Just northeast of the Loveland Ski Area in Colorado is 12,477-foot-high Mount Trelease. On its lower flanks are the carefully preserved ruins of an airplane crash that occurred nearly 55 years ago. Many people have made the trek to that spot to remember, to meditate and to show respect for those who died. I will summarize for you what happened.

* * *

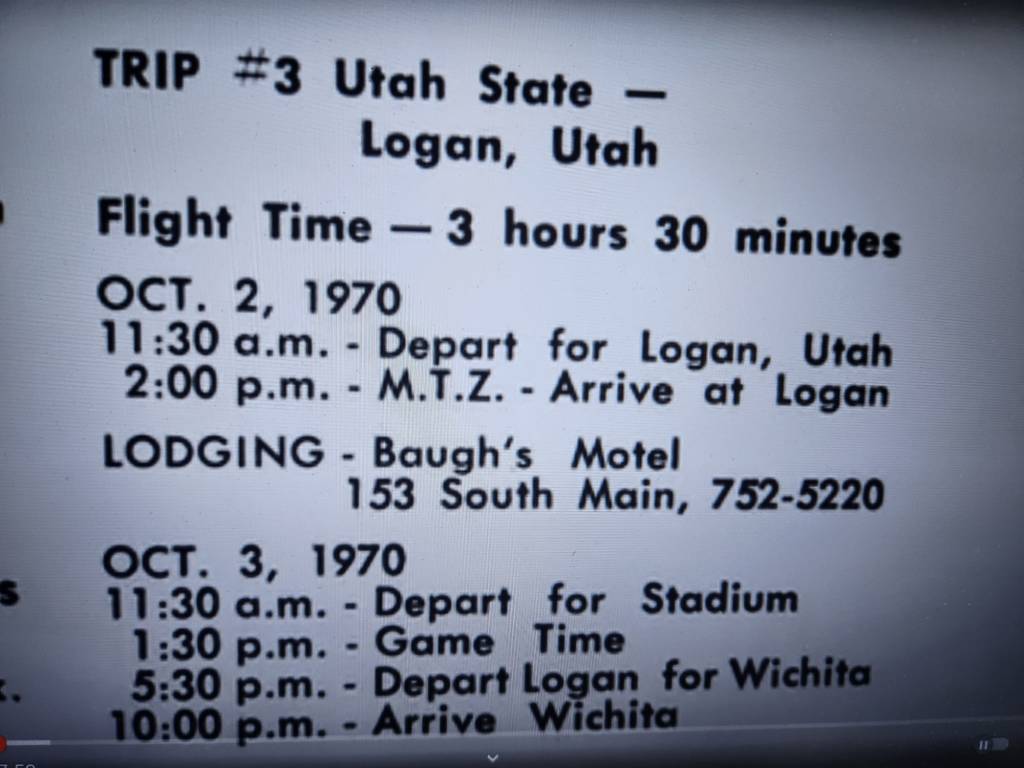

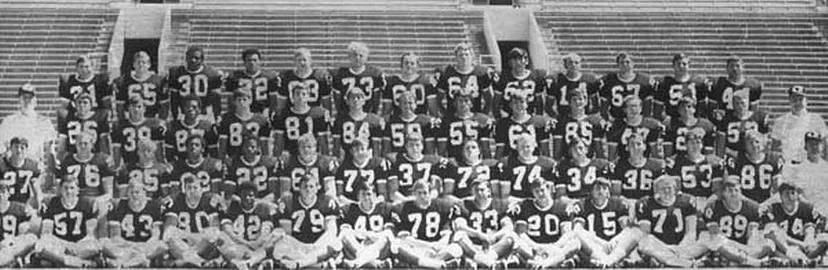

Prospects for the 1970 Wichita State University football team were not especially good. The Shockers, part of the Missouri Valley Conference, had won just 12 games in the previous five seasons. And so far, things were going poorly for coach Ben Wilson’s squad: losses of 41-14 to Texas A&M, 53-14 to Arkansas State and 43-0 to West Texas State. Maybe the result would be better when they took on Utah State in Logan on October 3. For out-of-town games, athletic director Bert Katzenmeyer had arranged an ill-fated deal with Oklahoma City-based Golden Eagle Aviation and its subsidiary, Jack Richards Aircraft Company. The eponymous owner of the latter entity offered a pair of Martin 404 propeller-driven airplanes which would be dubbed “Gold” and “Black”—the school’s colors—respectively.

