Eighty years ago yesterday, after the playing of Kimigayo (the Japanese national anthem) in a pre-recorded 4-minute and 36-second statement via the nation’s broadcasting company, Emperor Hirohito lamented that “the Empire’s efforts to liberate East Asia” had been unsuccessful. And, putting it rather lightly, he added that “the war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage.” While Hirohito never uttered the word “surrender” (kōfuku in Japanese), he acknowledged that he was ordering his political and military underlings to inform the governments of the United States, Great Britain, China and the Soviet Union that he accepted every provision of their joint declaration issued three weeks earlier at Potsdam, Germany. Formal surrender ceremonies (usually consisting of a mortified Japanese general bowing and handing over a sheathed sword) would soon take place on board the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, in Port Moresby, in Taipei, in Saigon, in Penang, in Baguio, in Labuan, in Rangoon, in Singapore, in Hong Kong and in Kuala Lumpur. World War II had come to an end, and the Japanese (along with their warmongering allies, the Nazis) had a lot of explaining and apologizing to do. Nobody deserved that more than the Koreans, who had suffered terribly during Japan’s heartless 36-year colonial rule.

When word came that Hirohito had conceded, there was jubilation all over Korea—from Baekdu Mountain in the north to Jeju Island in the south. But I would submit that the happiest people of all were those who had been unjustly held captive in Seoul’s Seodaemun Prison. This facility, now a tourist spot (drawing an estimated 700,000 visitors per year) not far from Gyeongbok Palace, has been preserved—as well it should be. Let us always keep alive the memory of what the Japanese did there.

When I moved from Daegu to Seoul in February 2009, my first excursion was not to Gwanghwamun Plaza, or the Blue House, or any of the five palaces, or Itaewon, or Cheongye Stream but to Seodaemun (pronounced “suh-day-moon,” by the way) Prison History Hall. I had read about it and had to see it for myself. Rather like the Demilitarized Zone, some people choose to stay away from Seodaemun, regarding it as gloomy or even frightening. Yesterday, Liberation Day in Korea, was my fifth visit.

