I remember George Arellano fondly. He was my favorite family member although our connection was remote: the father-in-law of one of my brothers. Imperturbable, friendly, well-educated, articulate and a world traveler, he was possibly the best conversationalist I have ever known. George, who died a few years ago, was a native of Santiago, Chile. I wish I would have asked his opinion of Augusto Pinochet, the Chilean dictator/president from 1973 to 1990. More to the point, what did he think of Operation Condor, the notorious nine-year campaign Pinochet instituted to combat a growing and palpable threat from far-left and revolutionary groups in countries making up the “southern cone” of South America?

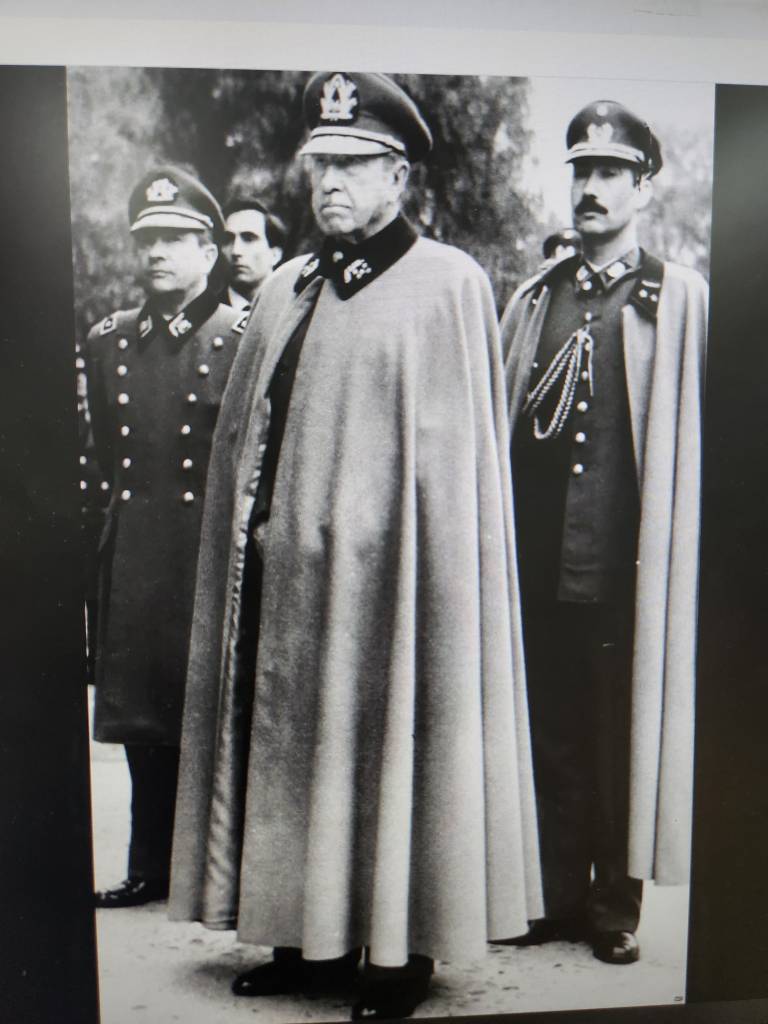

Pinochet’s choice of the Andean condor as the symbol of this effort was no accident. The largest bird of prey in the world, it has a maximum wingspan of nearly 11 feet, weighs up to 33 pounds and can soar as high as 15,000 feet and fly 200 miles in a single day. Found in the Andes Mountains and all along the Pacific coast of South America, it is a vulture—that is, it feasts on carrion, or dead animals; this avian creature has an iron stomach. While the condor is majestic and even sacred in Incan culture (Machu Picchu was dedicated to the condor), it is regarded by some people with revulsion as an ugly bird hovering between life and death.

Operation Condor, which took place amid the tensions of the Cold War, had the tacit approval and support of the United States. As early as 1968, American military officials had been urging their South American counterparts to work together. According to a recently declassified CIA document, “in early 1974, security officials from Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Bolivia met in Buenos Aires to prepare coordinated actions against subversive targets.”

