I have written elsewhere about smug, I’m-somebody-and-you’re-nobody jocks like Archie Manning, Eric Metcalf, Earl Campbell, Spencer Haywood and Alberto Salazar. I had the occasion to meet each of these men, and soon came to rue the day I did. But not every athlete I have encountered, active or retired, is like that. I can think of no better example than Raymond Berry.

The circumstances of our meeting were unique. It was in the spring of 1989, the first season of SMU’s return from the NCAA-administered “death penalty” for allowing boosters to run amuck and give football players cash and cars on the side. The athletic department must have been trying every possible way to generate enthusiasm for getting back to the gridiron. This was a somewhat serious game at Ownby Stadium between what would be the 1989 team and a group of ex-Mustangs. One of the “old guys” was my friend Jerry LeVias, and thanks to him I was allowed to roam the sidelines. The coach of the youngsters was Forrest Gregg, a one-time star lineman at SMU and then with the Green Bay Packers. I did get the chance to meet Gregg, who already had head coaching experience with the Cleveland Browns, Cincinnati Bengals and the Pack. Gregg was mountainous (6′ 4″ and 250 pounds or so) and quite pleasant, but he did not make nearly the impression as Berry, who was coaching Levi and the others.

In retrospect, it’s surprising that Berry was in Dallas that day since he was about to start his final season as coach of the New England Patriots. We talked for five minutes after the game, the results of which are long forgotten. I could not help noticing Berry’s demeanor and attitude toward me. To say he had no ego would be wrong because the man was fully aware of who he was and what he had achieved in the sport. But he simply refused to big-time me. He listened to me—whatever the heck I was saying—closely and looked me straight in the eye. His attention was 100% focused on me. I became a genuine Raymond Berry fan that day.

He was born in Corpus Christi in 1933 but grew up in the east Texas town of Paris. His father, Ray, was the head football coach at Paris High School. He yearned to play for his father but was no great physical specimen—not big or especially strong, not fast (4.8 seconds in the 40), and his eyesight was poor. Contact lenses fixed the latter issue, and meticulous preparation, good practice habits and deep-seated confidence mitigated the effect of the first three. Berry was a starter only in his senior year. Although the team went undefeated, he drew no interest from major college recruiters.

He spent a season at a junior college, Schreiner Institute, before transferring to SMU. The coach, Rusty Russell, gave him a shot only as a favor to his father. Berry practiced like a man possessed, earned a scholarship and was a member of the team from 1952 to 1954. He caught just 33 passes because Russell and his successor, Woody Woodard, were run-first coaches.

Nevertheless, some Baltimore Colts scout must have seen something in the determined Mustang because he was taken in the 20th round of the 1954 NFL draft as a “futures pick.” Berry played his senior season on the Hilltop, serving as captain and earning all-SWC honors. (No offense to Ron Beagle of Navy and Max Boydston of Oklahoma—that year’s consensus all-America wide receivers—but they are long forgotten; Berry is not.)

A long-shot to make the Colts, he threw himself into preparation, studying film and opposing players, and coming up with unorthodox training methods. He started seven games as a rookie, but things really changed in 1956 when a free-agent QB named Johnny Unitas showed up.

I will not insult your intelligence by reciting just what a dramatic effect Unitas-to-Berry had on pro football. You already know that they were very much alike in their dedication to the game. In 1957, Berry led the NFL in receiving yards, and the Colts won the championship in 1958 (12 catches and one TD in the “greatest game ever played” sudden-death overtime defeat of the New York Giants) and 1959. Berry, who almost never dropped a pass he could get his hands on and fumbled only twice, played through 1967. When he retired, he had 631 receptions and 68 touchdowns. He reached Canton in 1973.

Berry had not planned to do any coaching, but he got a call in 1968 from Tom Landry to help with the Dallas Cowboys’ receivers. He spent two years at the University of Arkansas before returning to the pros—the Detroit Lions, the Cleveland Browns (under Gregg) and the New England Patriots. Up in Boston, he became the head coach in 1984. His 1985 team, led by another Mustang, running back Craig James, got hot and won three playoff games on the road, only to face the mighty Chicago Bears in Super Bowl 20. Berry took the blame for the 46-10 rout: “We couldn’t protect the quarterback, and that was my fault. I couldn’t come up with a system to handle the Bears’ pass rush.”

Soon after that game, the franchise was in an uproar over accusations of rampant drug abuse. Berry, a straight-arrow coach (he had been gently derided by his SMU teammates in the mid-1950s as “Jack Armstrong, the all-American boy”), cut his players no slack regardless of whether they smoked an occasional doobie or did harder stuff to the point of hurting their performance on the field. After the 1989 season, owner Victor Kiam forced his resignation. He spent one season as an assistant in Detroit and one in Denver, and then retired.

