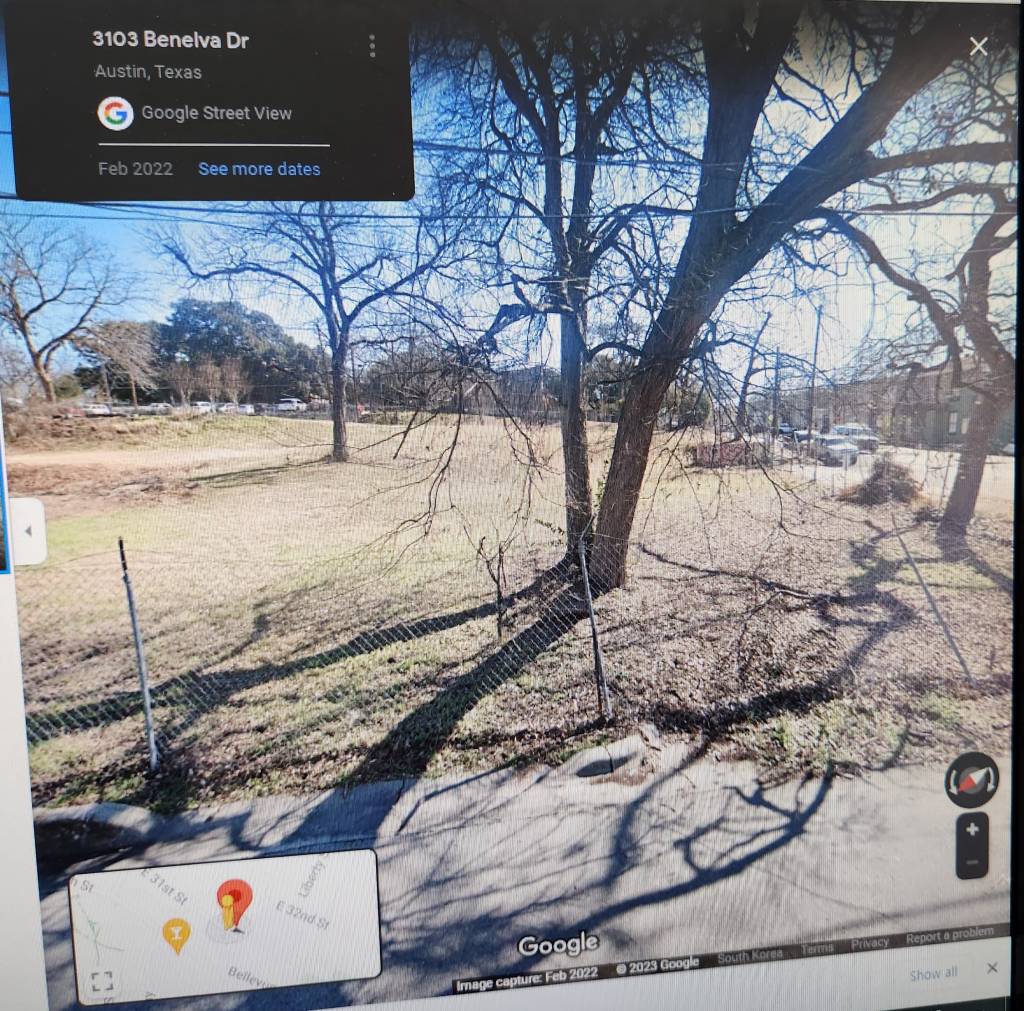

A few blocks north of the UT Law School sits 3103 Benelva Drive. Now a vacant lot, it held an old wooden duplex with a carport when I lived there in 1982. The ground-level apartment in which I resided was quite small. My friend Brian Ullom visited once and stated that he could imagine somebody committing suicide there. His assessment seemed a bit harsh because I remember that time with fondness, and not once did I consider performing self-slaughter.

