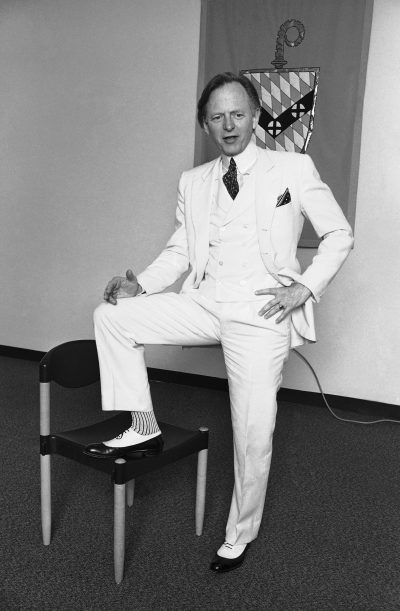

Starting in my college days, I read The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, Radical Chic and Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers, The New Journalism, The Painted Word and The Bonfire of the Vanities, and enjoyed each one. I was among Tom Wolfe’s biggest fans. Wolfe, that Virginia-born writer with a BA from Washington & Lee and a doctorate from Yale, was quite a dandy. His colorful prose was matched by the bespoke white three-piece suits he famously wore, supplemented by a high starched collar, a silk tie, a bright hanky in the breast pocket, a fob watch and faux spats. But when I think about one of his other books—The Right Stuff—I want to grab him by his skinny throat, bitch-slap him and make him cry. I would do that, but it’s too late since he succumbed to nature’s demands in 2018.

The Right Stuff was about the Mercury astronauts (Scott Carpenter, Gordon Cooper, John Glenn, Virgil “Gus” Grissom, Walter Schirra, Alan Shepard and Donald “Deke” Slayton) and the unspoken code of bravery and machismo that made them ride on dangerous rockets into outer space. As Wolfe indicated, the media somehow chose the loquacious Glenn and Shepard as the superstars of the group. Most prominent among the American pilots who did not make the cut was Chuck Yeager, a World War II ace and the first man to break the sound barrier. Yeager, with only a high school education, was ineligible. He did not hesitate to assert that what those first astronauts did was passive and hardly constituted “piloting.”

Wolfe may have been a careful journalist, but he liked to spin tales. He was enamored of Yeager, and it served his purpose to find a suitable foil. That would be Grissom, portrayed as a small (he was 5′ 7″, not a disadvantage in those early, cramped cockpits), plodding and a slightly incompetent flyer. Other than his height, the characterizations were inaccurate. Grissom earned an engineering degree from Purdue University and flew 100 combat missions during the Korean War. He was cited numerous times for his superlative airmanship and did some Yeager-style test piloting; he, too, liked to go “higher and faster.” In 1959, the nascent U.S. space program, with 508 candidates for its Project Mercury, winnowed that down to 110, then to 39 and finally to 7. Grissom was fully deserving of inclusion.