Berry, who always took good care of himself, is now 90. He lives with his wife Sally in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. Whether he is “the finest man to have walked the earth since Jesus Christ,” as one Baltimore sportswriter put it, I do not know. But he certainly impressed me that day at Ownby Stadium.

Berry at SMU…

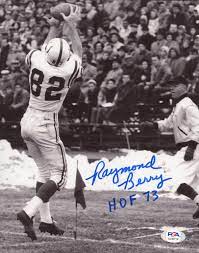

Berry catches a pass in some snowy NFL game…

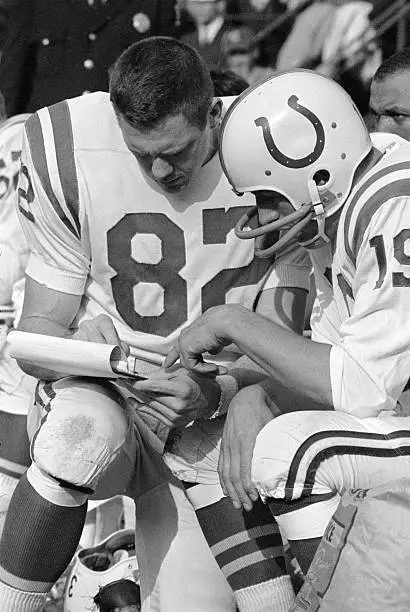

Berry and Unitas, two students of the game…

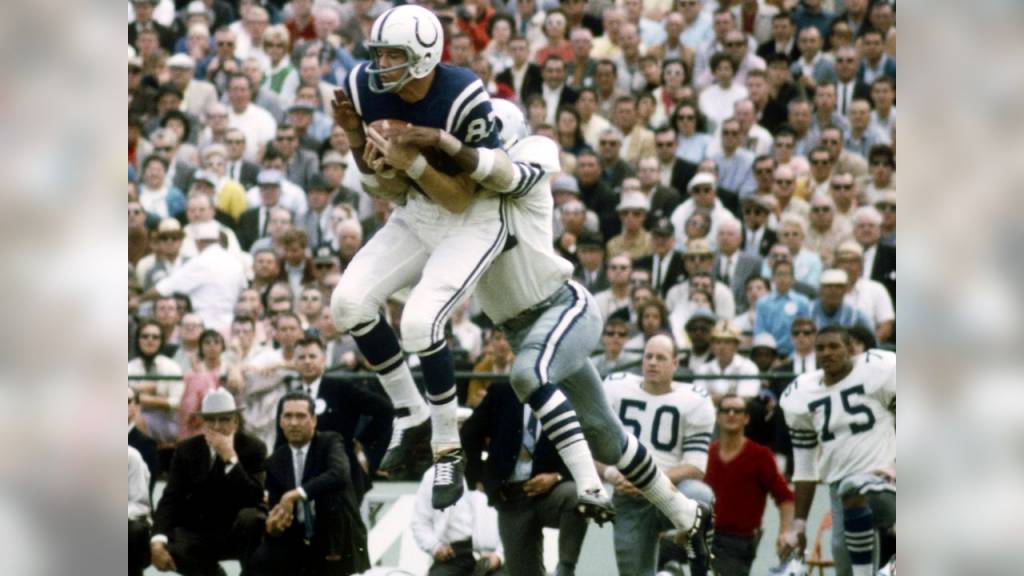

Berry operates against the Dallas Cowboys in the Cotton Bowl (where he had played as a collegian)…

Tom Brady and Berry at New England’s training camp, 2017…

4 Comments

Great read! I remember the Colts in the Unitas days, great team.

Me too…the Unitas-to-Berry connection!!

I went through First Ward Grade School with him and can tell you Raymond was a down to earth guy even as a youngster. The last time I saw him in 1990 at Paris High School reunion, he was the same low key down to earth guu. A real gentleman like his Dad who was also in attendance.

When I was a senior at Manhasset High School, our quarterback (Patty McCrarry) pretended to be Johnny Unitas and I was Raymond Berry. Patty had been a ball boy at the Baltimore Colts summer camp. Patty would throw inaccurate passes to me in practice claiming Ray Berry could catch anything. Although I had a fairly successful highschool career as an offensive end, Rutgers University made me a defensive end in 1964. However, Raymond Berry continued to be my idol.

Add Comment