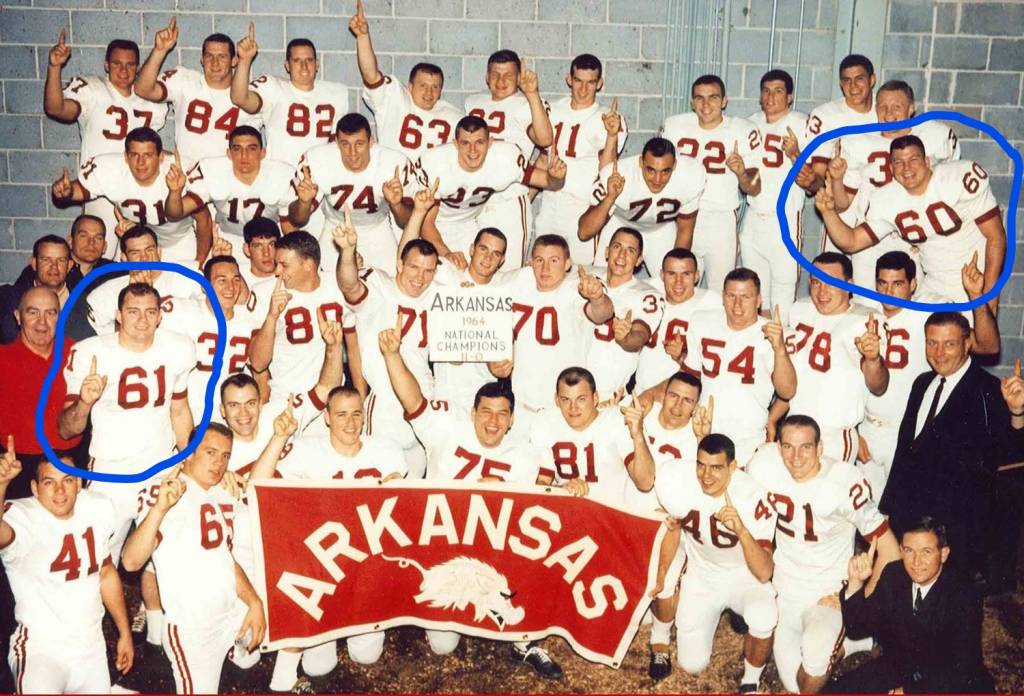

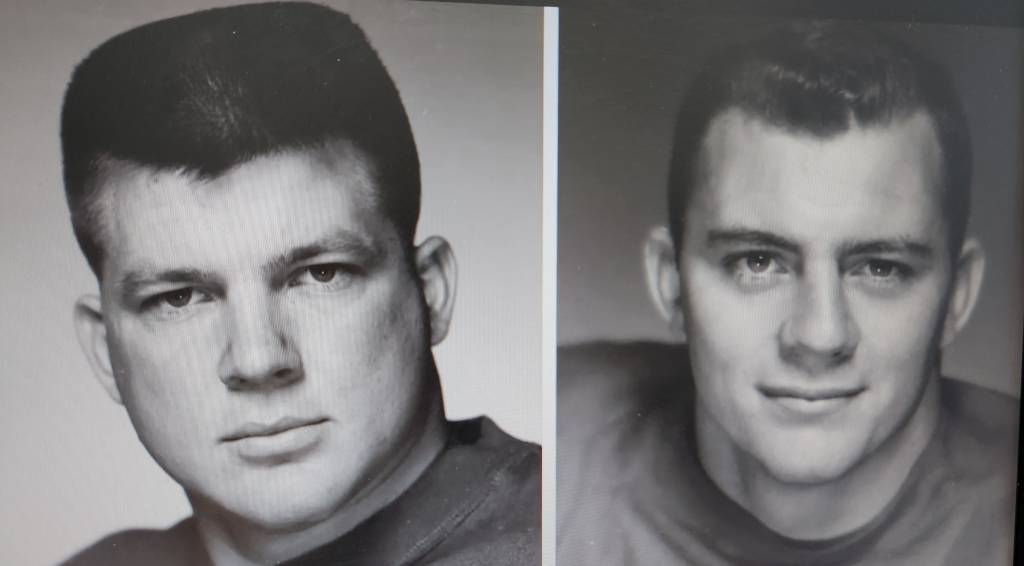

They met in September 1961 as freshman recruits on the University of Arkansas football team. Both were linemen—Jerry Jones of Little Rock on the offense and Jimmy Johnson of Port Arthur, Texas on the defense. Assigned by coach Frank Broyles as roommates on the road, they were not all that close and surely had no idea of the strange kismet that would bind them together in future years. In 1964, the Razorbacks went undefeated in the regular season, beat Nebraska in the Cotton Bowl and were crowned national champions; Johnson made all-Southwest Conference.

Jones’ father, Pat, owned a large insurance company. After graduation, he was given a high-level job there and tried his hand at several other business ventures. Some flopped. He earned a master’s degree (also at UA) and then started wildcatting for oil and gas. In this, Jones did considerably better. Football was still in his blood, though. Other than drilling wells in Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma and Texas, he hung out in hotel lobbies when NFL and AFL owners were meeting, in hopes of making some sort of connection. Jones’ effort to buy the San Diego Chargers was unsuccessful because he could not come up with the $5.8 million asking price.

Johnson, meanwhile, was hustling his way up the football coaching ladder: an assistant at Louisiana Tech, Picayune (Mississippi) Memorial High School, Wichita State, Iowa State, Oklahoma, his alma mater and Pittsburgh, then as the head man at Oklahoma State and Miami. His strutting, swaggering, trash-talking Hurricanes won the 1987 national title.

The late 1980s were a dark time for one of pro football’s most glamorous franchises, the Dallas Cowboys. Coach Tom Landry had seemingly lost his touch, as the team went 7-9 in 1986, 7-8 in 1987 and 3-13 in 1988. Average attendance at Texas Stadium games had dropped to 49,000. Compounding matters was that owner H.R. “Bum” Bright was losing a million dollars in cash every month. He needed to sell.

Jones was interested, but Bright wanted $140 million for the team and stadium. He put up $90 million, borrowed the rest and listed everything he owned as collateral. Pat Jones told him: “Son, this is the big time. You cannot fail.”

