The mean streets of south Dallas, where Duane Thomas grew up, are not far from the Cotton Bowl, and he surely dreamed about playing football there. He had starred at Lincoln High School, but this was at the tail end of the segregation days and Southwest Conference recruiters ignored him. Just as another deserving Lincoln grad, Abner Haynes, had to settle for North Texas State a decade earlier, Thomas accepted a scholarship offer from West Texas State. He gained 2,418 yards (6.0 yards per carry) and scored 20 touchdowns for the Buffaloes between 1966 and 1969.

Impressive, but could Thomas make it in the pros? The Philadelphia Eagles’ scouting report said he was talented but a troublemaker. If Gil Brandt, director of player personnel for the Dallas Cowboys, knew of Thomas’ reputation—and I’m certain he did—he was nonetheless willing to advocate for him. The other members of the Cowboys’ triumvirate, coach Tom Landry and general manager Tex Schramm, agreed to roll the dice. They selected Thomas in the first round of the 1970 NFL draft partly because their fine running back, Calvin Hill, had a badly injured toe and might not make a timely recovery.

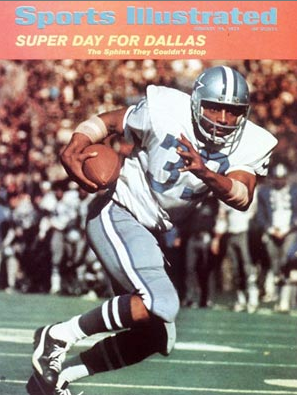

As it turned out, Hill did play the next two tumultuous years, albeit not at such a high level. He shared the backfield with Thomas, and the young guy (in fact, both were born in 1947) burst on the scene at the Cotton Bowl and then at newly opened Texas Stadium. The 6′ 1′’, 215-pound Thomas possessed skills that reminded fans of Hugh McElhenny, Jimmy Brown and O.J. Simpson—that is, he ran smoothly with a free-flowing style. While Roger Staubach, Bob Lilly, Lee Roy Jordan, Mel Renfro and others did their part in winning the NFC title and playing in Super Bowl 5, Thomas made all the difference. He gained 803 yards (a league-leading 5.3 yards per carry), scored five TDs and was second in offensive rookie of the year voting. The Cowboys lost to the Baltimore Colts in that game, but the future looked bright with number 33 an unquestioned star.

Throughout Thomas’ first year as a pro, he had done nothing to validate the Eagles’ “hands off” warning. But in fact, there was a problem. The three-year contract his agent, Norman Young, had negotiated with Schramm was not an especially good one; he earned just $18,000 in 1970, although that does not include money made from incentives. The Cowboys had a firm policy against renegotiating contracts, and they said he would have to wait until after the 1972 season for a raise.

He refused to wait. At an impromptu press conference just before the 1971 training camp in Thousand Oaks, California, Thomas scorched the franchise leaders, calling Landry “a plastic man, not a man at all,” Brandt “a liar” and Schramm “sick, demented and totally dishonest.” Schramm would later say jocularly of his put-down, “Not bad. He got two out of three.”

Things were at a standstill, with neither side willing to budge. The Cowboys, fed up, sent Thomas to New England in a five-player swap. Nearly as soon as he got to the Patriots’ camp, however, he clashed with coach John Mazur. NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle stepped in and rescinded the trade. An angry Thomas was back with Dallas, but he had taken a vow of silence. Although he practiced and played, he went into a shell. Landry tried and tried to reach some kind of understanding with his gifted running back—coddling him, some said. Landry had dealt with rebellious players before, most notably Don Meredith (Thomas “Hollywood” Henderson arrived a few years later), but never anything like this. The 1971 Cowboys were a team on the razor’s edge because of Thomas.

