Former NBA players blowing through their money and ending up broke and in desperate straits is an oft-repeated story. Shawn Kemp, Vin Baker, Latrell Sprewell, Antoine Walker, Rumeal Robinson, Derrick Coleman, Larry Johnson, Christian Laettner, Glen Rice, Kenny Anderson, Darius Miles and Allen Iverson are just a few. Poor financial decisions, gambling, drugs and booze, falling victim to investment scams, child support for baby mamas, failure to pay taxes and supporting a large “posse” are some of the factors that contributed to the downfall of these gentlemen, none of whom earned less than $61 million in hoops careers of varying lengths. (Consider what the top guys get nowadays: Jayson Tatum and Jaylen Brown of the Boston Celtics, Nikola Jokić of the Denver Nuggets, Bradley Beal of the Washington Wizards and Anthony Edwards of the Minnesota Timberwolves are all operating on 5-year deals worth more than $250 million—truly obscene numbers.)

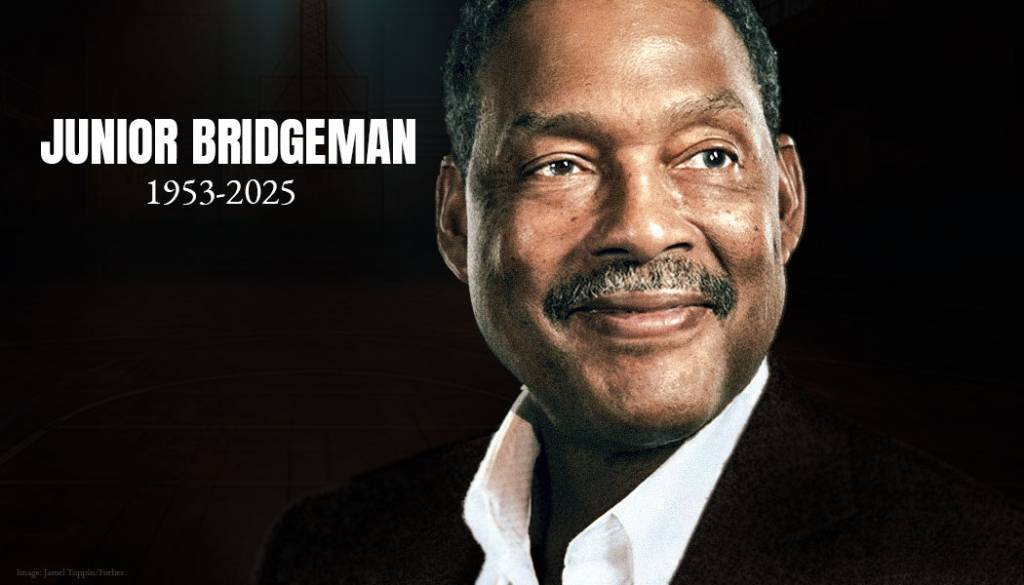

By contrast, there is a man who spent 12 seasons (1976–1987) in the league and earned just $2.95 million, topping out at a salary of $350,000. But nobody ever had to throw a pity-party for Ulysses Lee “Junior” Bridgeman. He was worth an estimated $1.4 billion when he died, aged 71, earlier this month. I propose to traverse his athletic and business achievements in the ensuing paragraphs.

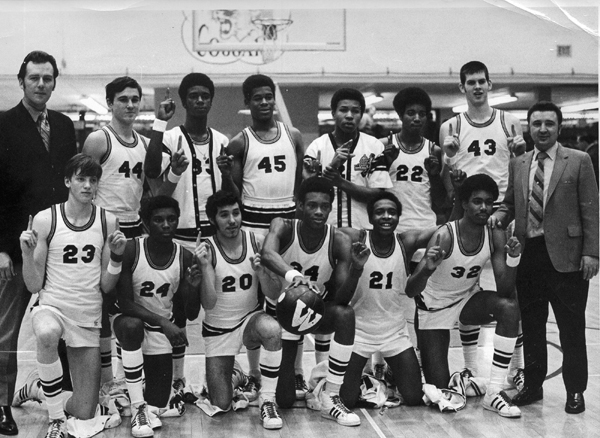

The younger of two brothers, he was born in East Chicago, Indiana on September 17, 1953. Bridgeman’s father was a steelworker who swept floors and washed windows part-time, and mom was a homemaker; this was a church-going, blue-collar black family that emphasized work, education, humility and perseverance. Whether his parents were sports-minded, I do not know. But his brother, Sam, got a basketball scholarship to the University of Denver, earned two degrees and had a long, successful career in the insurance business. Bridgeman was a member of what was then considered one of the best high school teams ever, the 1971 East Washington Senators. Beating their opponents by an average of 30 points per game, they went 29-0 and rolled to the Indiana state title. What makes that team even more special is that three members—Bridgeman (Louisville), Pete Trgovich (UCLA) and Tim Stoddard (North Carolina State)—would play at least once in the NCAA Final Four in 1973, 1974 and 1975.

