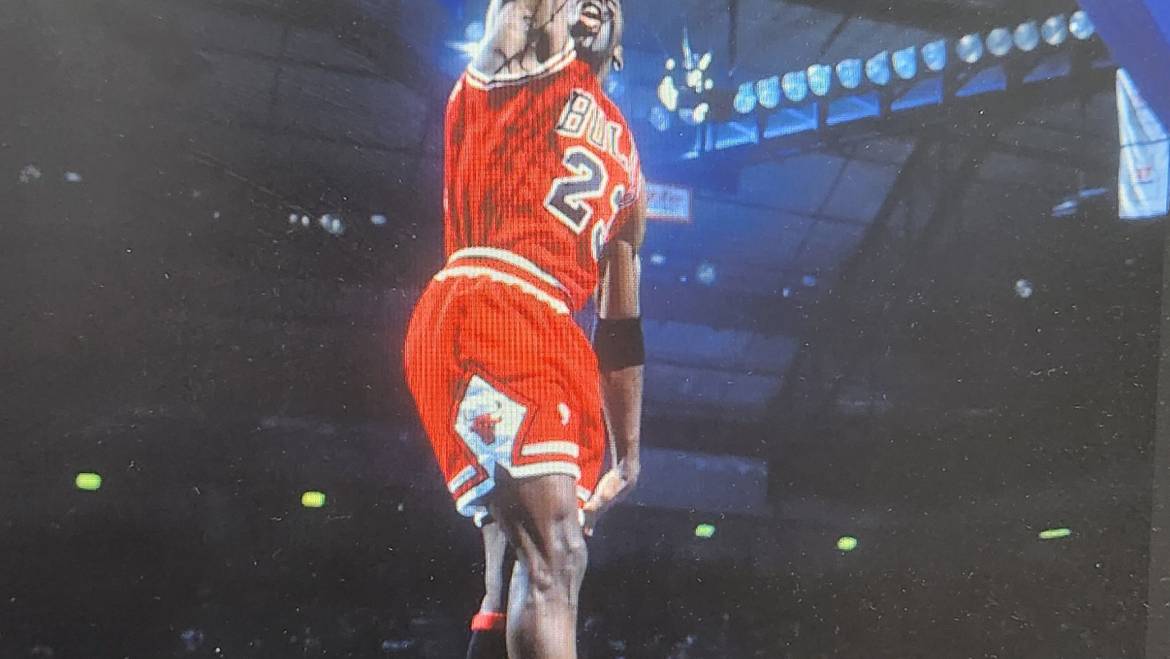

I have written elsewhere of my deep admiration for Michael Jeffrey Jordan. It started when, as a freshman at North Carolina, his picture-perfect jump shot beat Georgetown to win the 1982 national championship. Every inch a star with the Chicago Bulls, he earned six rings and five MVP awards. Coming out of retirement, he was a lion in winter during two seasons with the Washington Wizards. Jordan may have lost a step and did not jump quite as high as before, but he could still school guys in their 20s. Consider what he did on New Year’s Eve 2001: 45 points, 10 rebounds, 7 assists, and 3 steals against the New Jersey Nets, then the best team in the Eastern Conference.

I hesitate to tug on Superman’s cape, but he was far from perfect. First, there was the gambling. It was an open secret in the NBA that Jordan enjoyed going to casinos and rolling high. When he and his father took a limo from New York to Atlantic City to play poker, blackjack and badugi the night before Game 2 (which the Bulls lost) of the 1993 conference finals, people got up in arms. That was 32 years ago, and mores have changed. Nowadays, a team can get blown out in a big game and an hour later those players are making it rain on some strippers, and the media’s reaction is the colloquial interjection used to express indifference or boredom—“meh.”

Serving as general manager or part owner of the Wizards and the Charlotte Bobcats, Jordan has been heavily involved in drafting players, but his ability to assess athletic talent is rather poor. Here are some examples. High schooler Kwame Brown, whom he made the No. 1 pick in the 2001 draft, is widely considered one of the biggest busts in league history. Jordan took Adam Morrison of Gonzaga No. 3 in 2006, and the guy just could not play at the NBA level; he sat at the end of the bench for 161 games and was gone. In the 2014 draft, Jordan passed on Nikola Jokić—twice!—for a couple of players who never did anything, Noah Vonleh and Shabazz Napier. In 2018, Jordan took Shai Gilgeous-Alexander of Kentucky with the No. 11 pick (a smart choice in retrospect, as Gilgeous-Alexander was MVP and led the Oklahoma City Thunder to the league title in ’25) but then traded him to the LA Clippers for somebody named Miles Bridges. It is also important to remember how shabbily he treated Jerry Krause, Bulls GM from 1986 to 2003. Krause may have been a stumpy little guy, but he had a good sense for who could play and who could not. While nobody is right all the time, Krause chose more winners and fewer losers than Jordan.

Jordan had an imperious attitude toward teammates. That is, he poked and prodded and demanded the very best from all of them. One could say Jordan had the right since it was no more than he demanded of himself. Anything less, and he could be brutal if not cruel. Who could measure up, though, to Jordan, who was a very gifted athlete and ultracompetitive to boot? In a training camp scrimmage before the 1995 season, Jordan was talking trash to Steve Kerr, all but daring him to respond. Kerr, knowing his manhood was being challenged, did and got a black eye for his trouble. A similar thing happened with Will Perdue. Scott Burrell and Rodney McCray were such frequent targets of Jordan’s barbs that he may have hastened the end of their NBA careers. Stacey King, Horace Grant, Orlando Wooldridge and Craig Hodges are four more Bulls who were subjected to Jordan’s razor-sharp tongue. And he had a love-hate relationship with Scottie Pippen, a major contributor to those six titles in Chicago. It was a leadership style that left scars. Jordan’s aggressive—some would say tyrannical—approach may not have endeared him to his teammates, but then again professional basketball is not for limp-wristed, pantywaist boys.