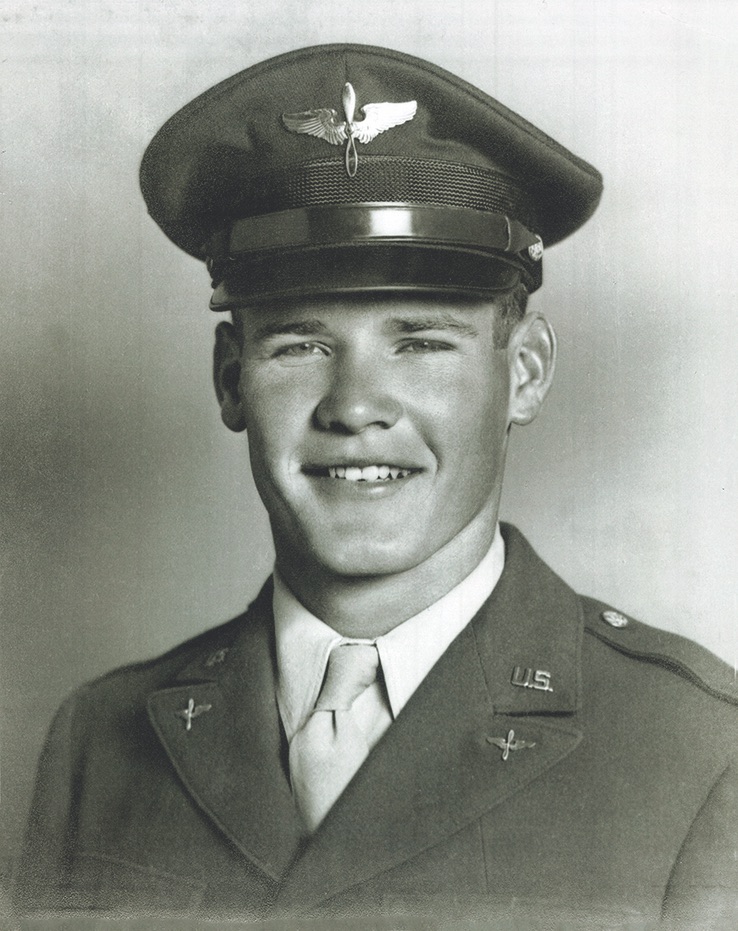

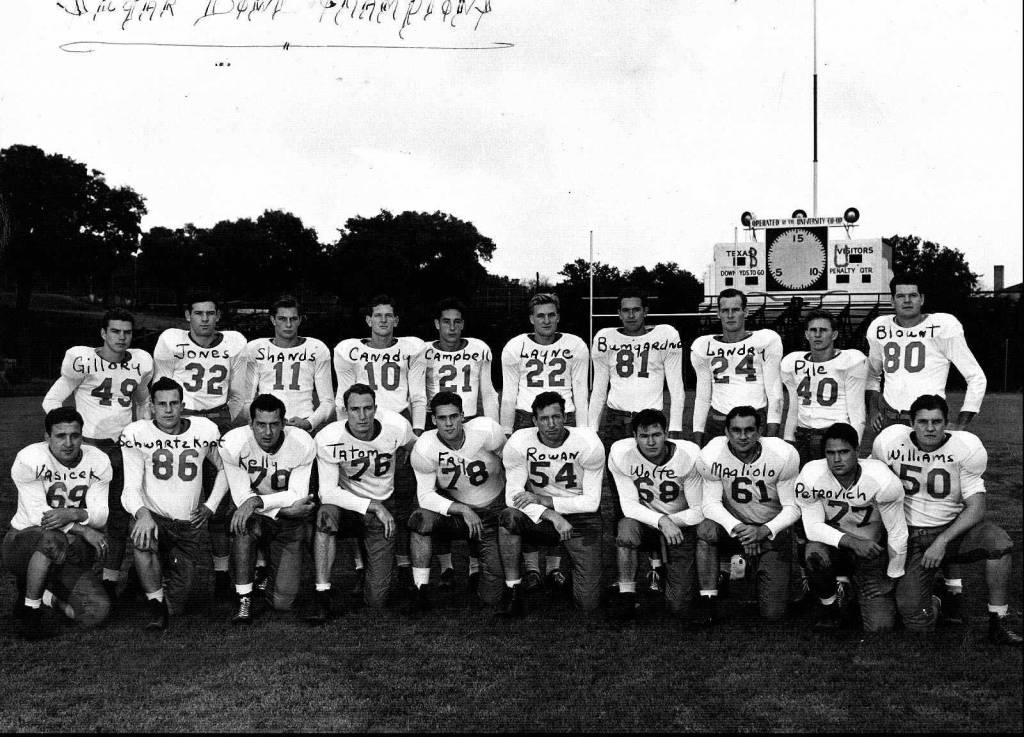

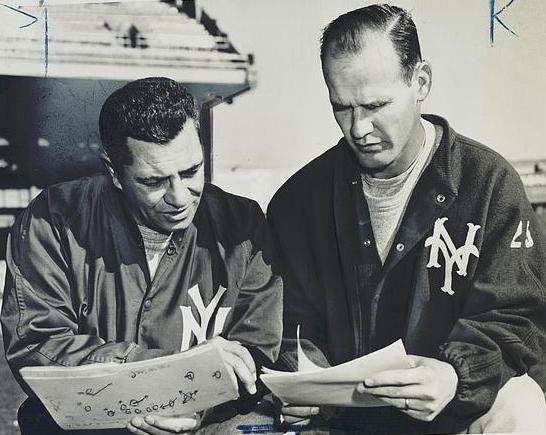

Let us now direct our attention to Landry. He had been successful at Mission High School and at the University of Texas where he majored in industrial engineering and led the Longhorns to a defeat of Georgia in the 1949 Orange Bowl. During World War II, he mastered the B-17 airplane, flew 30 combat missions and survived a crash-landing in Belgium. With the New York Giants between 1950 and 1955, Landry returned kicks, punted, and played defensive back and quarterback. Although not very fast (10.3 seconds in the 100), he scored 6 touchdowns, snagged 32 interceptions and recovered 10 fumbles. Landry served as player-coach for New York in 1954 and 1955, although he had been informally “coaching” his defensive teammates from the start. “Most of us just played the game,” said Frank Gifford. “Landry studied it.”

More can be said about Landry. He married a beautiful UT coed named Alicia Wiggs and had two daughters and a son with her; earned a master’s degree at the University of Houston (also in industrial engineering) in 1952; was a dedicated member of Highland Park Methodist Church for 43 years; turned down an offer from Bud Adams to be the AFL Houston Oilers’ first coach; drove the Cowboys to the top in the wake of President John F. Kennedy’s murder in downtown Dallas; endured the “Ice Bowl” game at Lambeau Field in 1967; and was held in high regard by his NFL peers—men such as Vince Lombardi, George Halas and Hank Stram.

Landry was sometimes criticized for his lack of emotion on the sidelines, but he insisted, “I’m not a cheerleader. I keep my head in the game…. I pattern myself after [golfer] Ben Hogan. He was always focused.”