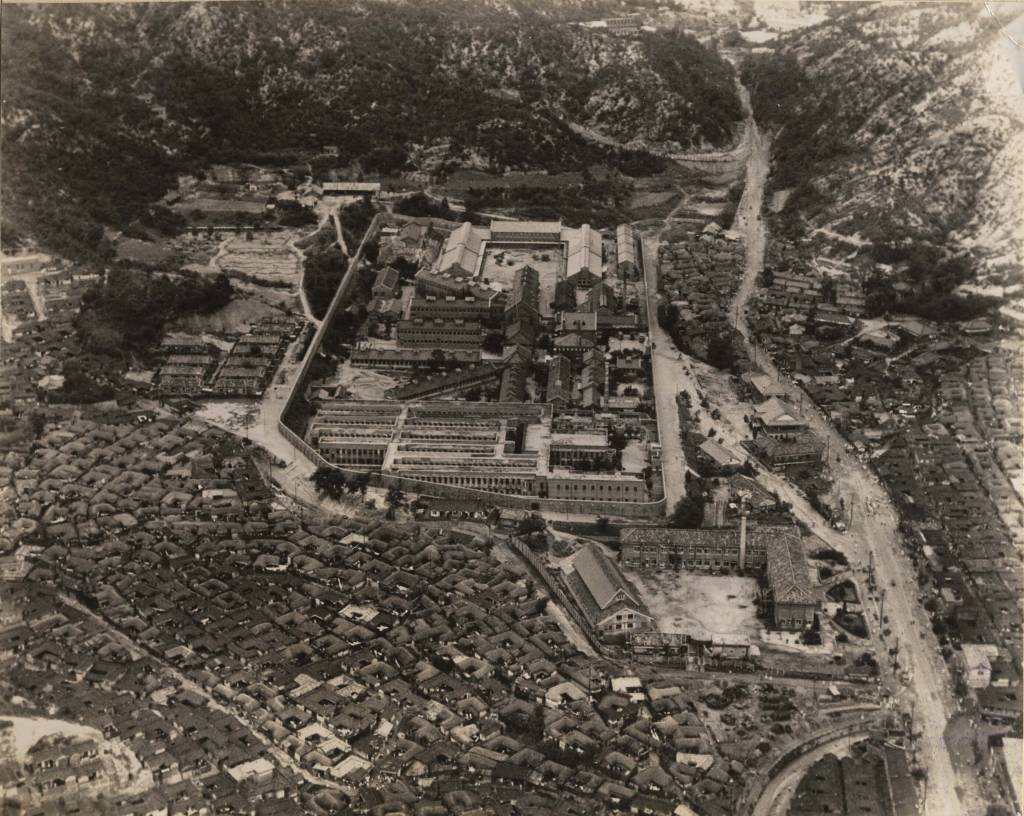

I will summarize its history. Opened in 1908—before the Japanese had formally annexed Korea—it originally held 500 inmates, but that mushroomed to 3,000 after the March 1, 1919 Independence Movement erupted. Seodaemun grew to 98 buildings for horribly overcrowded living quarters, work stations and punitive rooms. And don’t forget the death house, conveniently situated next to a hill so that people who had been hanged could be removed discreetly, not antagonizing Seoul citizens too much. Among other things, Seodaemun inmates were subjected to indoctrination in the Japan-centric worldview. Some of the more prominent Koreans who suffered under the Japanese at Seodaemun were Kim Gu, Ahn Chang-ho, Yoon Bong-gil, Han Yong-un, Lee Hyo-jeong, Yeo Un-hyeong, Park Jin-hong and Yu Gwan-sun.

Make no mistake—this was a grim place. I returned yesterday to honor Kim, Ahn, Yoon, Han, Lee, Yeo, Park, Yu et al. You might think that with the passage of eight decades I would be willing to let go of my anger at the damn J’s. After all, I am not even Korean! But that is the attitude I hold, and it does not seem to be changing. I know quite a few natives who profess to have forgiven and forgotten what was done to their ancestors by Hirohito’s men. I beg to disagree. What right did they have to come here, extract as much wealth as possible, abuse Korean females (you surely know of the so-called Comfort Women issue), purport to be superior and imprison, torture and kill with impunity?

In August 2015, Japanese Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama visited Seodaemun Prison History Hall, where he knelt and bowed before a memorial to Korean independence activists his countrymen had killed during those awful years—much as West German Chancellor Willy Brandt had done at a memorial to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising during a state visit to Poland in 1970. Hatoyama’s moment of genuflection and expression of remorse for the Japanese occupation of Korea was, I suppose, better than nothing.

By no means did Seodaemun Prison go out of business, so to speak, in August 1945. Its decommissioning came in late 1987 when all the inmates were transferred to the newly built Seoul Detention Center in Uiwang. During the Korean War, Kim Il-sung’s soldiers twice had control of the capital. They opened the gates to 8,500 prisoners (criminals, yes, but mostly people suspected of leaning left) and brought in an equal number who had dared to oppose them; the death house was busier than ever.

Whether the regimes of Syngman Rhee, Park Chung-hee and Chun Doo-hwan were dictatorial or merely authoritarian seems to be a matter of splitting hairs. But I will say that Korea’s road to social and political maturity was a rocky one, and that necessitated the continued use of Seodaemun Prison. Among the many people who served time there were Kim Dae-jung, Lee Myung-bak and Moon Jae-in, the 8th, 10th and 12th presidents of the Republic of Korea, respectively. It was Chun who finally decided to shut the ill-famed prison down, but his reasons were dubious. He sought to erase political excesses—of which Seodaemun Prison was a prime example—in the run-up to the 1988 Seoul Olympics. If Chun had had his way, the entire facility would have been razed and a park built there. (This is not unlike the debate in Dallas in the mid- and late 1960s about whether to keep the Texas School Book Depository, from which Lee Oswald killed President John F. Kennedy. Dallas Cowboys coach Tom Landry was among those who advocated tearing it down.)

I read the text of an interview done with Lee Jin-hee, the current director of Seodaemun Prison History Hall. She spoke eloquently about how Seodaemun was the site of heroic resistance in which Korean patriots were martyred at the hands of Japanese colonial officials, and that this must be remembered. But the position she holds forces her to downplay the fact that the prison was used for 32 more years after the fall of the Japanese Empire as a means to suppress political dissent. Lee might quietly agree with historian Russell Burge. In his 2017 article “The Prison and the Post-colony: Contested Memory and the Museumification of Seodaemun Prison” in The Journal of Korean Studies, he wrote, “Seodaemun Prison’s transformation into a site of colonial tourism…was carried out as part of a larger move in urban planning to overwrite the memory of the post-colonial authoritarian past, a process that reveals much about the limitations and contradictions of South Korean democratization.”

Seodaemun Prison History Hall, August 15, 2025…

2 Comments

Great article. Plenty of ugly history. Man is evil. How evil depends on who is in charge.

It is so hard to believe that people can be so cruel to another human being. Like the Holocaust for one. Different times, different beliefs.

Sorry for taking so long to get back. Been in Colorado, no internet and bad reception.

Add Comment