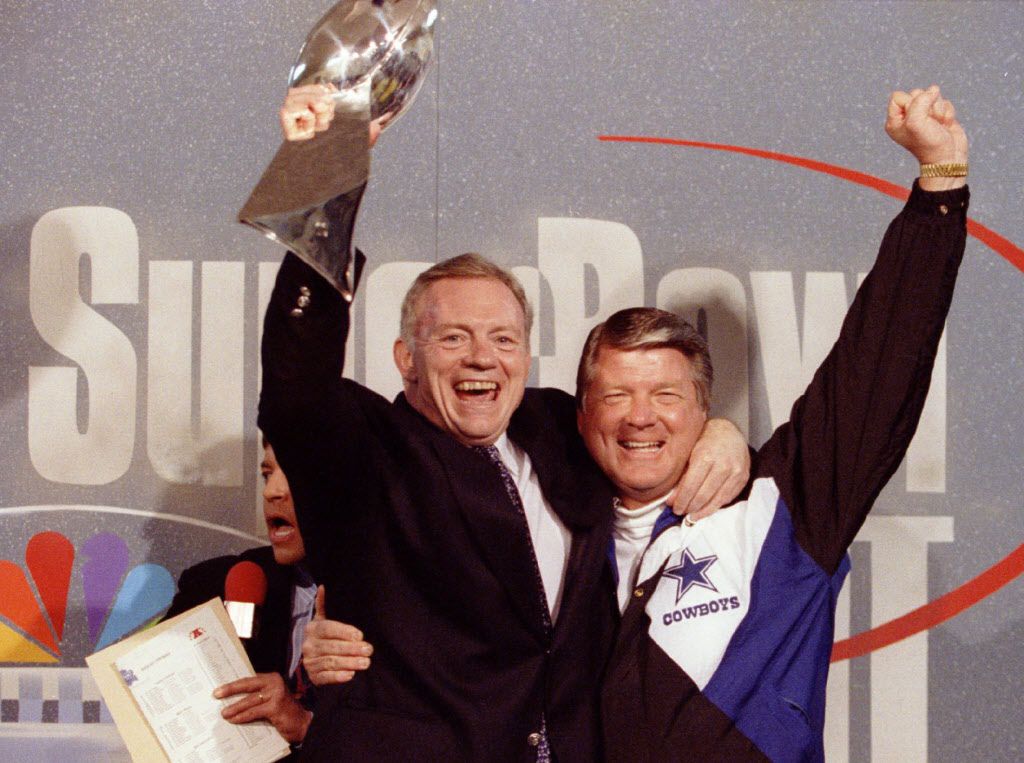

He had no intention of failing. Jones, who in his introductory press conference, vowed to be involved in everything “from jocks to socks,” took advantage of the NFL’s $30 million line of credit and started implementing changes. Creative and energetic, he found ways to make the Cowboys profitable. Most notably, he eased Landry into retirement and brought in his old Razorbacks teammate. Johnson, whose contract gave him final say in all purely football decisions, cleaned house. Dallas went a horrendous 1-15 in 1989. Jones and Johnson suffered all sorts of slings and arrows, but they held firm. Wide receiver Michael Irvin, who had been a rookie in 1988, was joined by quarterback Troy Aikman in 1989 and running back Emmitt Smith in 1990. Other heady draft choices, trades and free agent signings put the Cowboys on an upward trajectory: 7-9 in 1990, and 11-5 in 1991 and the team’s first playoff victory in a decade. I don’t need to tell you what happened in the next two years as Jones and Johnson ended up grinning like maniacs and clutching a pair of Vince Lombardi Trophies.

Let us take a few steps back in this story, back to 1989 when Jones was in negotiations with Bright about purchasing the team. He had been $50 million short, not an insubstantial sum. Fortunately for Jones, a friend with very deep pockets came to the rescue. I refer to Bandar bin Sultan al-Saud, better known as Prince Bandar. Born in Taif, Saudi Arabia in 1949, he was from the royal line on his father’s side. His mother, interestingly enough, was an Ethiopian maid—possibly a concubine. Eventually, he was made part of the royal family in that petroleum-rich nation. Bandar graduated from the United Kingdom’s air force academy and got further training as a fighter pilot in Alabama and Texas. He was at Love Field when, by happenstance, the Dallas Cowboys were returning from a game. Taken with their aura, he became a fan that night in the early 1970s. The extent to which he was involved with the team in those years, I do not claim to know. However, I assume he paid for one of the fancy suites overlooking the football field rather than sitting with what Dallas sports writer Blackie Sherrod used to call “the great unwashed.”