Despite all kinds of strange scenes in the Cowboys’ 1971 season, they sparkled. Beginning on November 7, they scored consecutive victories over the St. Louis Cardinals, the Eagles, the Washington Redskins, the Los Angeles Rams, the New York Jets, the Giants and the Cardinals again. In the playoffs, they swept the Minnesota Vikings, the San Francisco 49ers and the Miami Dolphins (24-3, in Super Bowl 6). Thomas ran for 95 yards, caught three passes and scored once against Don Shula’s Fins, who would win the title the next two years. Sportswriters were overwhelmingly in favor of naming Thomas Super Bowl MVP, even though he had boycotted the media. But Sport magazine, which was in charge of the matter, feared Thomas would refuse or somehow cause a scene during the presentation, so the trophy and a sports car which went with it were given to Staubach.

Landry, who had cut Thomas far more slack than any other player in Cowboys history, was amazed that his team had won the championship under such trying circumstances. But he, Brandt, Schramm and owner Clint Murchison were in full agreement that it could not continue. The San Diego Chargers, entranced by Thomas’ running magic, were willing to trade two of their top young players to Dallas for him. Although GM/coach Harland Svare allegedly offered Thomas a six-figure, three-year contract, it did not go well. He earned a 20-day suspension for refusing to report to the team. And when he finally did, in his only appearance (against the Cowboys, of all teams) he was aloof from teammates, wandered around while the national anthem was being played and sat slouching on the bench in his high-top cleats. He did not play the rest of the 1972 season.

Hoping Thomas still had it—he was only 26 years old, after all—the Redskins sent the Chargers first- and second-round draft choices for him. During the 1973 and 1974 seasons, he played in 24 games for Washington, starting just three. He gained a total of 442 yards and scored six TDs. Thomas seemed to think that merited a substantial raise, but his employers disagreed.