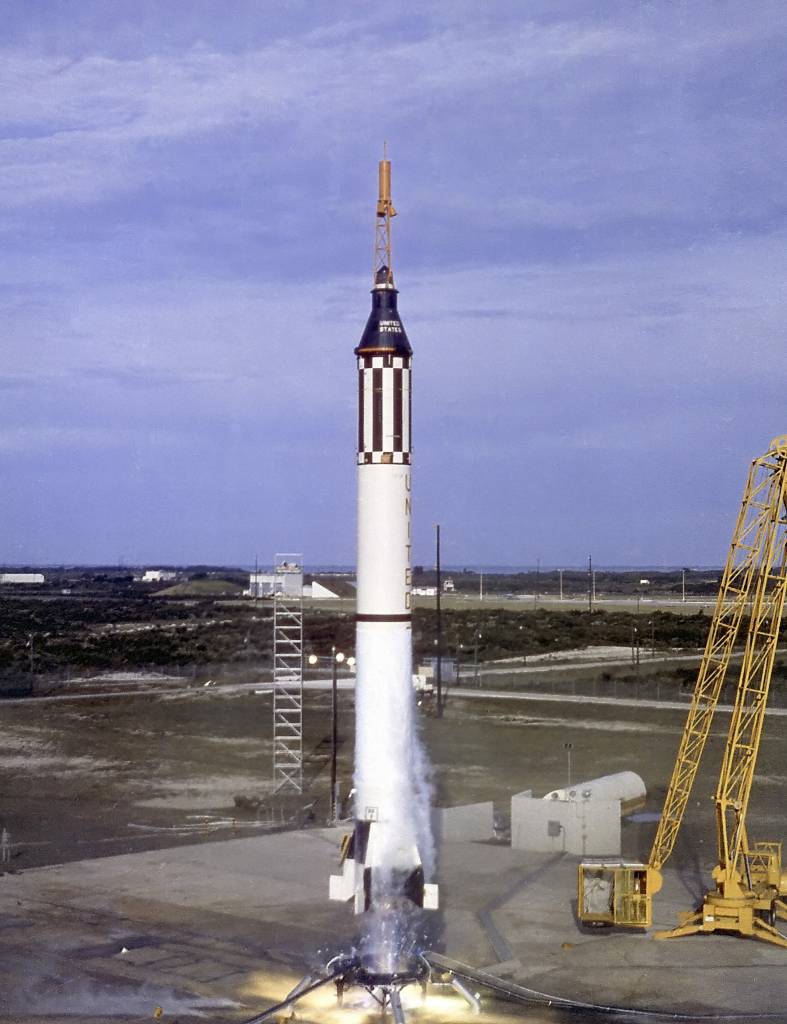

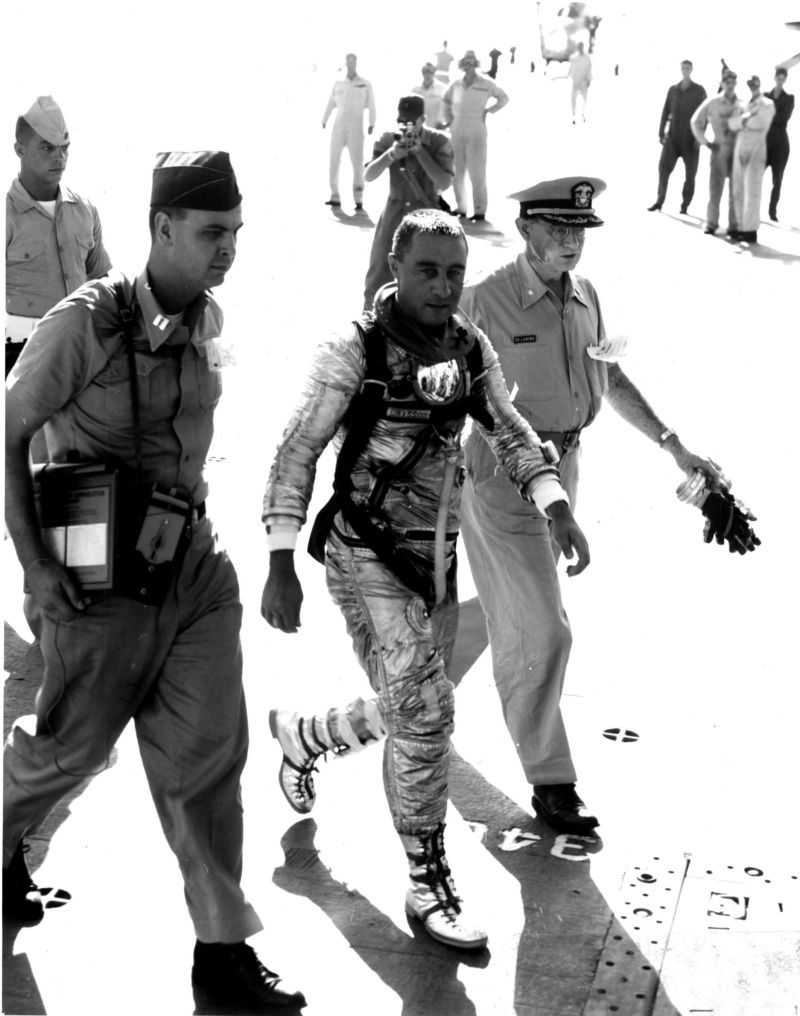

On July 21, 1961, he was the sole pilot of Mercury-Redstone 4, which he called Liberty Bell 7. That 15-minute suborbital flight went off without a hitch, as he experienced weightlessness, tested an autopilot system, made navigational observations, endured 10 G’s during re-entry and splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean, 300 miles east of Cape Canaveral. Grissom deployed a 22-foot whip antenna to help two Marine helicopters locate him. But something unexpected happened when the hatch popped open, water started to rush in and Grissom had to get out. As his space suit filled with water, he struggled to avoid drowning and still tried to help connect a cable to allow the spacecraft to be raised. After a five-minute struggle, he and Lieutenant John Reinhard reluctantly cut it loose; Liberty Bell 7 sank three miles to the bottom of the sea. Reinhard dropped a horse-collar lifeline to Grissom, he was pulled up to the copter and was then flown to the nearby USS Randolph.

The criticism and second-guessing of Grissom began almost immediately. He was—unofficially—blamed for the premature blowing of the hatch and the ship’s ignominious sinking. Compare the brief and perfunctory phone call he got from President John F. Kennedy with the ticker-tape parade John Glenn received in Manhattan’s “canyon of heroes” on March 1, 1962. The New York Times took the lead in scapegoating Grissom, despite his denial of having intentionally or accidentally made the hatch blow. His fellow astronauts stood by him, pointing out that the exploding hatch was a new feature that had not been well-tested. Grissom, a cool professional, had shown no sign of distress or panic during the flight.

Determined to salvage his reputation, he stayed with NASA and helped out on the other Mercury excursions. His bosses (Chris Kraft, John Hodge, Gene Kranz and Slayton, retired from flying due to a medical condition) appreciated that and named him the commander of Gemini 1, which he and John W. Young flew on March 23, 1965. Over a period of nearly five hours, they made three orbits of the earth. It was the first time a spacecraft had been maneuvered, by means of thrusters, an important step if the Americans were to reach the moon. That, you recall, had been JFK’s ambitious pledge shortly after his inauguration.