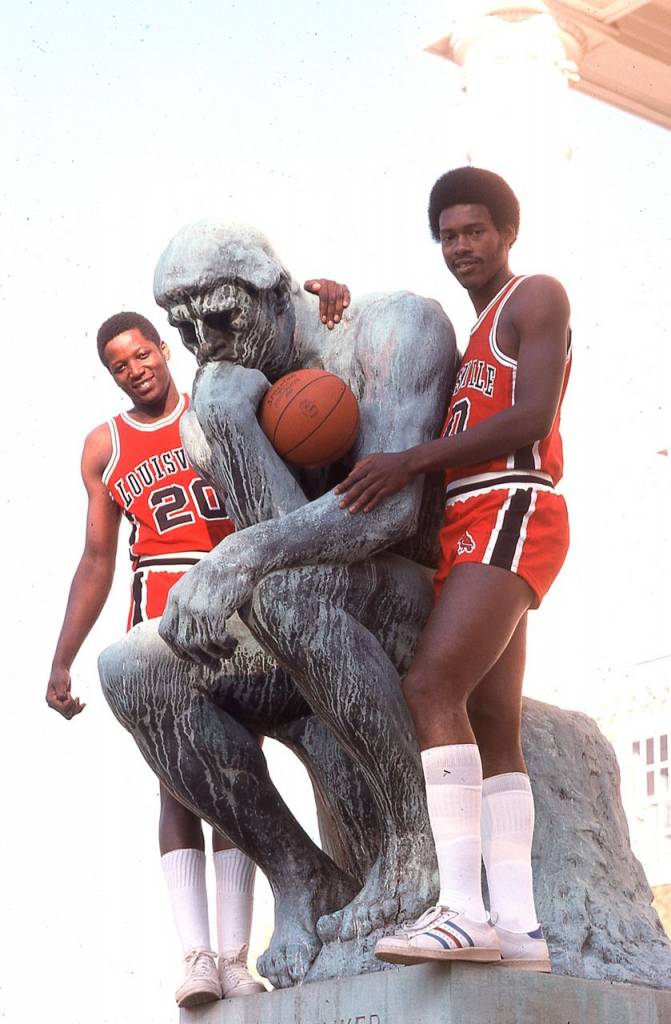

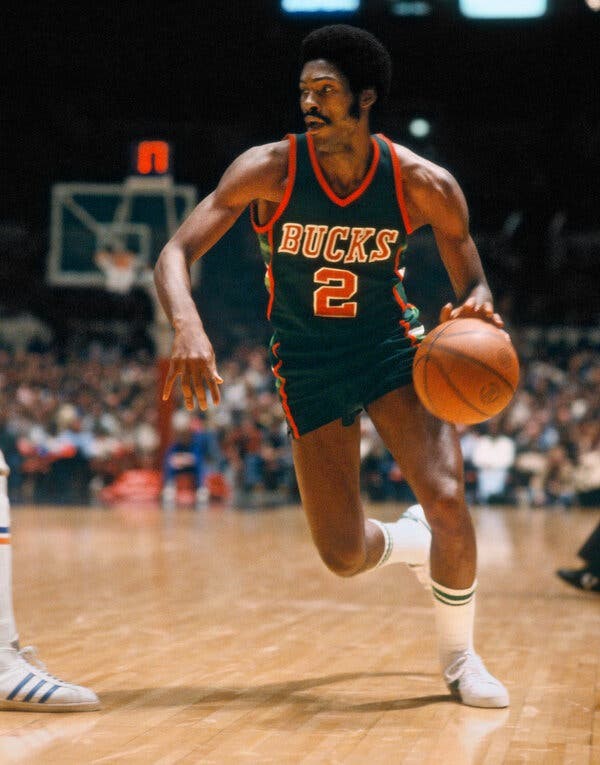

Coach Denny Crum, who had gotten to Louisville just a year earlier, convinced Bridgeman to come downstate, and it was a good match. In his three varsity seasons, the Cardinals went 72-17. He averaged 15 points, 8 rebounds and 3 assists per game and was twice Missouri Valley Conference player of the year. Standing 6′ 5″ and capable of playing both the guard and forward positions, he was taken in the first round of the 1975 NBA draft by the Los Angeles Lakers and soon traded to the Milwaukee Bucks. Bridgeman spent a decade with the Bucks (and two seasons with the LA Clippers). Playing alongside Sidney Moncrief, Marques Johnson and Bob Lanier, he helped them win division titles every year from 1980 to 1984. Usually a sixth man—he started only 52 of the 849 pro games in which he played—he was a fine athlete and a very competent hoopster. Magic Johnson said Bridgeman “had one of the sweetest jump shots in the NBA.”