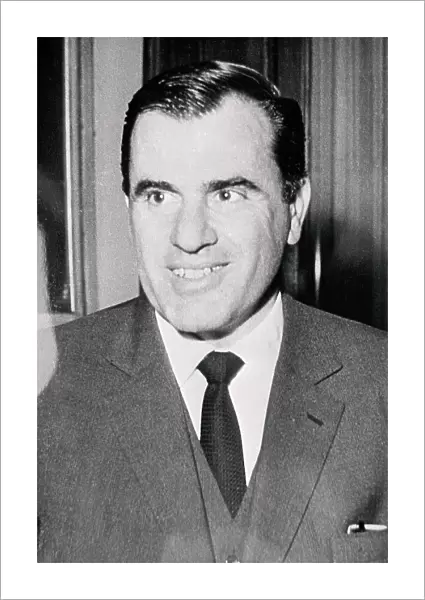

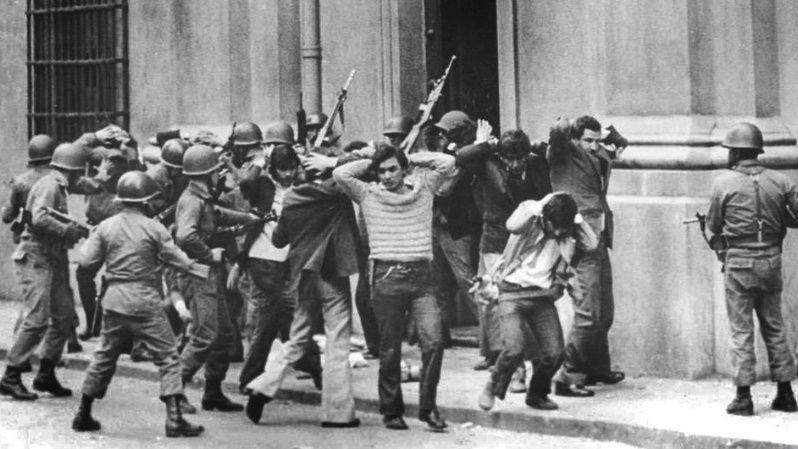

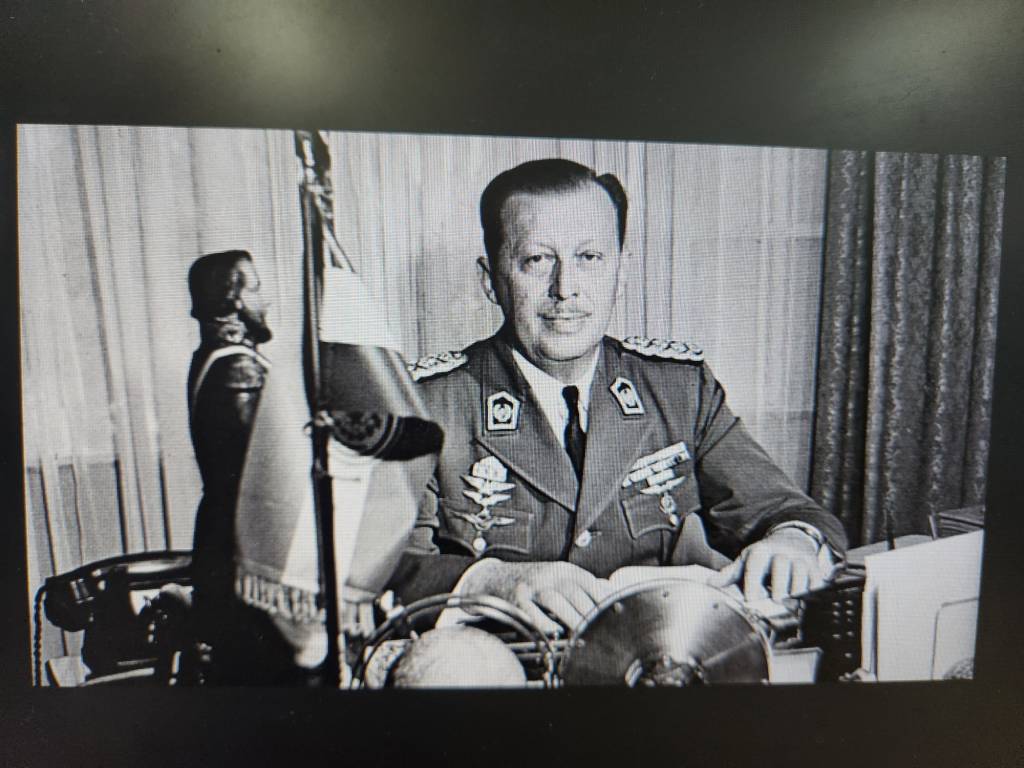

Having risen through the Chilean military ranks, Pinochet became commander-in-chief in 1972. A seemingly non-political man, he played his cards close to the chest. Above him was Salvador Allende, a Marxist who had won a fair and democratic election as president two years earlier. He was intent on a thoroughgoing re-do of Chilean society, and Pinochet found that notion abominable. He led a violent, CIA-inspired coup d’etat on September 11, 1973 culminating with Allende’s suicide. (I have never understood this. If you must die, why not go down fighting?)