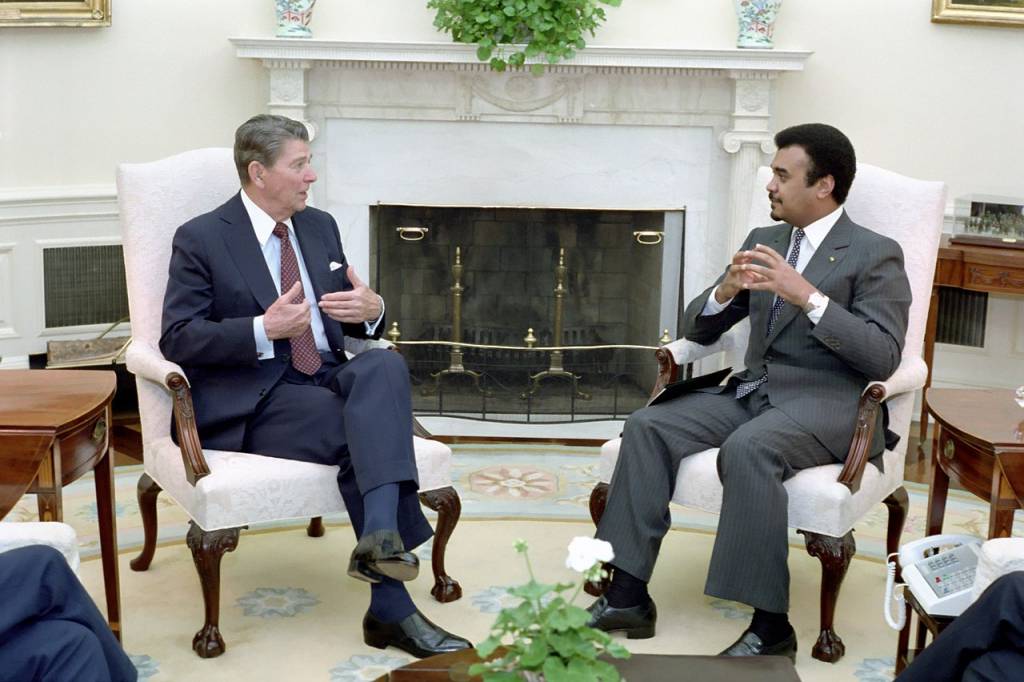

Bandar, at home in full Arab dress or in a bespoke three-piece suit, seemed to bridge the two cultures effortlessly. Affable and full of bonhomie, he was King Khalid’s personal envoy starting in 1978, lobbying Congress for the sale of military hardware to Saudi Arabia and dealing with Presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan. Bandar became the ambassador to the U.S. in 1983, holding that office for 22 years. He was in and out of the White House more often than most Cabinet members. The “peasant prince” was the toast of Washington because nobody had access to so many people in high places or came with so much money. He played a key role in keeping world oil prices stable. Brent Scowcroft, national security advisor under Presidents Gerald Ford and George H.W. Bush, called Bandar “flamboyant, dramatic, personable, smart and probably manipulative.” It was Bandar, I will add, who orchestrated the evacuation of 140 Saudis (several of them relatives of Osama bin Laden) in the days right after 9/11 when the skies over America were supposedly in lockdown. He was also behind a nationwide PR campaign in which the kingdom heartily disavowed bin Laden and his murderous crew. Nevertheless, it later came out that his wife, Haifa bint Faisal al-Saud, had circuitously sent $130,000 to two of the 9/11 hijackers.

An incident occurred at an NFL gathering in Orlando, Florida in early 1994 that brought the glory days to a sudden end. Johnson was sitting at a table with several former Cowboys coaches and administrators. Jones happened to come by and proposed a toast to two Super Bowl winners. When he got a cool reception, he cursed them and walked away. A few drinks later, he was talking to Ed Werder and Rick Gosselin of the Dallas Morning News. Jones opined—emphasizing that this was on the record—that “500 coaches could have won those two championships.” His words were duly printed, Johnson soon had a $3.9 million go-away present, and Barry Switzer (yet another old Razorback) was in as Dallas’ head coach.

Jones and Johnson never had an ideal working relationship, if only because the owner was not content with being the owner. He was his own general manager and sometimes stuck his nose into player personnel issues and even game management. Jones was convinced he knew football as well as Johnson.

At least twice, Bandar was the subject of explosions between the two. On December 27, 1992, a 27-14 victory over the Chicago Bears, Johnson turned around and noticed the prince standing on the sideline with his 20-member entourage. Johnson was irate and even more so after the game when Jones brought them into the Cowboys’ locker room. And something similar transpired on December 26, 1993, a 38-3 defeat of the Washington Redskins. This time, Johnson closed the locker room and left both Jones and Bandar outside waiting. When the doors opened and they were able to enter, Johnson breezed by them and left.

Obviously, Jones had good reason to be grateful to Bandar for having facilitated his purchase of the team in 1989 and being such a supporter—his personal jet was painted metallic blue and silver, the Cowboys’ colors. In Jones’ office, there is a black-felt display box holding a silver-and-platinum Dallas Cowboys helmet. It is inscribed, “To my friend Jerry Jones. You said you would do it, and you did it. Bandar.”

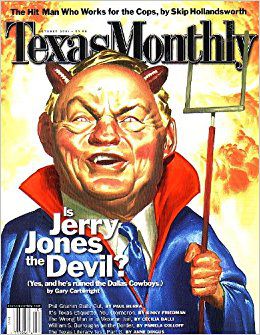

Yes, Dallas won Super Bowl 30 with Switzer at the helm. But 28 seasons have passed and they have not reached another Super Bowl, much less won one. The team has been in limbo for a long time, and coaches have come and gone—Switzer, Chan Gailey, Dave Campo, Bill Parcells, Wade Philips, Jason Garrett and now Mike McCarthy. All of them were, and are, subservient to Jones. On the other hand, Jones got a shiny, new $1.4 billion facility (AT&T Stadium) built in Arlington in 2008, more than 93,000 fans show up for home games, and the franchise is worth a staggering $8 billion. Jones has his critics, some rather ferocious, but who can argue with that?

