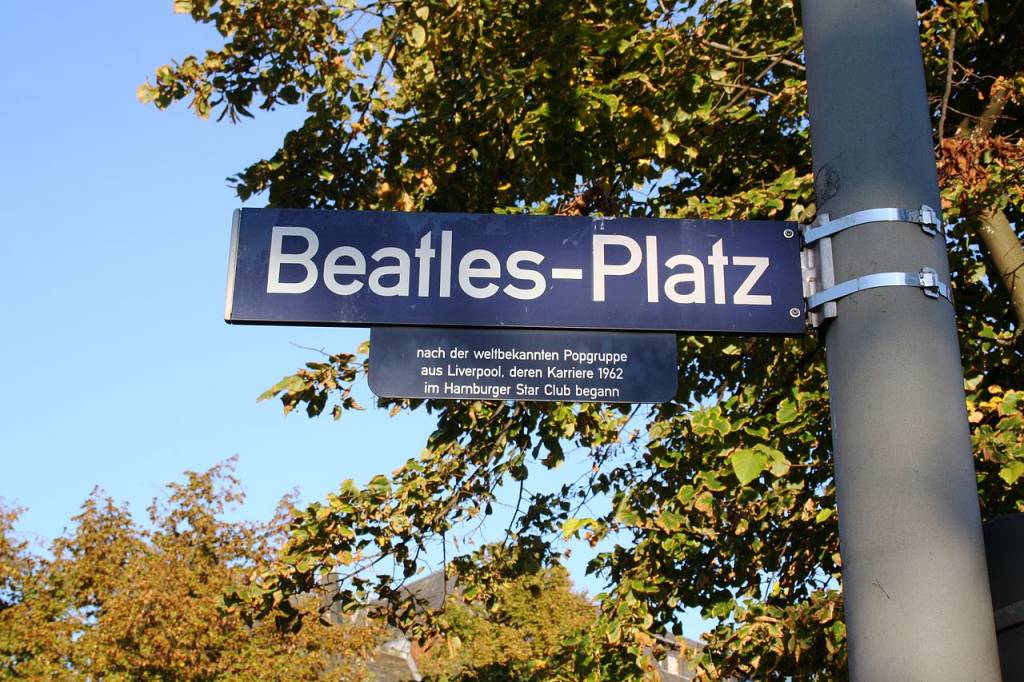

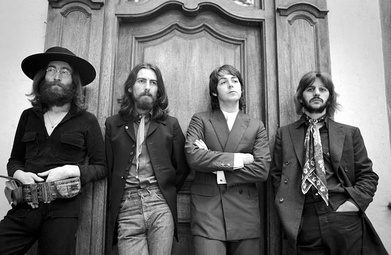

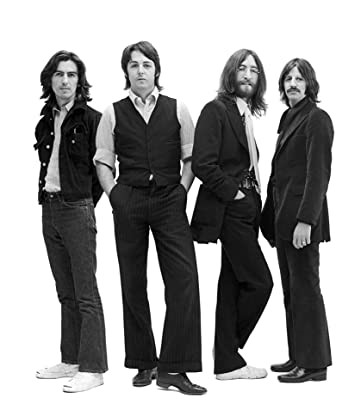

In May 1959, John Lennon, Paul McCartney and junior partner George Harrison started calling themselves the Beatles. They appeared at Lennon’s art college, churches and wherever else they could plug in their equipment and play covers of the songs of Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, Little Richard, et al. It seems that their first legitimate show was at Litherland Town Hall on January 5, 1961. They also played in Hamburg’s Reeperbahn district at such venues as the Indra, the Kaiserkeller, the Top Ten and the Star Club. Growing musically and as showmen with four stints in that rough port town, they had unveiled such Lennon/McCartney songs as “Please Please Me” and “Love Me Do.” When the Beatles returned to the UK in early 1963, they were on the verge of a breakthrough in the form of a recording contract and the massive popularity known as “Beatlemania.” By that time, Ringo Starr was the drummer, secondary bassist Stu Sutcliffe (who in truth couldn’t play a lick) had departed, and Brian Epstein was operating as the band’s manager.

The issue here is public performances. The Beatles are estimated to have taken the stage more than 1,500 times in places as varied as the Beach Ballroom in Aberdeen, Scotland; Royal Albert Hall in London; the Odeon Cinema in Llandudno, Wales; the Boråshallen in Borås, Sweden; the Ritz in Belfast, Northern Ireland; the Olympia Theatre in Paris, France; CBS Studio 50 for the Ed Sullivan Show in New York; the Princess Theatre in Hong Kong; Centennial Hall in Adelaide, Australia; Memorial Auditorium in Dallas; Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto, Canada; Velodromo Vigorelli in Milan, Italy; and Nippon Budokan in Tokyo, Japan.

Lennon, McCartney, Harrison and Starr had been on the road almost nonstop for 3 1/2 years, and they were exhausted. In the final two months, they’d had all sorts of problems in Manila (somehow offending first lady Imelda Marcos), Memphis (where Lennon’s “we’re bigger than Jesus” comments were not well appreciated), Cincinnati (a canceled concert due to heavy rain, although they played the following day), St. Louis (more rain and a half-empty stadium), Los Angeles (fans rushing the stage only to be repulsed by billy clubᅳwielding cops) and San Francisco (cold, windy and foggy, as was often the case at Candlestick Park). They led off with “Rock and Roll Music,” followed by “She’s a Woman,” “If I Needed Someone,” “Day Tripper,” “Baby’s in Black,” “I Feel Fine,” “Yesterday,” “I Wanna Be Your Man,” “Nowhere Man,” “Paperback Writer” and “Long Tall Sally.”

