In President Richard Nixon’s memoirs, he wrote thus of Charles Colson: “His instinct for the political jugular and ability to get things done made him a lightning rod for my own political frustrations…. When I complained to Colson, I felt confident that something would be done. I was rarely disappointed.”

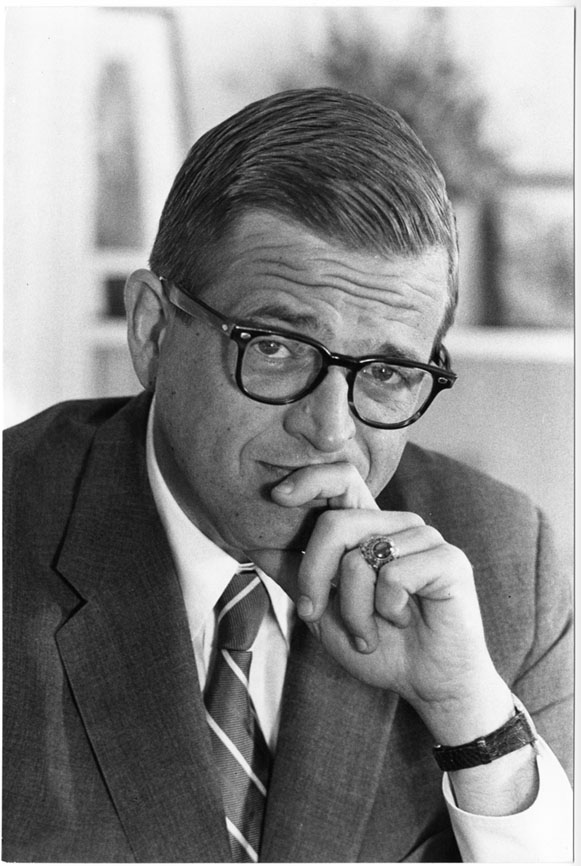

Among Nixon’s Watergate scoundrels—Colson, G. Gordon Liddy, E. Howard Hunt, John Dean, John Mitchell, H.R. Haldeman, John Ehrlichman, Jeb Magruder, et al.—he was the most infamous. Colson, a man of formidable drive, intellect and energy, was a ruthless player of power politics. A tough-as-nails fellow with a talent for incisive repartee, he was deeply loyal and sometimes boasted that he would run over his own grandmother to help the 37th president.

Rather like George H.W. Bush, he was a New Englander who went to private schools and then studied at an Ivy League college. A Marine Corps captain and founder of a successful law firm, Colson first met Nixon in 1956. He commiserated with him after the close defeat in the 1960 presidential campaign and again after the 1962 California gubernatorial race. As soon as Nixon reached the White House in 1968, he hired Colson as his special counsel. Who better to compile Nixon’s enemies list? Colson orchestrated the 1971 “hard-hat riot” in New York City and was peripherally involved in the planning and cover-up of a bungled break-in at the Democratic Party’s headquarters in the Watergate complex in Washington, DC on June 17, 1972.