The planes were identical in every way, but the 40 passengers each transported were not. “Gold” (Ronald G. Skipper [president of Golden Eagle Aviation] and Danny Crocker in the cockpit) carried most of the starting players, Wilson, Katzenmeyer, administrators, boosters and other family members. Riding in “Black” (Leland Everett and Ralph Hill) were reserves, assistant coaches and various support personnel. They took off from Wichita Mid-Continent Airport on the morning of Friday, October 2 and flew without incident to Denver’s Stapleton Airport for refueling. During that initial leg, Skipper had briefly turned over controls to Crocker and visited passengers in the cabin. He informed them that, unlike “Black,” “Gold” would not follow the original flight plan in the second leg, which involved going to southern Wyoming and then further west; they would take a more direct and scenic route over Loveland Ski Area and Mount Sniktau (the proposed alpine skiing venues for the 1976 Winter Olympics, which Denver would host), the continental divide and other points of interest. Lacking an aeronautical chart of the new route, Skipper excused himself during refueling and went inside the airport terminal to buy one.

The airway followed by pilots Everett and Hill in “Black” may have been prosaic by comparison, but it allowed planes enough time to gain altitude for the climb over the Rocky Mountains. Amid clear skies, they made it to Logan at 2 p.m. and then began a long and increasingly suspenseful wait for the other aircraft. With fuel, passengers and gear, “Gold” was about 2,600 pounds overweight. It had lumbered down the runway at Stapleton before finally getting airborne. Treating the flight like a sightseeing tour, Skipper soon powered down the engines and maneuvered into Clear Creek Valley. As two stewardesses handed out sandwiches, potato chips and apples, WSU players and others gazed out the windows at the scenery—some of which was remarkably close. Witnesses at high-altitude locations had the strange experience of looking down at a flying passenger airplane. Less than 30 minutes into the flight, some of those on board were becoming unsettled. One player, offensive lineman Rick Stephens, walked up the aisle to the cockpit only to find Skipper and Crocker frantically studying the map that had been purchased back in Denver.

