I wish I could remember what prompted me, in the summer of 1976, to drive my Ford station wagon to downtown Austin and find the intersection of Sixth and Brazos, the site of an old furniture store. It had, for the past year, been the home of a blues club named Antone’s. While I do not pretend to have been a serious music aficionado, I was aware of and savored mid-70s Austin’s pulsating energy and vibe. My home—one room in a subdivided old house on West 29th Street for which I paid $75 per month in rent—was covered from floor to ceiling with the posters of musical engagements at places such as Antone’s, Armadillo World Headquarters, Soap Creek Saloon, Rome Inn, the Skyline Club, the Continental Club, the Broken Spoke and Cactus Cafe.

Finally, I was going to give Antone’s a try. I paid a five-buck entry fee, nursed a beer and watched James Cotton and his band belt out one tune after another. The power and rhythm of this music gripped and entranced me. Cotton, a native of Tunica, Mississippi (which, coincidentally, I would visit seven years later during a tour of the Magnolia State) played the harmonica and sang. I cannot be certain, but he and his bandmates probably reprised “Don’t Start Me Talkin’,” “Dealing with the Devil,” “Turn On Your Love Light,” “Sweet Sixteen” and “She’s Murder”—also known as “Murder in the First Degree.” I walked out of Antone’s that night dazzled.