Possessor of a bachelor’s degree in psychology from UL, he realized early in his career that the paychecks would eventually stop coming, and then what? Bridgeman had a discussion with then-Bucks owner Jim Fitzgerald. Chairman of the NBA’s television committee, he suggested that Bridgeman invest in his new cable TV business. Bridgeman did a thorough risk assessment before borrowing $150,000 from a Milwaukee bank and turning that over to Fitzgerald. Within a few years, its value had more than quadrupled.

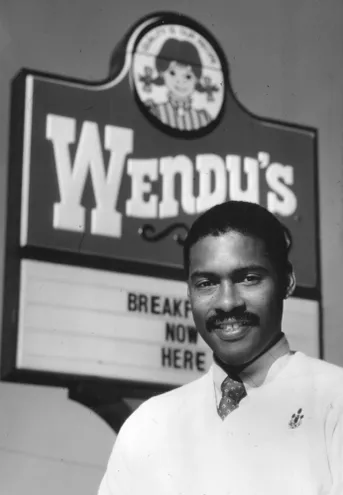

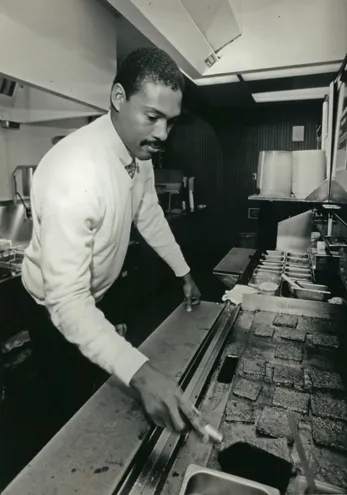

He knew that Wayne Embry, the Bucks’ general manager and himself a former player, owned several McDonalds’ franchises, so he bought a Wendy’s outlet in Brooklyn. It failed to make a profit. Bridgeman, undeterred, decided to attend a Wendy’s training school to learn the business from the ground up. A $750,000 investment in 1988 (the same year his jersey number, 2, was retired by the Bucks) brought him five Wendy’s restaurants in the Milwaukee area. You talk about a hands-on owner—Junior Bridgeman thought nothing of making fries, flipping burgers, washing dishes, mopping floors and serving customers at the drive-in window.

In time, he had a portfolio of more than 500 Wendy’s, Chili’s and Pizza Hut franchises. He sold most of them in 2016 for an estimated $250 million and used the proceeds to become a Coca-Cola bottler and distributor in Kansas, Missouri and southern Illinois. It was one entrepreneurial success after another as he became part-owner of the Bucks, bought Ebony and Jet magazines (both of which document black culture) and joined or founded other companies throughout the United States and Canada.

His wife Doris, and children Justin, Ryan and Eden, all of whom have MBAs, were (and still are) active in the business and together they formed a foundation that quietly sponsors or joins in a number of philanthropic ventures, primarily in Milwaukee and Louisville. Acutely aware of pro athletes whose lives had gone bad after the cheering stopped, he often spoke to subsequent generations of NBA players, emphasizing the need for financial literacy, wise stewardship of wealth, investing, and the ability to structure a loan, handle accounting and deal with the IRS. Most of all, he preached caution. “Money can disappear,” he said in an ESPN interview. “Whether it’s $80,000 or $80 million, it can still disappear on you.”

On March 11, Bridgeman was at the Galt House Hotel in downtown Louisville talking to a television reporter as part of a charity event. Despite having no major health problems, he suffered a heart attack and died soon after being rushed to a local hospital. The tributes to this hard-working visionary began pouring in from the sports world, from the business world and from people both black and White who had been blessed to cross his path.

2 Comments

Well worthwhile writing. Great subject. Junior took his chances and learned from each.

$350,000 makes me think he needed an agent, though. Great 6th men are rare.

I wish I had been more attentive during his career. I was a longtime Mavericks season ticket holder, so I undoubtedly saw him play.

Another example of the difference a strong family and quality coaching can make in a person’s life.

You continue to bring the unheralded greats of sports to my awareness. His story applies universally to the American dream. Similar to sports money, many financially favored professions lack the necessary practical education and self discipline to survive to the end line. Decisions are made assuming perpetual income. His life experiences teach principles for all of us. The parable of the talents. Not how much you start with rather what did you do with it. Thanks again for another uplifting historical hidden gem.

Add Comment