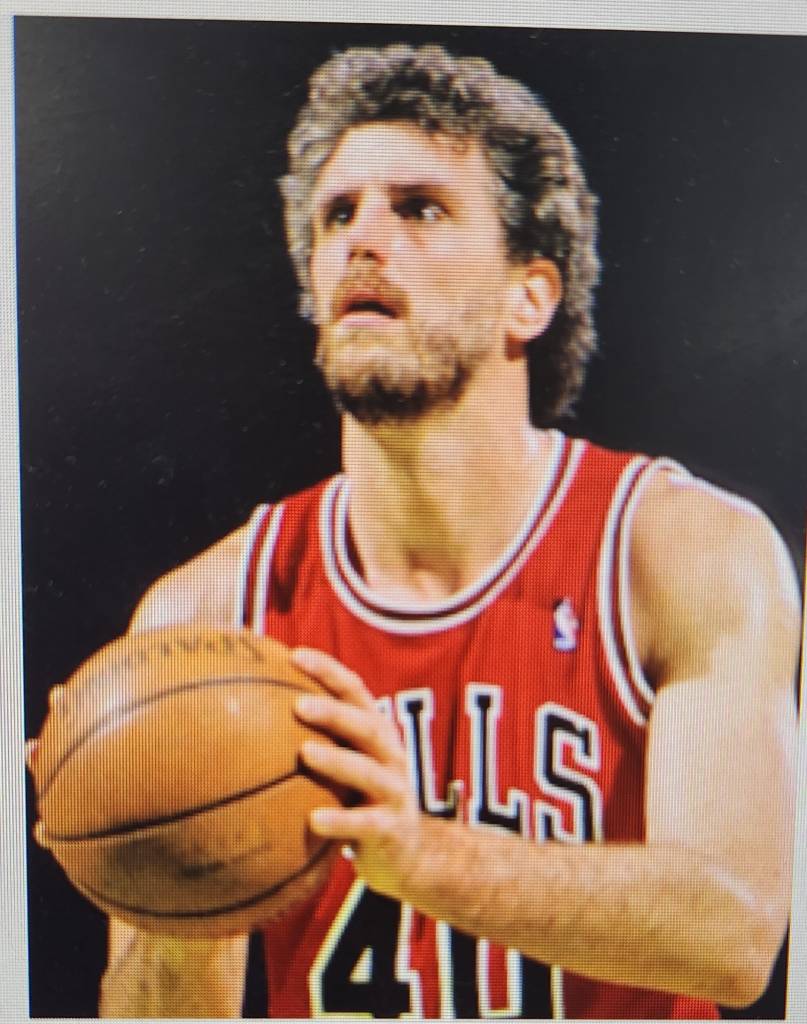

At least three of the Bulls refused to be intimidated. Jordan, NBA rookie of the year in 1985, had to miss most of the next season due to a broken foot. He came back determined to instill some toughness in a team sorely lacking it. In practice before a big game in 1987, he got into a tussle with Dave Corzine, whose burly physique and facial hair merited the nickname “Lumberjack.” Corzine initially let it go, but Jordan kept up the taunts. The dynamic having changed, Corzine charged the Bulls’ superstar. Jordan was grateful that four teammates held Corzine back.

During the 1988 season, Krause traded Charles Oakley—whose primary duty, besides defense and rebounding, had been to serve as an enforcer and to protect Jordan from cheap shots by opposing players—to the New York Knicks for Bill Cartwright, a center who stood four inches taller. Jordan made Cartwright’s life miserable, not hesitating to berate him during timeouts and even on the court as thousands observed. Cartwright, who had some pride, took offense. When he heard that Jordan had instructed the other Bulls not to pass him the ball, that was the last straw. He pulled Jordan aside and told him, “I don’t like what you’re saying to our teammates about me. If I hear you do it again, you’re never going to play basketball again because I will break both of your legs.”

Whether Cartwright would have followed through with such a bold threat, who knows? But Jordan got the message. Although Cartwright’s scoring and rebounding numbers are not off the charts, he surely did his part in the 1991, 1992 and 1993 championships.

In 1997, nearing the end of a distinguished 21-year NBA career that included three titles with the Boston Celtics, center Robert Parish signed with Chicago. He was, of course, aware of Jordan’s dictatorial tendencies. In a practice session before the season started, Jordan let him have it. “Michael has a tendency to test his teammates, especially the new faces on the team,” Parish told a Boston reporter in 2016. “And I think it was more of a test than a threat. He was just testing my reaction to his being a bully. And so I didn’t back down. He said he’d kick my butt, and I told him if he feels that strongly about it, come and get some.”

In act 5, scene 4 of Henry IV, Shakespeare has Falstaff aver, “discretion is the better part of valor.” In light of Parish’s invitation, Jordan came to much the same conclusion.

Jordan, as we have seen, was no angel. Nevertheless, it must be said that at the end of the day, he delivered. He lifted the Chicago franchise in which a culture of mediocrity was deeply engrained to six championships. Had he not been off playing minor league baseball in 1994 and 1995, I dare say that would have been eight. He pushed teammates—indeed everyone around him—out of their comfort zone and insisted on excellence. Michael Jordan was the ultimate alpha dog.

2 Comments

Excellent article. I knew some of this, but did not know he berated his own teammates. I thought he tried to encourage them to be the best.

Yes, great athletes don’t always turn out to be good at coaching or scouting for talent.

A side I did not know. Seems he could have used more assertive teammates. Of course most of the time nothing good awaits if Superman’s cape is pulled.

Add Comment