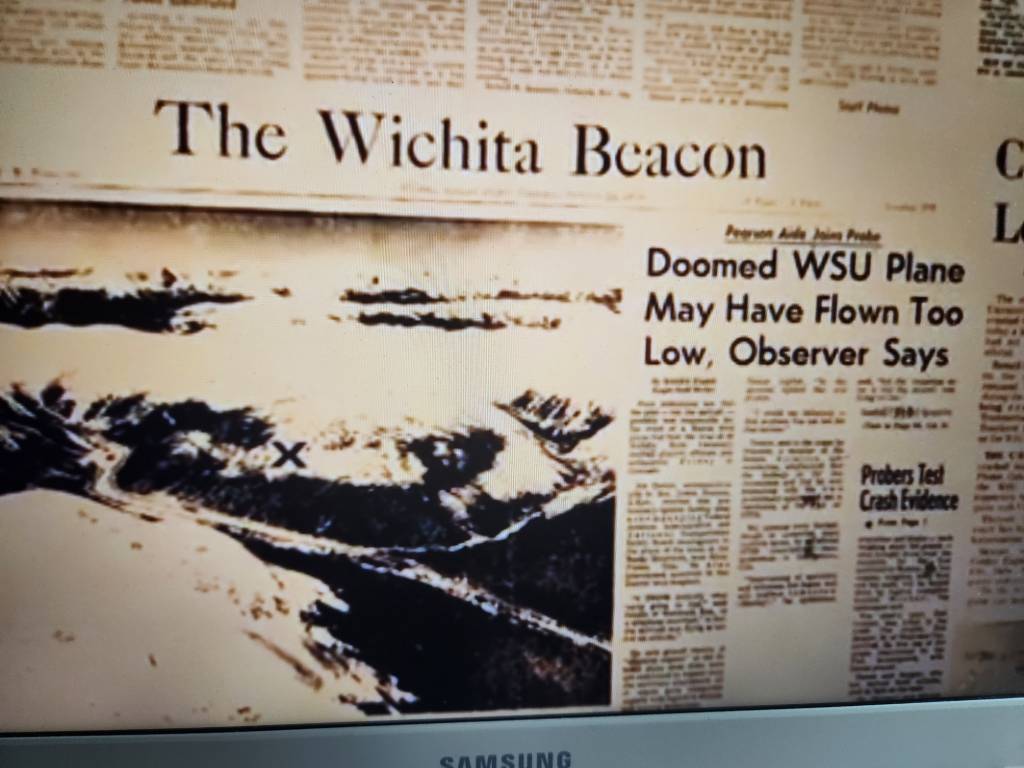

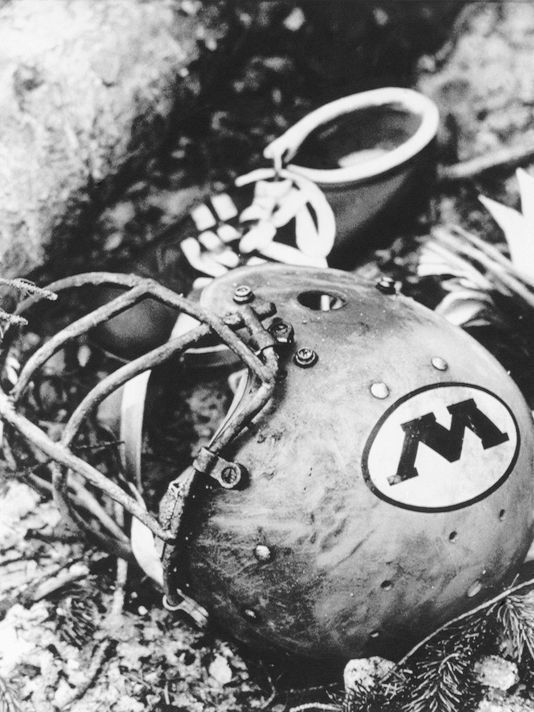

Soon it became clear that they were in a box canyon with no way to escape. Skipper banked sharply to the right. The previously docile Crocker had had enough of Skipper’s idiotic actions and then took control, banking to the left. But it must have been clear to all on board that catastrophe was at hand. You can imagine the pandemonium in the cabin as the plane vibrated, the engines stalled, and altitude was lost. Traveling at the moderate speed of 110 miles per hour, “Gold” grazed the tops of some trees and then crashed at 1:14 p.m. The fuselage broke into three parts, and a fire erupted, followed by an explosion. When the first rescue people arrived, they found a gruesome scene and an odd one, in that football helmets, cleats and uniforms were spread all over the place.

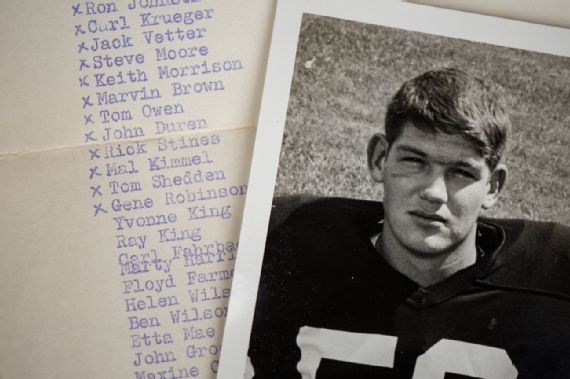

It seems right and proper to list the 31 people who died so unnecessarily that day in the Rockies: sophomore running back Marvin Brown, junior defensive back Don Christian, sophomore tight end John Duren, senior defensive back Ron Johnson, junior defensive back Randy Kiesau, senior offensive lineman Mal Kimmel, sophomore defensive lineman Carl Krueger, senior linebacker Steve Moore, junior running back/punter Tom Owen, junior tight end Gene Robinson, junior offensive lineman Tom Shedden, sophomore offensive lineman Richard Stines, senior defensive back John Taylor, senior defensive lineman Jack Vetter, Katzenmeyer, his wife Marian, Wilson, his wife Helen, trainer Tom Reeves, equipment manager Marty Harrison, dean of admissions Carl Fahrbach, ticket manager Floyd Farmer, Shocker Club chairman Ray Coleman, his wife Maxine, John and Etta Mae Grooms (husband-and-wife pair who won a trip to the Utah State game for getting the most new members in the Shocker Club), Kansas State Representative Ray King, his wife Yvonne, Crocker and stewardesses Judy Lane and Judy Dunn. It was an inconceivable loss for the city, the school and the team.