He was out of the NFL all of 1975. Then, in a remarkable show of forgiveness, the Cowboys signed him as a free agent; he did not make the team. The 1977 and 1978 seasons—nothing. The Green Bay Packers gave him a shot in 1979, but Thomas was cut. His playing career had come to an end.

Thomas would later (with the help of a ghostwriter) pen a self-serving autobiography entitled Duane Thomas and the Fall of America’s Team. But the fall was his own. Hey, Dallas played in three more Super Bowls in the 1970s, winning one and losing two. And what did Thomas do during that time? He went through a divorce, was busted for marijuana, filed for bankruptcy and sold his Super Bowl ring for $8,000. In later years, he tried acting, selling medical equipment, running a travel agency, doing carpentry, growing avocados and teaching yoga. He gave lots of interviews in which he mixed honest regret, blame of others and odd philosophical musings.

I know of no pro athlete who has more completely thrown away his career. It was painful to see Thomas, with a woefully skewed perspective, mishandle things. Playing in his hometown, for a glamour NFL franchise and running behind a superb offensive line, he was in an almost ideal situation—one he could have and should have capitalized on. Thomas ought to have been more patient and mature, and less stubborn and adversarial. Football is a team game, and a guy has to sublimate his ego a bit. The Cowboys knew Thomas’ value after the 1970 and 1971 seasons, and they surely would have given him a better contract (despite their official policy), obviating the three-year deal he signed out of West Texas State. Instead of slinging insults at his bosses and then playing the sphinx, he could have sought guidance and support from his head coach. Landry, 270-178-6 over 29 seasons with Dallas, was not a rigid, ice-cold person as critics asserted. He demonstrated considerable flexibility in dealing with his temperamental running back. I have no doubt that he (and Schramm and Murchison) would have tried to facilitate a long and lucrative career for Thomas. That would have been better for all concerned.

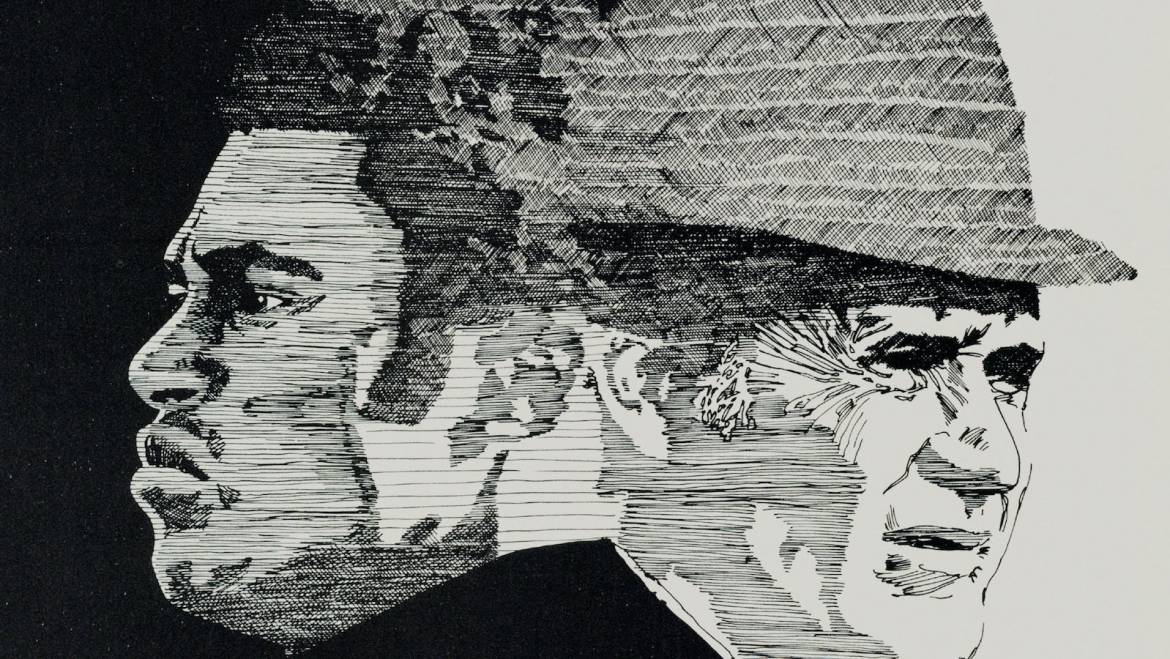

Second lieutenant Tom Landry, US Army Air Force.