As for Prince Bandar, he came under more press scrutiny after 9/11. It was also revealed that he had been involved in the Iran-Contra scandal and given $10 million to the CIA to perform covert operations. He was recalled as Saudi Arabia’s ambassador to the U.S. in 2005. By that time, he had moved away from the Cowboys. Bandar dealt with health problems and had some explaining to do to his political masters in Riyadh, who thought he had grown too cozy with the Americans; nor did they appreciate how he had sometimes made policy on the hoof only to inform the King later. Bandar’s life is not quite so hectic these days, but he still serves in some important positions for the Saudis.

And finally, Johnson. After a couple of seasons as an NFL television announcer, he replaced Don Shula as the Miami Dolphins’ coach. His run, from 1996 to 1999, fell short of expectations. Johnson’s last game was a humbling 62-7 playoff defeat at the hands of the Jacksonville Jaguars. He resigned the next day.

Jones (61), Johnson (60) and teammates celebrate 1964 national championship after Cotton Bowl win over Nebraska….

Johnson and Jones as collegians….

Coach and owner-GM at Texas Stadium…

Jones and Bandar celebrate after some Cowboys TD….

Texas Monthly cover, October 2001….

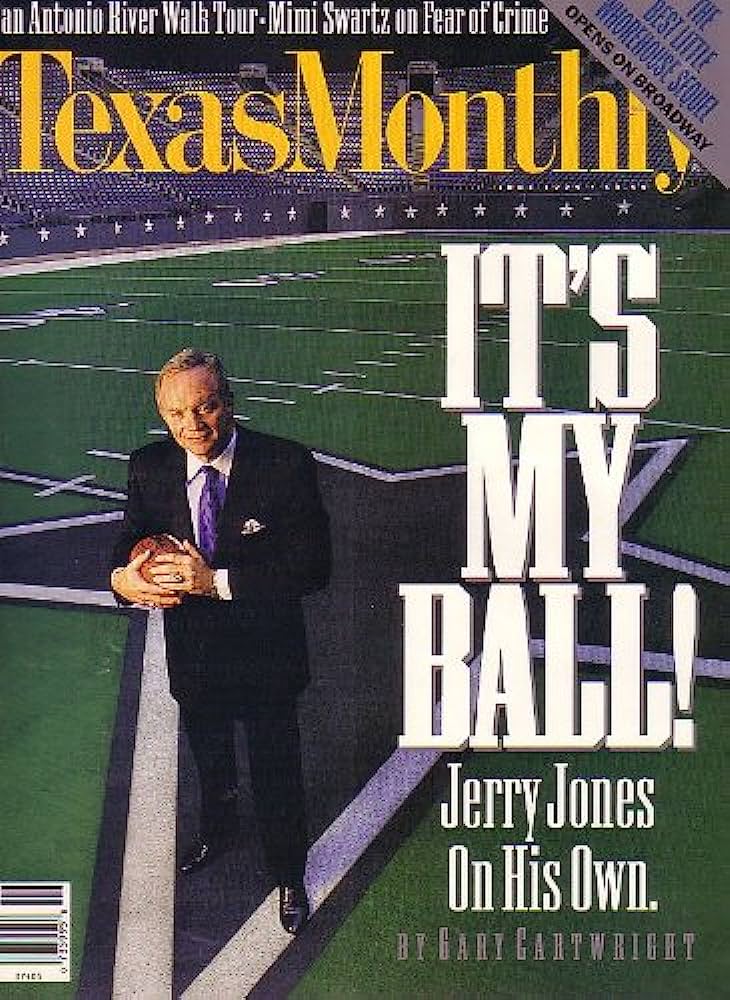

Texas Monthly cover, June 1994…

Add Comment