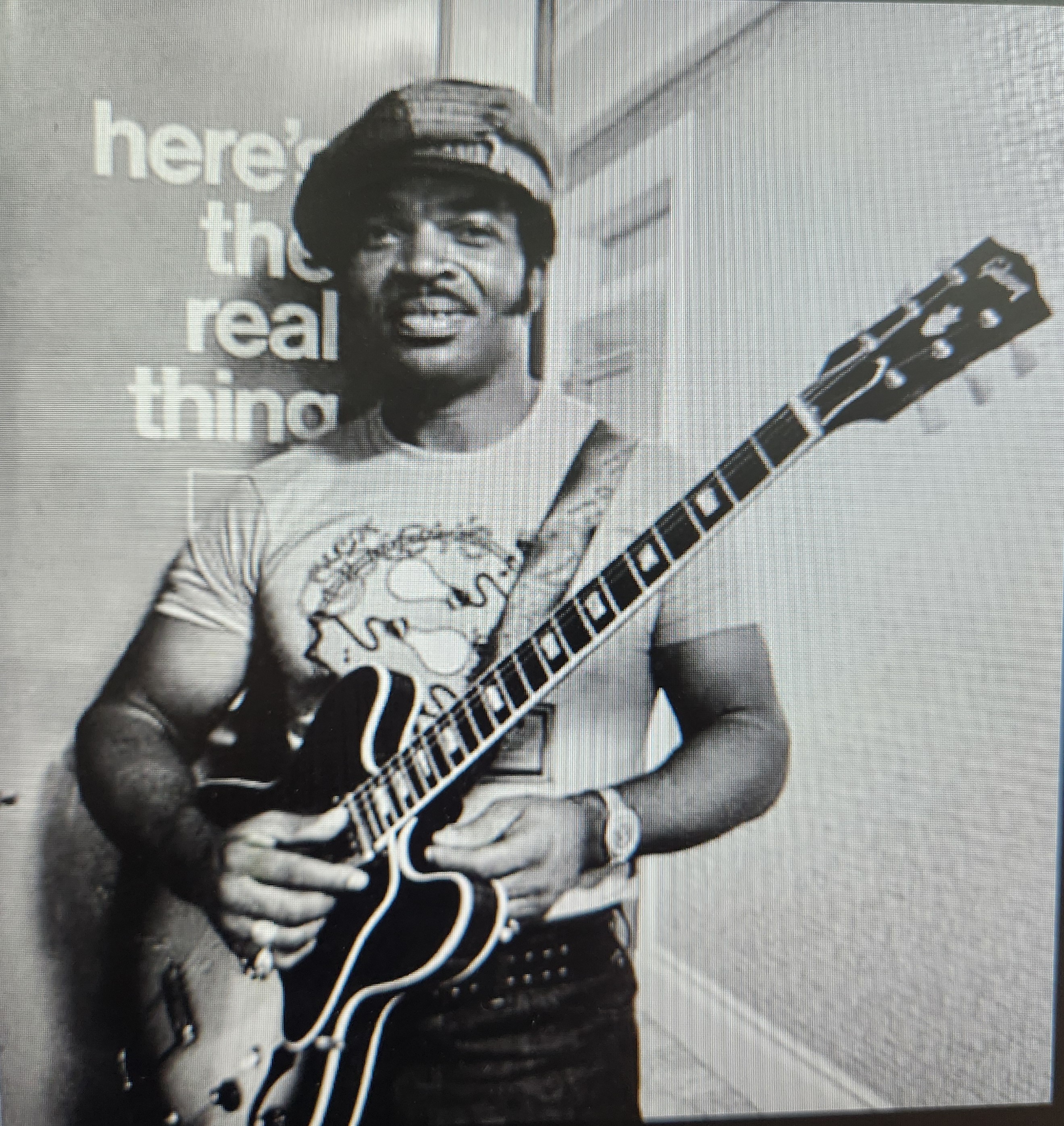

Even so, I don’t think I went back there before leaving Austin for Dallas in late ’76. Five years later, however, I had returned. By that time, the club had moved out to a spot on Burnet Road and then found a new home at a former Shakey’s Pizza parlor near the University of Texas campus. This is where I was a somewhat steadier patron of Antone’s. But I can recall the names of just two bandleaders I saw there—Koko Taylor and Matt “Guitar” Murphy. Murphy, as you may know, had a cameo role in the Blues Brothers movie; the scene where he argued as Aretha Franklin sang and danced to “Think” is one I have seen again and again on You Tube. During intermission of his show, I had the chance to briefly meet the muscular Murphy.

I used to listen to Larry Monroe’s “Blue Monday” show on KUT-FM which he hosted for nearly 30 years. (It is hardly germane to this story, but I wrote a feature article on Monroe that appeared in the Daily Texan circa 1982.) Monroe would not just play the records of blues musicians, he would give brief summaries of their lives and musical backgrounds. For example, before playing a song by Edward James “Son” House, he would inform listeners that House was a native of the Delta hamlet of Lyon, Mississippi; that he vacillated between preaching the Gospel and playing raucous secular music; that he spent time at the notorious Parchman Prison after shooting and killing a man in a house party; that he served as inspiration for Robert Johnson’s “Preaching Blues” and “Walking Blues”; that he had given up music and moved to Rochester, New York when Alan Wilson of Canned Heat found him and gave him the recognition he merited; or that he played for mostly White audiences in coffeehouses, folk festivals and venues like Antone’s before his death in 1988. Such information enriched the experience for Monroe’s listeners.

Monroe, relentlessly plugging Antone’s, would do the same for Muddy Waters, Albert King, Bobby “Blue” Bland, Little Milton, John Lee Hooker, Sunnyland Slim, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Mance Lipscomb, Clifton Chenier, Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, Luther Tucker, Hubert Sumlin, Otis Spann, Willie Dixon, Jimmy Reed, Buddy Guy, Albert Collins, James Brown, Ray Charles, B.B. King et al. The latter three gentlemen eventually priced themselves out of such a relatively small market; Antone’s had a limit of 600 patrons. No offense was meant or taken, as most of them had paid their dues by playing at juke joints, pool halls, roadhouses and honky-tonks throughout the South during the Jim Crow era.