Grissom was also chosen to command the flight for the first Apollo mission, set for February 21, 1967. But problems abounded. The spacecraft was badly built, in spite of Grissom’s having been involved in its design and demanded numerous safety features. He, Ed White and Roger B. Chaffee were to embark on a 14-day mission. First, however, there would be a dress rehearsal known as a “plugs-out” test on January 27. Grissom played the good soldier but nonetheless frankly expressed his concerns. Schirra felt the same way, even urging him, White and Chaffee to refuse to get into what he considered a death trap. (Doing so, Schirra knew, would have signaled the end of their careers as astronauts.) Miles of poorly insulated wiring in a 100% oxygen cabin spelled potential trouble. A combination of oxygen and nitrogen would have been safer but also heavier, one of numerous indications that crew safety was a secondary issue. A catastrophic 25-second fire erupted, killing all three. I bring it to your attention that Grissom, White and Chaffee had done nothing to cause the fire, but they fought furiously to escape. It is ironic that the hatch on Grissom’s first spacecraft opened without a touch but that on his third and last would not budge.

Grissom and Chaffee were buried at Arlington National Cemetery and White at West Point, with full military honors. Craters on the far side of the moon carry the men’s names.

Twelve years after the horrendous blow-up on Cape Canaveral’s pad 34, The Right Stuff was published. (An even less factually based movie of the same title came out in 1983.) Wolfe depicted Grissom as a hard-luck astronaut and pinned the sinking of Liberty Bell 7 in 1961 on him. We now know that is almost surely not correct. Based on new digital enhancements of photographs taken that day and a re-examination of the historical record, researchers George Leopold and Andy Saunders have concluded that an electrostatic discharge generated during the unsuccessful attempt to haul the spacecraft up caused the hatch’s premature detonation.