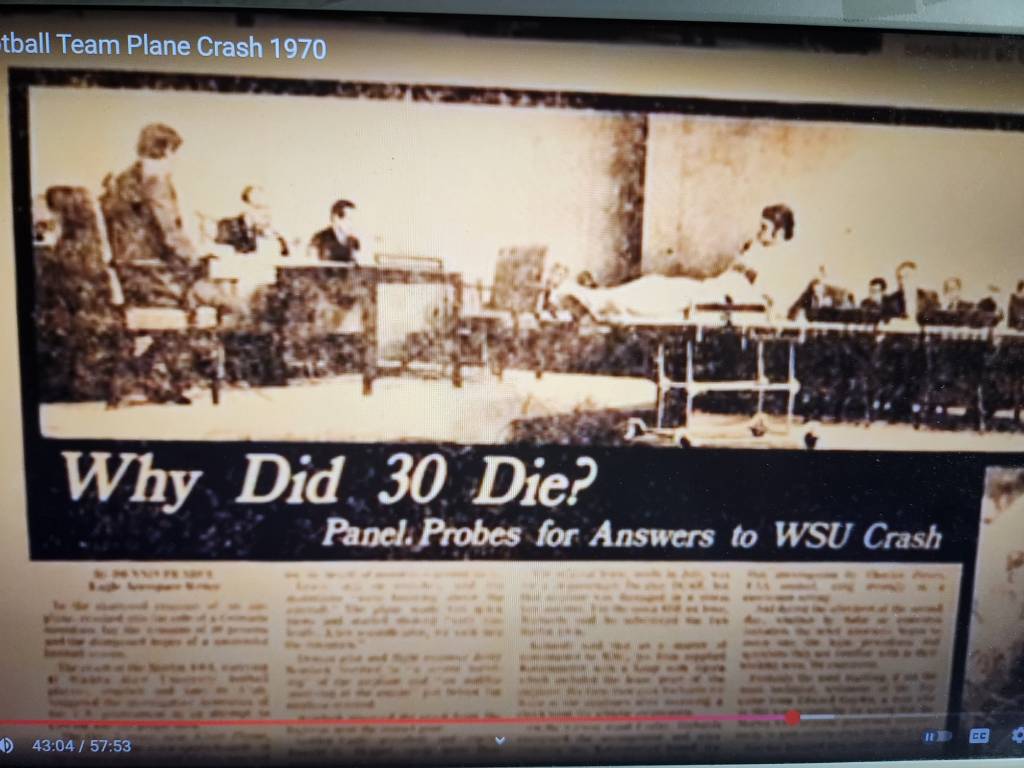

All of the other nine passengers were, of course, injured—some quite badly. Skipper, who lived until 2003, was among them. The National Transportation Safety Board did a thorough investigation, concluding that the disaster could not be attributed to weather or mechanical malfunction. The NTSB’s finger was pointed directly at Skipper: “The aircraft was intentionally operated over a mountain valley route at an altitude from which the aircraft could neither climb over the obstructing terrain ahead, nor execute a successful course reversal. Significant factors were the overloaded condition of the aircraft, the virtual absence of flight planning for the chosen route of flight from Denver to Logan, a lack of understanding on the part of the crew of the performance capabilities and limitations of the aircraft, and the lack of operational management to monitor and appropriately control the actions of the flight crew.”

Skipper acknowledged being at the controls of “Gold” from takeoff until just before it struck Mount Trelease, and he conceded that he had made the decision to take the scenic route without consulting the 27-year-old Crocker, clearly the junior partner in the cockpit. Nevertheless, he refused to accept responsibility. Indeed, he did all he could to blame the deceased Crocker. Seeking to refute most of the NTSB’s conclusions, he insisted that the right engine had caught fire and failed. Otherwise, he contended, their up-close alpine excursion would have been just a pleasant memory for the passengers, to go along with the football game in Logan. In a 1990 interview with the Wichita Eagle, he was stubborn and remorseless: “I feel I did everything that I could have done in the situation. I feel badly that it happened, of course. I feel badly that we were even flying the team that day. But I don’t feel badly about anything I did.” His Golden Eagle Aviation was shut down by the Federal Aviation Administration, and he briefly lost his pilot’s license. However, despite years of legal battles among the university, Golden Eagle Aviation and Jack Richards Aircraft Company, Skipper was never charged with a crime, much less convicted. No pariah, he went on to 16 more years of flying cargo and passengers for TransAmerica Airlines.

The Wichita State-Utah State football game, naturally, was cancelled—as was one with Southern Illinois scheduled for the following Saturday. The surviving players voted almost unanimously to carry on, calling it the “second season.” Guys who had previously been substitutes and freshmen (with special permission from the NCAA) comprised the roster; assistant coach Bob Seaman took over for Wilson. In losses to Arkansas, Cincinnati, Tulsa, Memphis State, North Texas State and Louisville, they battled valiantly and gained their foes’ respect.

In the 1986 Wichita State season—a desultory 3-8—the final game at Veterans Field was a 17-10 loss to Illinois State before just 4,233 fans. Three weeks later, the university’s Board of Trustees made the painful decision to end 90 years of Shockers football, citing financial issues (the athletic department had a $2.5 million debt that was getting bigger every year) and lack of success on the field. The WSU program, not a strong one even in the best of times, had been crippled by the 1970 plane crash.

2 Comments

Another fascinating sport history story. I enjoy your content from your thorough research but more importantly you are a great story teller. As I read and questions come up you next sentence proves the answers. Very well told my friend! And a great memorial to those young athletes.

I was present at the 1970 game against Wichita State. That crash was shocking. It was like meeting a new friend that suffered a violent death two weeks later.

I never learned the reason.

Add Comment