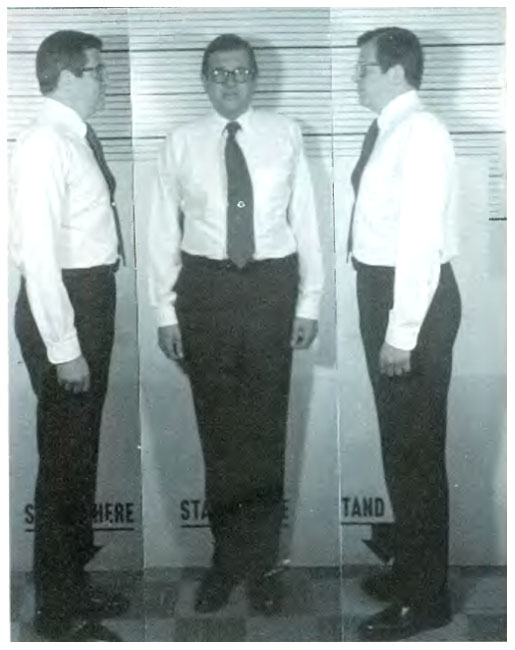

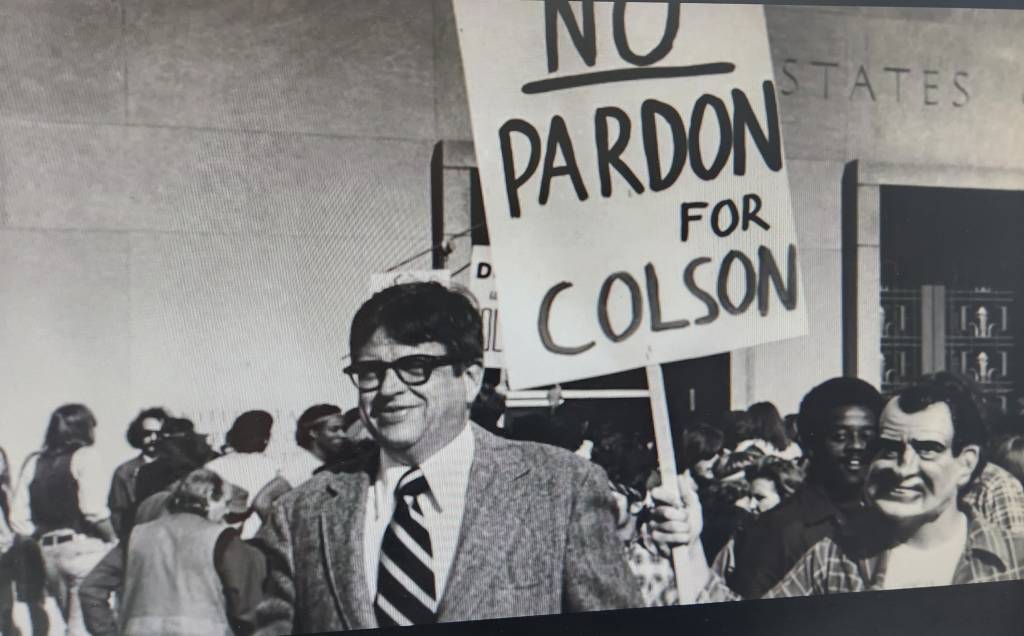

What got Colson in trouble, however, was his attempt to defame Daniel Ellsberg and influence his trial for having released the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times; Ellsberg’s case was thrown out as a result. Indicted, he went against his lawyers’ advice and pled guilty to obstruction of justice. Nixon’s one-time hatchet man was disbarred and given a five-year sentence (although he would serve just seven months at a minimum-security prison in Alabama). His subsequent testimony before the Watergate panel contributed to Nixon’s downfall and resignation in August 1974.

Before Colson entered Maxwell Federal Prison, a colleague gave him a copy of C.S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity. That fine book—I read it many years ago—led to a soul-shaking encounter with the Prince of Peace. Colson joined a Bible study and prayer group consisting of both Republicans and Democrats. He made public his new-found belief, and I can still remember how people scoffed. Time, Newsweek, The Village Voice and other media outlets howled and called it a brazen attempt to have his sentence reduced.

Others have done that, I realize, but Colson’s “conversion” was 100% authentic. From late 1973 until his death on April 21, 2012 from a brain hemorrhage, he was nothing if not consistent. The way he talked, acted and lived demonstrated true Christian faith.

There is another criminal, far more notorious than Colson, whose turn from darkness to light has always impressed me. I refer to Charles “Tex” Watson, one of Charles Manson’s fanatical and drug-addled killers in Los Angeles in the summer of 1969. Watson’s subsequent admission of guilt and his manner of speaking as an honest Christian rings true, although many people cannot bear to forgive him.