The date of that San Francisco gig was August 29, 1966. Although no formal announcement was made, Lennon, McCartney, Harrison and Starr agreed that they would not go on tour again. The reasons were many: The sound systems were woefully inadequate to play in big arenas, the screaming teenage fans had come to bore them, they sensed increased negativity from the press, they had seen their musical skills degrade, and they were having no fun whatsoever. Compounding matters, they all had more than enough money to last the rest of their lives. Why go back on the road if they could just stay in the studio and make albums like Revolver, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, The Beatles (the “White Album”), Yellow Submarine, Abbey Road and Let It Be?

In many ways, it’s hard to blame the four Liverpudlians for this decision. They had, no doubt, earned the right to do as they pleased. The aggravations of touring had long eclipsed its pleasures. Over the next 2 1/2 years, they reveled in youth culture—God knows that was flourishing in the late 1960s—, did a couple of film and TV projects of no great significance, formed a money-losing entity called Apple Corps, had copious sexual partners, went to India to see whether Maharishi Mahesh Yogi could teach them to transcendentally meditate (he failed) and consumed drugs; Lennon, McCartney, Harrison and Starr partook of speed, weed, cocaine and LSD. Lennon dabbled in heroin as well.

As much as anything, however, they bickered. Harrison had resented being relegated to secondary status by Lennon and McCartney even in their Liverpool and Hamburg days. Starr, too, had been abused by the two big boys. (Nor was the drummer happy with Harrison for having engaged in an affair with his wife Maureen.) Lennon and McCartney were at each other’s throats more often than not. If McCartney was the glue holding the band together in those final years, he had nonetheless earned the enmity of the other three. It was clear to those around the Beatles (Neil Aspinall, Malcolm Evans, Derek Taylor, Peter Brown and George Martin) that a final break was inevitable. They last played together in the studio on August 18, 1969, and McCartney issued a press release in April 1970 stating that Lennon’s call for a “divorce” had been granted, although the formal dissolution did not come until December 1974.

You may recall that as part of the Let It Be project, on January 30, 1969 they climbed atop the Apple headquarters on Savile Row and played a six-song set. On hand were friends, acquaintances and some Apple employees, so that hardly counts as a concert. The Beatles often said, and I suppose it’s true, that the music they were making in the studio could not have been duplicated on stage, in front of an audience. “A Day in the Life” included a 40-piece orchestra, as an obvious example. Numerous other musicians had contributed to their later albums—violinists, flautists, saxophonists, oboists, clarinetists, guitarists, percussionists, and vocalists both male and female.

But I have to think the Beatles felt more than a little envy when they saw British bands like the Rolling Stones, the Who and Led Zeppelin tearing it up before big, adoring crowds. Sound systems and security had improved since their USA tour in the summer of 1966. Lennon, McCartney, Harrison and Starr later mentioned stage fright as one reason for their hesitation to go back out in public. Stage fright? These guys had done it 1,500 times before, and they never seemed at all hesitant, shy or fearful. I suggest that rather than withdrawing into a cocoon of sorts, the Beatles could have limited the number of shows, dictating what, where, when, how—everything. They also might have asked Billy Preston, a fine black keyboard player and singer who took part in the so-called rooftop concert, to join the band. That would have really taken the Beatles in a different direction.

#beatles, #johnlennon, #paulmccartney, #georgeharrison, #ringostarr, #rockmusic, #rooftopconcert

6 Comments

There’s a lot to say about the Beatles, but I say : ,,The best ,, and with that I think I’ve said it all.

Thank you for sharing wonderful memories of the past with us.

They were the best, Elly. You are right about that!

Some damned good writing, Richard. Never a Beatles fan, I enjoyed and learned from your essay. During their heady days, who knew of the enmities that were eating away at the band? By the way, you got in a great musical pun: “…secondary bassist Stu Sutcliffe (who in truth couldn’t play a lick)….”

Thanks for enriching my knowledge while branding your trademark sense of humor.

Not a Beatles fan? Peeps like you were rare. Even so, all this cultural history…. At the end, they could not stand each other!

Richard,

Nice article about a favorite subject from my formative years. I was never a musician nor was I a music critic, but I know what I liked — and I loved the Beatles. Certainly in my Top 3 group of all time.

Excellent research. I’d never heard that about Stu Sutcliff. Is that true, or were just being a bit snarky about our boy Stu, who shares a place in history with Pete Best. I guess Pete and Stu will always be remembered as the unluckiest musicians of all time, right up there with the orchestra on the Titanic’s maiden voyage.

Hope you’re doing well.

Oh it was true about Sutcliffe. He would even turn his back to the audience so nobody could watch his fingers on the guitar. Sad, but the guy was up on stage faking it….

Your point about Pete Best, I agree. Was Ringo such an improvement? He paid his dues, and just when the good times were about to start he was OUT.

Add Comment