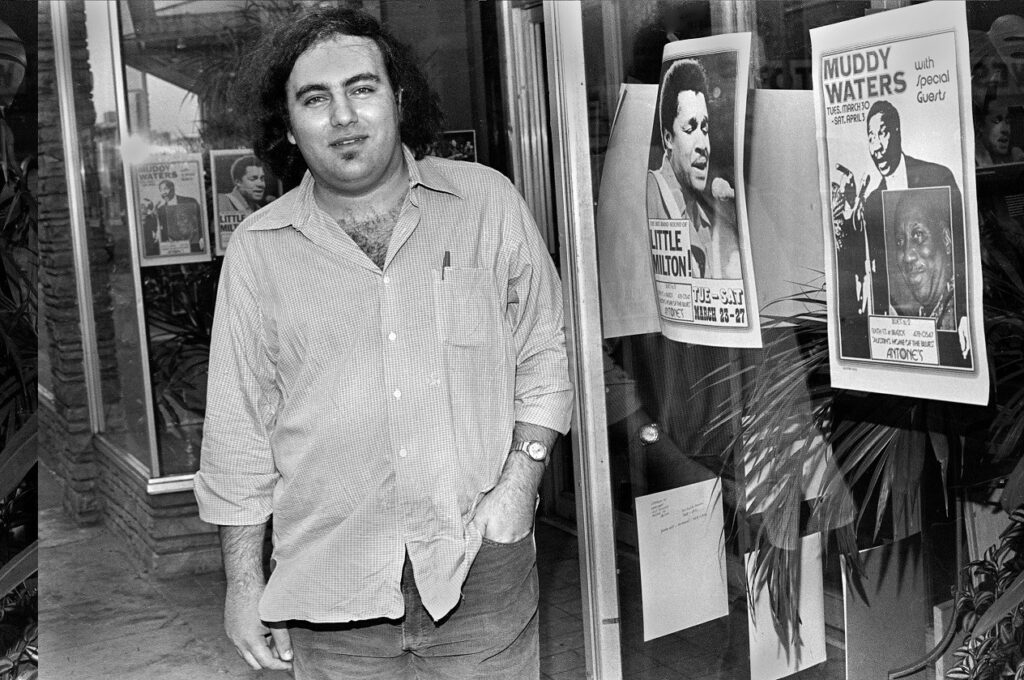

The club’s founder was Clifford Antone, a man of Lebanese descent who had grown up in Port Arthur and come to Austin in 1965 to attend UT. He never graduated. Antone, previously a fan of Led Zeppelin, Eric Clapton and Fleetwood Mac, had an epiphany somewhere along the way and fell “crazy in love with blues music.”

He often served as the emcee, introducing the musicians and urging audience members to give them full appreciation. I hesitate to even speculate about some of the things that used to happen in the back rooms of Antone’s, but one involved the rather fearsome Albert King and Stevie Ray Vaughan having a spirited blues jam; the younger and paler man proved that he could handle an “axe.” They later did it onstage.

Antone cultivated something of a Godfather-like persona. He enjoyed having people believe that he had mob connections or protection, and that did nothing to hurt the club’s aura. (I will say, however, that I never felt the least bit intimidated the times I visited.) He always strove to pay musicians—headliners and sidemen alike—fairly. But to do that and stay solvent, Antone went outside of the law. Twice he was arrested, indicted, convicted and imprisoned for drug smuggling and money laundering. He was no small-time drugrunner, either, as his second conviction was for bringing in more than 10,000 pounds of the devil weed. Had current watered-down marijuana laws been in effect in Antone’s heyday, he might never have been incarcerated. Still, the correctional facilities in Big Spring (1984–1986) and Bastrop (2000–2003), where he did time, can hardly be compared to Huntsville. Getting tossed into the general population there can scare a man enough to make him toe the line for the rest of his days.

Antone’s mother and sisters, local singer Angela Strehli and some Port Arthur friends ran the place while he was gone. The club, which was more famous than ever (Bob Dylan, members of U2 and others were known to visit after giving big shows at the Erwin Center), was harder to run without all that funny money. It closed and reopened a couple of times, but he was the same generous man he had always been. He taught courses in blues history at UT and Texas State in San Marcos, organized a concert to benefit victims of Hurricane Katrina and served as Pinetop Perkins’ legal guardian, although it was Antone who died first. In those final few years, Antone—who had icy relations with Armadillo World Headquarters founder Eddie Wilson and Broken Spoke founder James White—was friendly with them, and they swapped jokes and stories rather than barbs.

After dying of a heart attack at age 56 in 2006, Antone has been the subject of numerous admiring documentaries and books. A plaque honoring him stands at Sixth and Brazos, site of the original venue. When it came to the blues in Austin, Clifford Antone called the tune.

James Cotton…

Matt “Guitar” Murphy…

Antone…

Feigning fisticuffs with Muddy Waters…

Add Comment