Pinochet’s seizure of power was by no means unusual in that part of the world. To wit: Alfredo Stroessner—who might be fairly called the granddaddy of modern South American dictators—took control of Paraguay in 1954 and kept it for 35 long years; Joao Goulart was overthrown in 1964, commencing Brazil’s 22-year military rule; Hugo Banzer seized power in Bolivia in 1971 (his predecessor, Juan José Torres, was murdered in Buenos Aires five years later); an authoritarian military junta led by Juan Maria Bordaberry ran Uruguay (which at one point had the world’s highest ratio of prisoners to population) from 1973 to 1985; Juan Velasco Alvarado ousted Fernando Belaúnde-Terry as Peru’s leader in 1968 and was himself shown the door by Francisco Morales Bermúdez in 1975; Guillermo Antonio Rodríguez, who had deposed José Maria Velasco in 1972 in Ecuador, got the boot himself four years later; and in 1976, Jorge Rafael Videla and his fellow generals told Isabel Peron to hit the road in Argentina.

But since Pinochet thought the existing informal and bilateral cooperation among armed and security forces was insufficient to meet the threat, he directed his spy chief, Manuel Contreras, to invite about 50 men from Chile, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, Brazil and Bolivia to a conference at Bernardo O’Higgins Military Academy between November 25 and December 1, 1975. What emerged from those talks was an agreement to not just defeat but crush leftist elements. “Enemy” was broadly defined by those who met in Santiago almost 50 years ago—revolutionaries, anarchists, socialists, communists, union leaders, intellectuals, teachers, priests and nuns, artists, journalists, students and sympathizers. They would zealously go after the bad boys in their own countries, in each other’s countries and abroad.

Mostly, though, Operation Condor targeted radicals. These people, many inspired by Ernesto “Che” Guevara—sent into eternal rest by Bolivian commandos in 1967—were convinced that mere reform would not alleviate the longstanding injustice and inequity in so-called Latin America. Only violent revolt could bring on the economic and social metamorphosis they had in mind. Among these groups were the Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo, the Junta Coordinadora Revolucionaria, the Ejército de Liberación Nacional, the Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria, the Partida para Victoria del Pueblo, the Sendero Luminoso or Shining Path (“Marxism-Leninism will open the shining path to revolution”), the Montoneros and the Tupamaros. All were ruthless and willing—indeed eager—to shed blood. This is not to justify the horrors of Operation Condor, only to put them into some context.

A word now about the Americans, who wanted no more Cubas in their backyard. One can hardly overstate the importance of the economic, military and political influence of the big neighbor to the north, for whom the sainted Che had such contempt. Presidents Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, ambassadors, CIA station chiefs in Santiago, La Paz, Buenos Aires, Asunción, Montevideo, Lima, Brasilia and elsewhere and national security advisor/secretary of state Henry Kissinger constantly gave mixed signals. So it should come as no surprise that when Pinochet et al. got both the green light and the red light, they took green as the bottom-line answer. Kissinger, by the way, was a snob who considered South America culturally irrelevant and economically insignificant.

Operation Condor went into force immediately, and this was oppression on an industrial scale. Abduction, torture, extrajudicial killing, rape—virtually nothing was prohibited in the effort to triumph over perceived foes of the eight governments (Peru and Ecuador joined later) involved. If ever the U.S. realized that things had gone too far, it came on September 21, 1976, when a massive car bomb killed Orlando Letelier in Washington, DC. An economist, politician and diplomat during Allende’s presidency, Letelier had been driven into exile and was working for a left-wing think tank. He was the leading voice of the Chilean resistance and thus an irritant to Pinochet. (A book on this topic, Assassination on Embassy Row, was written by John Dinges in 1980.) “Hits” were also made in Paris, Rome and Lisbon.

Due to the clandestine nature of Operation Condor, many facts remain unclear. Still, the truth about that dark time in South America—generally regarded as having ended with the fall of Argentina’s military dictatorship on October 30, 1983—has dribbled out. Note the roundness of these numbers: 400,000 people were arrested and/or imprisoned, between 400 and 500 cross-border killings occurred, and 60,000 suspected leftists died as a result of shootings, torture, car bombs like the one that killed Letelier and even being dropped from airplanes into the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. I draw it to your attention that the torture employed during Operation Condor was particularly brutal. Some U.S. military and intelligence men who had fought in World War II said it was much worse than the Germans’ and Japanese’ handiwork, even comparing it to the Spanish Inquisition.

