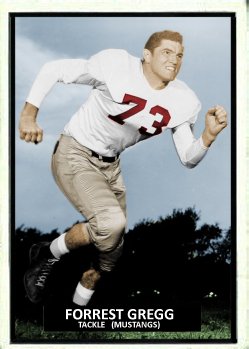

Two years after a pay-for-play scandal that caused Southern Methodist University to sit on the sidelines and ponder its misdeeds, the Mustangs were returning to the college football scene. Many of the players in 1989 and subsequent seasons would be genuine student-athletes: walk-ons and carefully recruited young men eager to represent the school on the gridiron. Not blue-chippers. Who, though, would coach them? SMU acting athletic director Dudley Parker and acting president William Stallcup (their predecessors had resigned in disgrace) convinced Hall of Fame offensive lineman Forrest Gregg to leave his job as head coach of the Green Bay Packers, take a salary cut and return to his alma mater in Dallas. A dominant two-way player for the Ponies between 1953 and 1955, he labored under impossible circumstances; the team went 3-19 in his two seasons. Gregg handed the coaching reins to another man and served as AD until 1994.

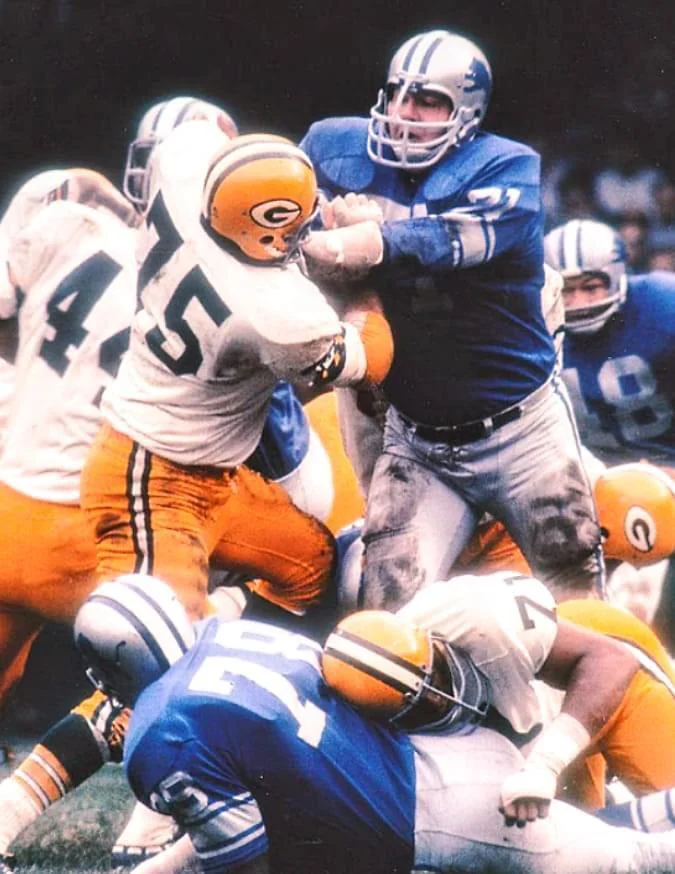

In the spring of 1989, the red-and-blue game consisted of the guys who would be on the team that fall versus some recently graduated Mustangs. I was there thanks to an invitation from Jerry LeVias, a letterman from 1966 to 1968. I got to talk to Raymond Berry (coach of the alumni), and although I did not meet Gregg, I was in his vicinity. I saw a big, friendly man who could—if necessary—be intimidating. This 6′ 4”, 250-pound offensive lineman played in 188 consecutive games for the Packers and Dallas Cowboys from 1956 to 1971, earning six championships. Seven times All-Pro, he had dealt with such opponents as Gene “Big Daddy” Lipscomb, Doug Atkins, Alex Karras, Deacon Jones, Bob Lilly, Carl Eller and Bubba Smith. Vince Lombardi is supposed to have called Gregg “the finest player I ever coached,” a rare accolade for an offensive lineman. I read of an incident from 1965 in which Lombardi stormed into the locker room after the Packers were upset by the Los Angeles Rams. Addressing his players, he stated that he was the only man present who cared about winning. Gregg rose, refuted that assertion and offered to whup Lombardi right then and there. Two teammates held Gregg back and prevented him from following through on his ill-advised threat.

Gregg was the Packers’ head coach for four seasons, preceded by four with the Cincinnati Bengals and three with the Cleveland Browns. His record of 75-85-1 is not too impressive, and he had his critics. The personification of a pro football warrior, Gregg looked like he was cast out of iron. Having won so much with Lombardi (and one more Super Bowl as a substitute in 1971 with Tom Landry), he had all the credentials any coach could want.

“Forrest was, in the eyes of the players, a no-nonsense disciplinarian,” said Bengals owner and president Mike Brown. “We happened to be personal friends away from football. And Forrest has a heart as big as an elephant’s. He’s a softy at heart. A wonderful guy. I’m deeply fond of him. But around the players, they weren’t sure. They jumped when he said ‘boo.’”