New York Giants assistant coaches Vince Lombardi and Tom Landry, circa 1957.

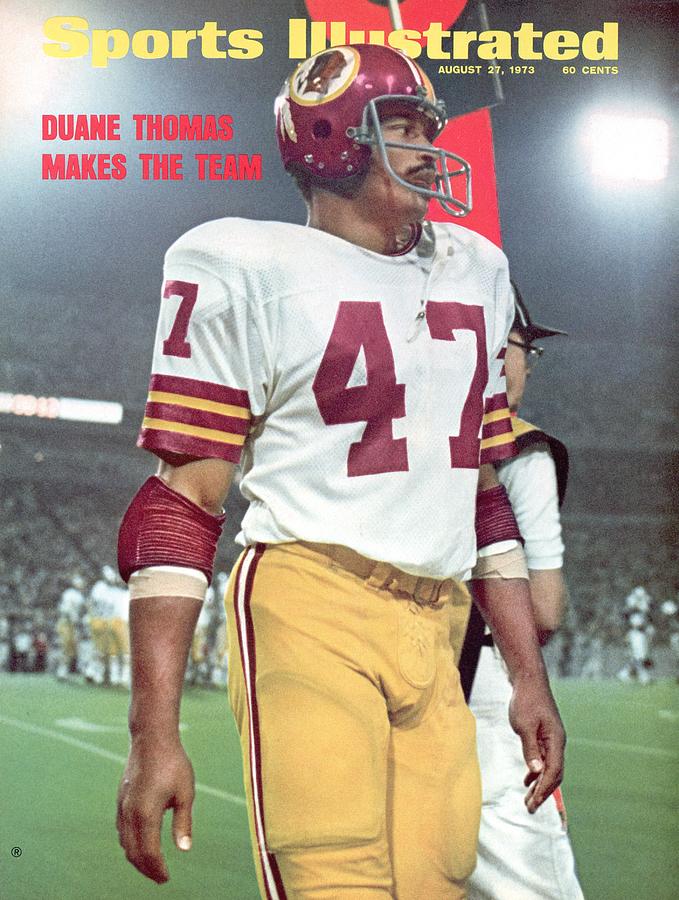

Duane Thomas graces the cover of Sports Illustrated after Dallas’ victory in Super Bowl 6.

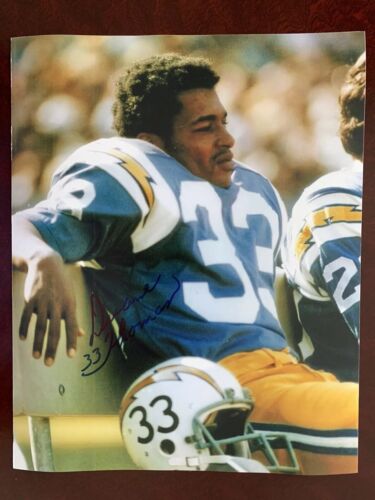

A slouching, uninterested Thomas in his one NFL game in 1972.

Thomas with the Washington Redskins, 1973.

4 Comments

great article I recall all the events of duane thomas. brockway and I went to the superbowl in New Orleans against miami and what a great game he had. of interest were you aware he mentored both personally and in the game by jim brown. and the famous interview after the superbowl in the locker room by I’m not sure what famous announcer he broke his silence when he was asked the question with Jim brown standing at his side , “what was it like to have just played in the ultimate football game?” and duane responded with “if it’s the ultimate game why do they play it every year?” end of interview. again great article as always

Billy: Yes, I am aware of Brown at the SB. The TV guy was Tom Brookshire, who asked the stupid question, “Are you that fast?” Thomas stared at him for 10 seconds and finally said, “Evidently.” I chose not to use it in this article.

Nice article, Richard, and a sad story of unrealized potential.

Thank you, Mike. You said something I should have said–about Thomas’ unrealized potential. Very good point.

Add Comment