Helicopter crewman John Reinhard, who died in 2020, told another researcher, Rick Boos, that he observed an electrostatic arc when he sought to cut the whip antenna. Almost immediately afterward, the hatch blew and skipped out onto the water followed by Grissom. Lieutenant James Lewis, who manned the other helicopter, corroborated Reinhard’s recollections after seeing the digitally enhanced images. The recovery operations generated a static shock that made the hatch’s 70 small titanium bolts fail. One of their ingredients was mercury fulminate which a NASA manual listed as a “safety concern” as it is subject to electrostatic discharge. That—not some foolhardy action inside the cockpit by Grissom—set off a series of unfortunate events.

By the way, Liberty Bell 7 was found and brought to the surface in 1999 by Curt Newport and his crack team of associates. It was fully restored, went on a national tour and is now on permanent display at Cosmosphere, a space museum and STEM education center in Hutchinson, Kansas.

Were Apollo 1 a success, Grissom might have been the commander two years later when Apollo 11 rolled around. Crew assignments were always a mysterious matter, but it is entirely possible that he rather than Neil Armstrong would have been the first of our species to set foot on the moon. Regardless of that, he was no minor-leaguer among American astronauts. Grissom was, if I may borrow the title from another of Tom Wolfe’s books, a man in full.

9 Comments

Mr. Pennington’s account of Gus Grissom’s endeavors is needed. History is full of people whose reputations were unjustly tarnished and Mr. Pennington has done his part in burnishing the Hoosier’s image.

Like Mr. Pennington, I am an admirer of Tom Wolfe’s works but always thought he was a bit flippant or even downright disrespectful of Mr. Grissom and his important role in America’s successful race to space.

It’s just a shame that Grissom died before this exoneration regarding Liberty Bell 7. He, White and Chaffee had good reason to fear getting into that cockpit, but on the other hand they went along with many of the tradeoffs along the way. One thing I did not mention was that a different entity (North American Aviation, rather than McDonnell Aircraft) was chosen because of some lobbying and politicking by Bobby Baker. A very unfortunate decision.

Oh, some people in NASA did think he had screwed up. They were proved wrong many years later. And my main point was that Tom Wolfe was wrong about Grissom.

We need accurate history and this is what you have done with this article. Gus Grissom was a trailblazer and a hero. Thanks for bringing this to my attention.

Who could relate to this better than you, a mechanical engineer? NASA was in too much of a hurry and so corners were cut. That helps explain the fiasco at the end of Grissom’s Mercury trip and this one on the launch pad for Gemini 1. Let us lay to rest any notion that Grissom was “inferior” to other astronauts. This, I think, was Tom Wolfe’s biggest mistake. If he were still alive, he might admit it.

Grissom and all other astronauts in those early days were all heroes. Not that the ones today aren’t. I enjoy your articles and you writing. Keep them coming.

I very much agree, Janene. Thanks for reading this and your comment.

RAP

I am a big Tom Wolf fan and read his books in high school and college. He heavily influenced how I write. When the Right Stuff came out I devoured it. I had wanted to be an astronaut from the age of four through 18 (college was the eye opener that ended the dream though — I never would have qualified and women weren’t even considered when I was growing up). I grew up as an AF brat and the space race big in the household. I was so involved in the story I looked at Tom Wolfe’s list of references and started reading books he read for background. As more and more astronauts and former space race people started writing books I was reading more and more of that time period (I’m still reading them, there are a lot!). At any rate, I finally realized after reading those books that Gus Grissom was a brilliant engineer and test pilot, and a highly respected astronaut— especially by his colleagues. I was livid that Tom Wolfe’s book and the the movie tarnished — nay, smeared— such a highly accomplished, intelligent man who risked everything time and again. I will never forgive Tom Wolfe for that. He should have corrected it (and the NYT; had no idea they wrote a piece. I’ll have to read it and get furious all over again). Please continue to beat the drum on Gus Grissom’s behalf. I do whenever I find someone interested in that time period.

Kathryn, thank you very much for your comment. Yes, shame on Wolfe for slandering Gus Grissom.

Add Comment