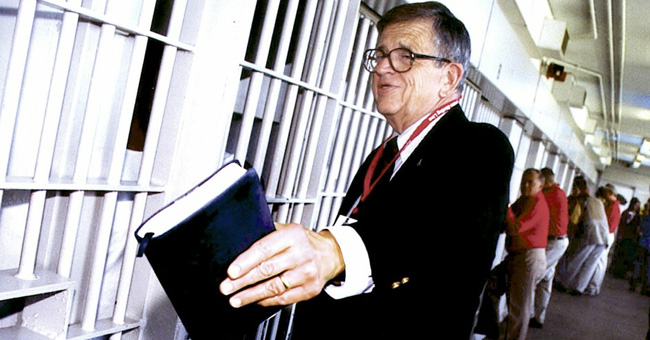

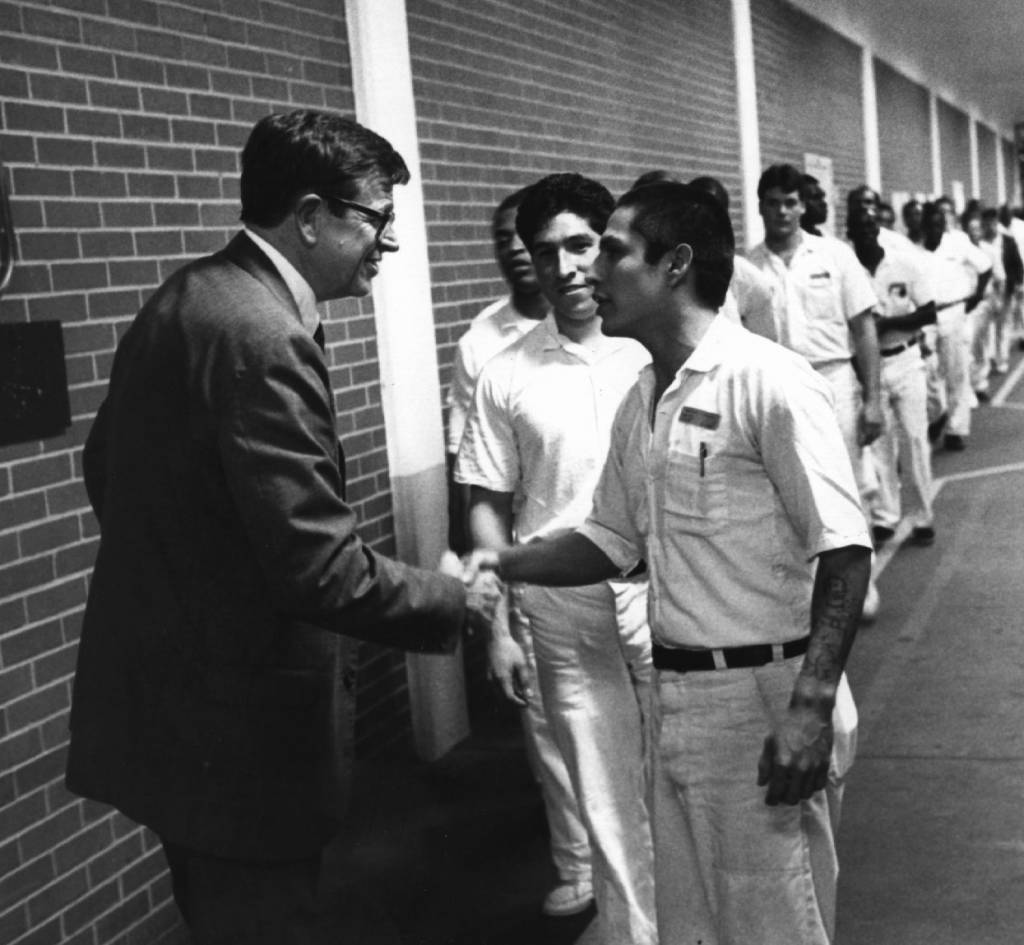

During his incarceration, Colson (inmate number 23227) got a close look at prison injustice, poor rehabilitation and the “lock and leave” philosophy in which prisoners were warehoused. On a three-day furlough for the funeral of his father, Wendell, he remembered that the old man had been involved in prison reform. Colson felt called to develop a ministry and wasted no time in doing so. He created Prison Fellowship International, which came to have a staff of 280 and 50,000 volunteers working at 800 prisons in 112 countries. The former master of dirty tricks sought to improve prison conditions, reduce recidivism and eliminate the death penalty in all but the most egregious cases. He advocated alternatives to prison for nonviolent offenders, as well as restorative justice which focused on healing broken relationships, repairing the damage done by crime and helping offenders find a meaningful role in society. It’s easy to see why inmates lined up to shake his hand.

He created entities other than PFI and wrote 30 books, including Born Again (1975), Life Sentence (1979), Kingdoms in Conflict (1987), How Now Shall We Live? (1999) and My Final Word (published posthumously in 2015). Colson gave speeches, did radio broadcasts and went back inside prisons to inspire, encourage and pray with the men and women still behind bars. He got 15 honorary doctorates and won the 1993 Templeton Prize for contributions in affirming life’s spiritual dimension (other Templeton laureates include Billy Graham, Mother Teresa and the Dalai Lama); the $1 million was donated to PFI, as were all his royalties.

Colson called for cooperation between Protestants and Catholics. But he also addressed a variety of contemporary and cultural issues. He was, for example, a critic of postmodernism who sought a foundation of moral absolutes. While I agreed with most aspects of Colson’s program, his opposition to abortion and gay marriage had no real meaning for me. Also, he doubted evolution, which Charles Darwin and others proved about 150 years ago; thinking Christians have no choice but to reconcile their faith and evolution. I was disappointed to learn that he never apologized to Ellsberg and did not respond to Ellsberg’s efforts to get in touch. Colson may have been a righteous and genuine Christian, but he was not perfect.

The life of Charles Colson was one of a remarkable reversal, from Nixon’s political saboteur to prison inmate to spiritual guide. “I shudder to think what I would have been if I had not gone to prison,” he said in 1993. “Lying on the rotten floor of a cell, you know it’s not prosperity or pleasure that’s important but the maturing of a soul.”

2 Comments

As a theme in literature, movies, or everyday life, redemption hits home with this flawed Lutheran. Have I sinned? I could run through the English alphabet and use all 26 letters to begin the names of my misdeeds. (Yep, I’ve even been guilty of xenophobia.) When Jesus said, “Go, and sin no more”, Mr. Colson took those words to the depths of his heart and mind and ACTED upon them. Phonies don’t go to the ends of the Earth; Chuck Colson did in the literal sense. We are justified by faith but must act to bring positive change to this miserable planet. God bless him and also Richard.

Thank you, Dex….you are far more eloquent than I!!!

This deep respect for Colson had been running around my mind for so long….time to write about it

thank you again

Add Comment