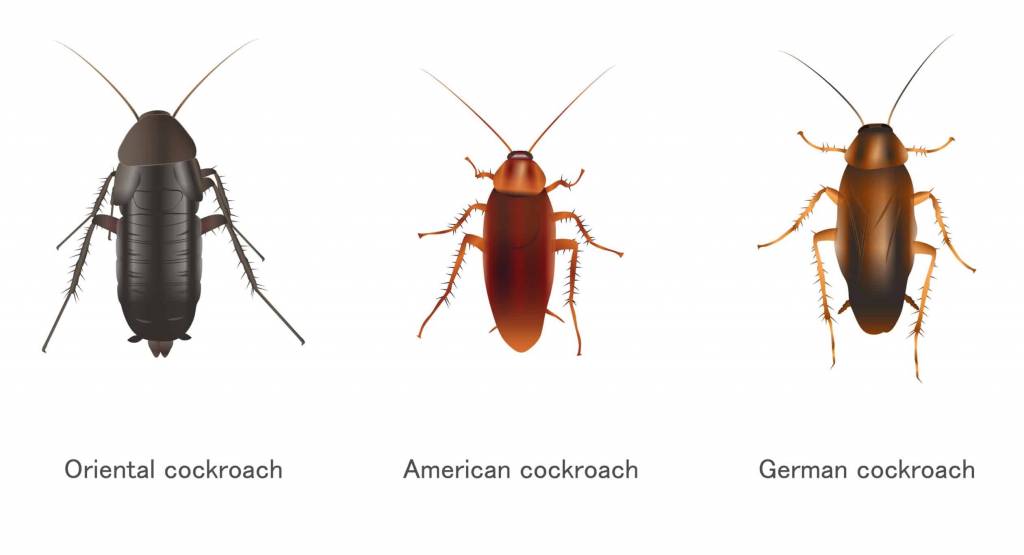

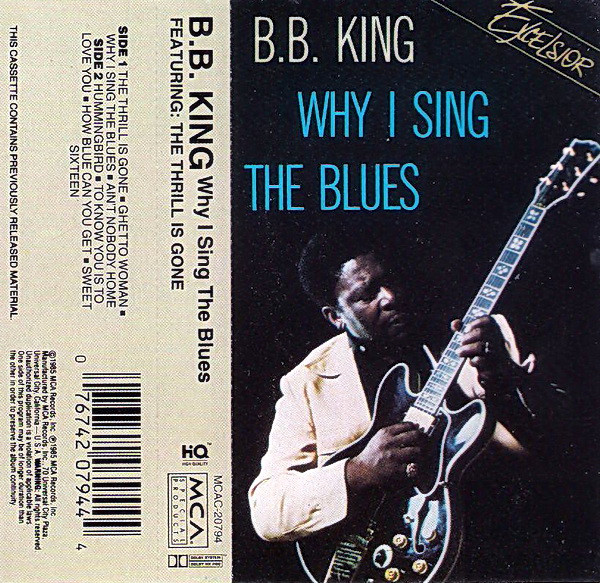

I lived alone. Well, not exactly alone, since my humble abode was infested with cockroaches. Two lines from B.B. King’s 1974 song “Why I Sing the Blues” go this way: “I’ve laid in a ghetto flat, cold and numb / I heard the rats tell the bedbugs to give the roaches some.” It wasn’t a ghetto, and I recall no rats or bedbugs. But roaches? There was an abundance of them, a profusion, a veritable plethora. I am telling you, 3103 Benelva was teeming with cockroaches. Our planet has more than 4,600 species of the hardy cockroach, and it has been around for some 320 million years.

Perhaps you are aware of Ahimsa, the ancient Indian principle of nonviolence toward all living beings. Humans, it holds, are no more important than cattle, three-toed sloths, butterflies—and cockroaches. Jains, Hindus, Buddhists and Sikhs believe that in the next life, we might just be on the lower end of the scale. So, best to treat them kindly. It is a nice philosophy, and I adhere to it in a general way. I paid the rent at my apartment, however, and did not want to have cockroaches as roommates. That meant a daily and nightly battle between me and these ugly, winged insects.

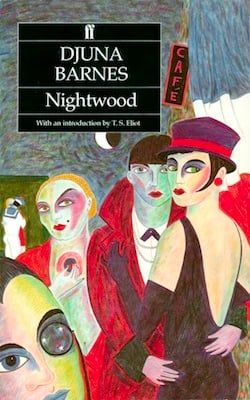

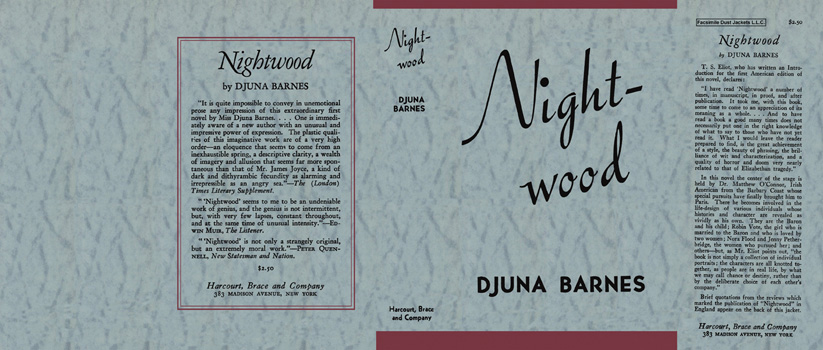

My job then consisted of washing dishes at the Capitol Oyster Bar. One of the waitresses there, an artsy red-haired woman named Robin, “gifted” (I am using the nounized verb consciously) me a paperback book: Nightwood by Djuna Barnes. Surely the best-known native of Stone King Mountain, New York, she lived from 1892 to 1982—the same year in which these events transpired. The avant-garde Barnes was revered and feared for her wit and intensity, charm and moxie. She once interviewed James Joyce and stated—in print—that she found him boring. Barnes, who has been called the literary patron saint of bohemia, wrote poetry, plays and short stories, but her enduring fame can be attributed to Nightwood. An alcoholic, she lived mostly in Manhattan, London, Paris and North Africa. Her final 41 years were spent as a semi-recluse in a smoke-filled Greenwich Village garret.

Why Robin gave me this book, I do not know. I almost never read fiction, and its topic—lesbian love—was not likely to grab me. The novel was a roman à clef which featured a thinly veiled portrait of Barnes in the character of Nora Flood, whose romantic interest was Robin Vote (in real life, a GF of Barnes’ named Thelma Wood). The main themes of Nightwood are jealousy, infidelity, violence and drinking. This book, which sold poorly after its publication in 1936, is highly regarded; Dylan Thomas considered Nightwood “one of the three great prose books ever written by a woman,” and William Burroughs said it was “one of the great books of the twentieth century.” I am told that it is now a cult classic.

Be that as it may, I was not inclined to read Barnes’ masterpiece. But it did serve another purpose during my stay at 3103 Benelva. I used it to kill as many of my co-tenants as possible. Whenever I saw one, I grabbed the book, rolled it up and came at the offending bug with bad intent, applying maximum force. I must have sent hundreds of cockroaches to cockroach heaven by such means. And in nearly every instance, I would holler the words “Nightwood…Djuna Barnes…whack!”

Try to imagine the condition of that book before I moved out of my bungalow and into a larger—and bug-free—place even closer to the law school. Whenever I performed one of these executions, some cockroach corpse remained. It was beyond nasty. It was disgusting.

Add Comment