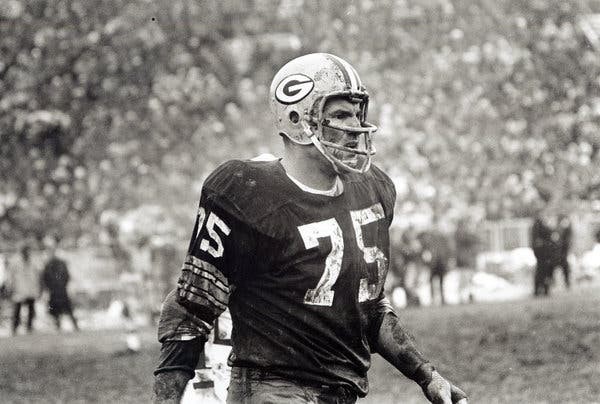

Here I take a close look at one game in his playing career and one in his coaching career. Both playoff games, they have long since passed into NFL lore: The Ice Bowl of December 31, 1967 at Lambeau Field against the Cowboys and the Freezer Bowl of January 10, 1982 at Riverfront Stadium against the San Diego Chargers.

In a first step to reach Super Bowl 2, Green Bay had beaten LA 28-7 at Milwaukee County Stadium and Dallas had administered a 52-14 drubbing of Cleveland at the Cotton Bowl. The Packers were back home for this one, and the conditions were atrocious: −13° Fahrenheit with a −48° wind chill factor. Brief consideration was given to postponing the game, but the players, coaches, fans, media and popcorn vendors all toughed it out. A rematch from the previous season in which the Pack won a tight game in Dallas, 18 future Hall of Famers took part in this historic game on Green Bay’s frozen tundra.

The Cowboys led 17-14 when the Packers took possession at their own 32-yard line. Just under five minutes were left. Quarterback Bart Starr and running backs Chuck Mercein and Donny Anderson methodically moved the ball toward the goal line in the stadium’s south end. Inside the Dallas 1-yard line, with 16 seconds left and no timeouts, Starr followed Gregg, Ken Bowman and Jerry Kramer into the end zone. (I have never understood why Kramer gets the lion’s share of credit for opening that hole in the Dallas defensive line.)

The Cowboys’ season was over; wide receiver Lance Rentzel later said that on the way back to Dallas’ Love Field, “not one word was spoken the entire flight.” The Packers, despite several players getting frostbitten fingers, had their way with the Oakland Raiders 33-14 two weeks later at the Orange Bowl.

Let’s fast forward 15 years. The Bengals were a team in disarray when Gregg took over. By his second season in Cincy, things had changed, and I refer not just to the outré tiger-striped helmets, jerseys and pants. After going 12-4 and beating the Buffalo Bills at home in 50-degree weather, Gregg’s team hosted San Diego; the Chargers were coming off an epic 41-38 overtime defeat of Don Shula’s Dolphins in Miami. When the teams met in Cincinnati, the temperature was −9°, but a sustained wind of 27 miles per hour made for an equivalent of −59°. I see no reason to quibble about which of these two games was colder, as both were miserably, almost unbearably cold.

Cincinnati had dominated San Diego 40-17 at Jack Murphy Stadium during the regular season, and here it was more of the same. As quarterback Ken Anderson completed 14 of 22 passes for 161 yards and no interceptions—he also ran for 39 yards—the Bengals earned their stripes 27-7. In Super Bowl 16 two weeks later at the Pontiac Silverdome, the San Francisco 49ers took the Lombardi Trophy with a 26-21 victory. One more thing about this bitter cold game on the banks of the Ohio River between the Bengals and Chargers—Anderson and San Diego tight end Kellen Winslow and QB Dan Fouts said they felt the effects of it in their fingers and toes decades later. And another—Gregg had been carried off the field on the shoulders of several of his admiring and jubilant players.

In 2019, Gregg died in Colorado Springs from complications of Parkinson’s disease—possibly resulting from the numerous concussions he suffered during his more than two decades of playing football. Seven years before his death, in an interview with the New York Times he reflected on his fabled career. Gregg’s fondest memory was not of reaching the mountaintop with the Packers, the Cowboys and (almost) the Bengals. It was of the underweight and overmatched guys who suited up for him at SMU in 1989 and 1990. “I never coached a group of kids that had more courage,” he said. “They thought that they could play with anyone. They were quality people. It was one of the most pleasurable experiences in my football life.”

3 Comments

Another great look back at the people behind the sport. I appreciate his perspective that the best memories are not the pinnacle achievements rather the people who give the most of themselves for their teammates.

Great article Richard I had the pleasure of meeting forest at the Marriott on stemmons when I went to have lunch with a fraternity brother of mine from East Texas State who was quarterbacking the Cleveland browns in the strike year I’m sure you remember that I sat down at the table with my friend and Forrest Greg and I couldn’t help but see the ring on Forest Greg’s hand it was his cowboys super bowl ring I asked him if I could try it on and I can tell you to this day I could put two fingers in that ring so he was a great guy I really had a good time that day talking with him about the cowboys and Packers and such you know as well as I do The cowboys and the Packers were better rivals back in our days in high school so it was a pleasure to get to sit and have lunch with him Great article again Richard

I did not know that Forrest Gregg played for the Cowboys, or coached SMU, or coached the Bengals. I remember him like it was yesterday.

What I do know is that pro football was a pure sport at that time. The guys were making nothing, they were playing hurt, they were sacrificing future health, and more.

They played because they wanted to play. I think if you are making $6, $8, $15 million a year, there may be other reasons.

If you ever want to do something on Norm Bulaich let me know. He is still around and still doing well. He’s playing these days at 175 lbs.

Add Comment