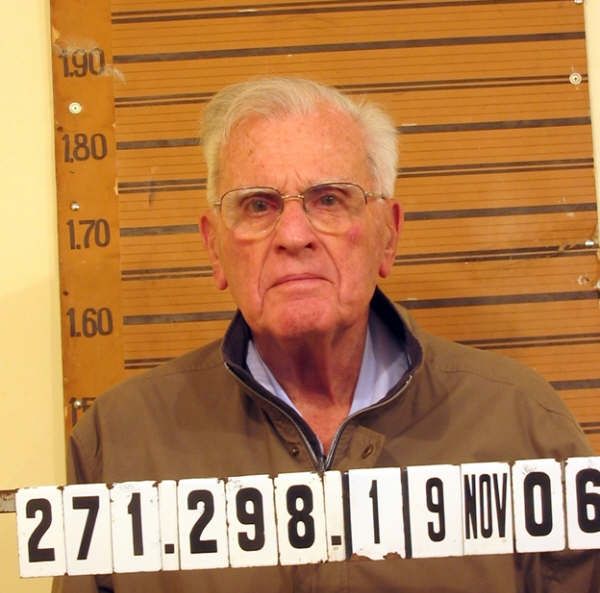

As for Pinochet himself, he served as leader of Chile’s military junta from 1973 to 1981 and as de jure president for another decade. He passed laws intended to give himself immunity, but things had changed. The noose had been tightening for awhile, with an increasing number of Operation Condor agents—including his main assistant, Contreras—convicted and serving time. He was put under house arrest during a medical stay in London in 1998. Released on grounds of ill health 18 months later, Pinochet returned to Chile and was again placed under house arrest. This man, who used to wear a gray cape that some people thought made him look especially sinister—rather like an Andean condor—died on December 10, 2006 with around 300 criminal charges (human rights violations, tax evasion and embezzlement among them) pending. Nevertheless, more than 50,000 mourners attended his funeral in Santiago. He still casts a long shadow in Chile.

11 Comments

Very interesting, Richard. I would be interested in how you make choices regarding your subject matter. Many of the varied subjects that you write about are not in my wheelhouse of curiosity. Of course, I work for an attorney and have been a paralegal for over 40 years now and I have made a formal declaratory statement of my notice to “retire at the end of the year” for the last ten years … guess I love the guy. Thanks again for sharing.

Bettye: Other than a visit to Peru and Bolivia 29 years ago, I have no direct connection to that part of the world. But why should I not care? I would ask you–why is this not in your “wheelhouse of curiosity”?? I care about people from all parts of the world, not just in my immediate circle, my life, my culture. Maybe I should care only about White people from Texas…

I remember some of this when I was in high school and college. It was hard to tell the good guys from the bad guys. This is part of where the term banana republic became popular. They are still not super stable.

So true…who was good and who was bad? Pinochet and his buds still have many defenders.

Great synopsis of the various dictators of South America. We worry about the instability of the Middle East yet South American instability is in our own backyard.i am a dreamer….can’t we just agree to disagree and coexist peacefully. What makes humans need to be in control?

Thank you, Janet. You know human nature…

Very interesting event of social economic political event spearheaded by these power hungry megalomaniac assasins coming

from South America.

The junior of Hitler!

Good point, Lelen.

Very interesting. Your incredible research makes your perspective most credible. If only this standard of literary arts were more widely available. I was unaware of these events or persons even while they occurred. Thank you for the enlightenment.

On a personal note I drove past your Alma mater UT-Austin yesterday. I was at TAMU while you were at UT. Best to you in the new year.

Thanks so very much, Jeff. I first got into the writing/editing biz in 1982–43 years ago. To research and write an article like this is very satisfying.

I liked it. It is incomprehensible to most of us.

It was lightly covered by the US press. Too many moving parts. No way to get a handle on who was doing what and why. Besides, Pogo was much better reading.

I went to school, Truett through Texas A&M, with a gentleman with a long military career ahead of him.

He was in the middle, covertly, of much of your discussion. I know bits and pieces from him, but he is silent otherwise.

I do not know how to frame questions to him. We went 35+ years with little contact. This will help me do just that. Assuming he is willing to answer any of them.

Add Comment