Eight years before he became commissioner of the National Football League, Pete Rozelle served as a public relations specialist for the Los Angeles Rams. A PR guy is not a scout, and yet he somehow found the ultimate diamond in the rough when he spotted a big—very big—and mobile offensive end playing on the team representing Camp Pendleton, the San Diego–area Marine base. Rozelle passed on this tip to the Rams’ main scout, Eddie Kotal. He, too, was impressed.

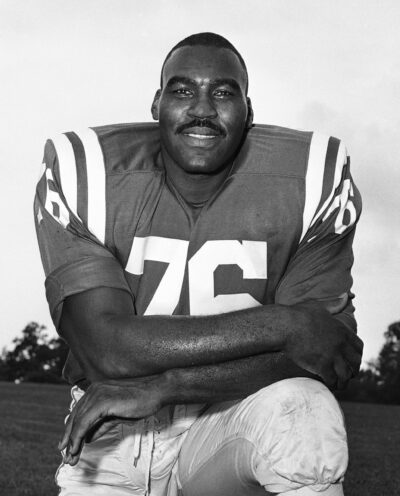

Eugene “Big Daddy” Lipscomb signed a free agent contract with the Rams the moment his hitch was up, joining the team for its final two games of the 1953 season. It was the beginning of an unlikely 10-year career in the NFL with three franchises that included two championships, two All-Pro selections and considerable notoriety. Moved to defense, Lipscomb, 6′ 6″ and 300 pounds with a seven-foot wingspan, could occupy multiple offensive linemen and was fast enough to chase ball carriers from sideline to sideline. The nickname derived from his inability to remember names, instead calling virtually every man he encountered “Little Daddy.” So he was “Big Daddy.”

Born in 1931 in Uniontown, Alabama to a family of cotton pickers, he and his mother, Carrie, moved to Detroit when he was three. This was soon after his father, whom he never knew, died. Eight years later, a soul-scarring incident occurred. Carrie was murdered, stabbed 47 times by her boyfriend; Lipscomb carried the homicide photos with him for the rest of his life. He went to live with his maternal grandparents, but they were none too kind, insisting that he buy his own clothes and pay rent. His grandfather verbally and physically abused him. Once, caught stealing a bottle of whiskey—he was later known to average two fifths a day—he was stripped naked, tied to a bed and beaten. Lipscomb set pins in a bowling alley, washed dishes, loaded trucks and worked in a junkyard in his youth, but that’s not all. One year, he ran a forklift in a steel mill from midnight to 7 a.m., changed clothes and then went to school.

Despite being functionally illiterate (he could scrawl his name, just barely), a college scholarship was a possibility for this football and basketball star at Detroit’s Sidney Miller High School. But when it was determined that he had played semipro hoops, Lipscomb was ruled ineligible to compete during his senior year. His coach advised him to join the Marines, which led him to Camp Pendleton and his meetings with Pete Rozelle and Eddie Kotal.

After two full seasons with LA, Lipscomb ran into trouble. He sometimes showed up at team meetings hung over and fell asleep. Furthermore, his tendency to freelance irritated Rams coach Sid Gillman who liked disciplined players. “Disciplined” is an adjective seldom applied to Big Daddy Lipscomb—whether on or off the field. In a 1956 preseason game against the Baltimore Colts, he made a late hit on quarterback Johnny Unitas, sparking a brawl. Gillman had seen enough and cut him. But Colts coach Weeb Ewbank was willing to let bygones be bygones and signed him, setting the stage for Lipscomb to reach the heights. He was a major contributor to Baltimore’s 1958 and 1959 NFL championships, the former of which culminated with the so-called greatest game ever played: a 23-17 sudden-death overtime defeat of the New York Giants.

(It was this dramatic contest—seen on television by 45 million people—that stimulated the sudden rise in the popularity of pro football and caused Lamar Hunt to go about forming the American Football League. Lipscomb, along with his teammates, got $4,178 for his efforts.)

The NFL was full of Big Daddy anecdotes from those days, and here is an example. When Forrest Gregg was a rookie with the Green Bay Packers, he found himself overmatched by the Colts’ mountainous number 76. So he did what any self-respecting offensive lineman would do by holding him. Lipscomb was displeased and said to him, “Hey, Forrest. Let’s make a deal. If you don’t hold me, I won’t kill you.”

With the Rams, the Colts and later the Pittsburgh Steelers, Big Daddy was a tough customer. And yet he was a good sport, often extending a helping hand—albeit one the size of an iron skillet—to an opponent he had knocked to the ground. Teammates, all of whom had spent four years in college, regarded him with equal measures of fear and scorn. As indicated earlier, he could not read, and many of the people he hung out with were considered hustlers, hoodlums and bad actors, so he slept with a gun under his pillow. There were three broken marriages, one case of bigamy and child-support payments not made. Unable to control his impulses, he was said to seek intimacy with almost every woman he met. A two-fisted drinker and a troubled man, he gambled, tore up hotel rooms and sometimes inexplicably burst into tears. Nevertheless, Lipscomb, whose top NFL salary was $14,000, was known to be generous to poor kids he came across.

The 1962 season was one of his best. He started 13 of 14 games for the Steelers and made the Pro Bowl for a fourth time. Since Lipscomb was just 31, there was no reason to think he would not sustain it for a while longer. But on the night of May 9, 1963, he and a man named Tim Black went out prowling the streets of Baltimore. In his yellow Caddy, they cruised from one joint to another. They met some women, retired to Black’s seedy apartment, drank and partook of heroin until 3 a.m. Lipscomb fell into a sleep from which his companions could not wake him. They called an ambulance, but he was dead on arrival at Lutheran Hospital. Some friends were skeptical of the heroin charge, saying Big Daddy was afraid of needles and never spoke about drugs. They suggest that Black had injected the stuff into his right arm, hoping to incapacitate him enough to steal the cash he always carried.

His funeral was held in Detroit, as a crowd of more than 1,000 people—teammates, loved ones, fans and the curious—attended. His pall bearers were guys he had played with: Erich Barnes, Luke Owens, Jim Parker, Sherman Plunkett, Johnny Sample, Dick “Night Train” Lane, John Henry Johnson and Lenny Moore. Since Lipscomb’s death took place under murky conditions, some Hall of Fame voters may have let that influence them when he was up for election. His only chance at this point is the Veterans Committee, and he does have his advocates.

I will add that John Bridgers, the Baltimore Colts’ defensive line coach when Lipscomb wore the horseshoe, regarded him as the best of that era at his position. Big and swift, he was a prototype of the modern defensive lineman.

Finally, a few lines from Randall Jarrell’s rhapsodic poem “Say Good-bye to Big Daddy”:

Don’t weep for me, Big Daddy,

Don’t bother with no prayer;

I don’t want to go to heaven

Unless they swing up there.

Don’t take me up to heaven, please Lawd,

‘Less there’s kicks and chicks up there.

4 Comments

Wow. Well worth your time. I remember him, but that is in name only. I was an early Cowboys fan. One cannot forget a name like Big Daddy Lipscomb. With his size he had to be one of the biggest men on the field.

That $14,000 salary was large for those days. That $4,000 bonus was also a sizeable down payment for a nice Cadillac convertible in 1960. Another $2,000 got you down the road in style.

Oh, he was usually (always?) the biggest. I doubt Big Daddy used his $4,178 bonus wisely.

He would have appeared thrice at the Cotton Bowl–with the Colts in 1960 and the Steelers in 1961 and 1962.

I knew his name as he was before my time but I knew nothing of his real story. Great article Richard

It’s entirely possible that he and Abner Haynes crossed paths at some point. I respect both.

Add Comment