Conservatism—social, political and otherwise—used to be the most basic ingredient in the cultural fabric at Texas A&M. Not until 1963 were women and blacks allowed to enroll, which is to say it had long been an all-male, virtually all-White institution. Change did not come easily in College Station as some alumni and administrators resisted with ferocity.

Two freshmen (“Fish,” as they are known at A&M) in September 1964 were Sammy Williams and J.T. Reynolds, both of whom had been educated in Texas’ segregated schools. The former, son of a World War II veteran, had chosen A&M because of its fine engineering department and because it was cheap. He did not play football at Houston Wheatley but ran track and swam. The latter hailed from La Marque Lincoln. He too did not play football, other than the sandlot variety. Wildlife science was his chosen major.

At some point, maybe from the very beginning, Williams and Reynolds were roommates. As was mandatory then, they were members of the Corps of Cadets. They wore military uniforms, marched and bore the abuse of upperclassmen as stoically as possible. Despite his lack of football experience and surely aware that he was taking on a very tough task, Williams went out for the freshman team. Almost as soon as he had donned his uniform, he was confronted by varsity coach Hank Foldberg and told to take it off; Williams never even got out of the locker room. Disheartened, he nonetheless went to track coach Charlie Thomas, showed what he could do as a quarter-miler and was made a member of the team. Soon after that, however, he had academic troubles and was forced to drop out.

A year or so later, Williams was back in Aggieland. He and Reynolds, who had joined an intramural football team, were talking among themselves. They spoke disparagingly about A&M football, then coached by Gene Stallings. These guys were not mistaken in that Aggies football was bad. Ever since Bear Bryant left after the 1957 season to return to his alma mater, the University of Alabama, the Ags had been among the Southwest Conference’s weak sisters. The maroon and white went 1-9 in 1964, 3-7 in 1965 and 4-5-1 in 1966. Had Williams and Reynolds noticed, their school’s team was in fact getting better.

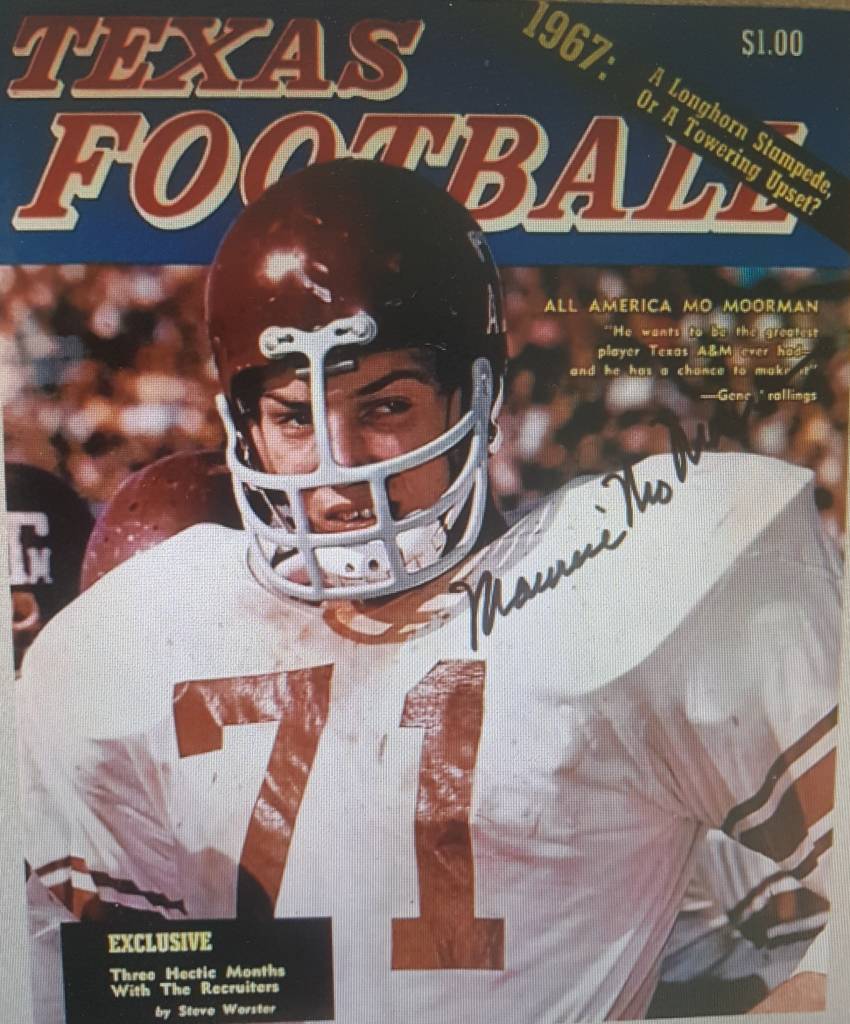

The 1967 Aggies had some fine players, such as Bill Hobbs, Mo Moorman, Edd Hargett, Curley Hallman (later head coach at Southern Mississippi and LSU), Larry Stegent, Wendell Housley, Ross Brupbacher, Bob Long and Tommy Maxwell. (All were White.) They had quite a season, losing their first four and then winning seven in a row including a 20-16 defeat of the Bear’s Crimson Tide in the Cotton Bowl.

No doubt Williams had told Reynolds of his aborted attempt to join the freshman team in 1964. Undeterred, the two met with Stallings. This, I surmise, was in the winter of 1967. He agreed to let them take part in spring drills. They did, and the welcome they got from coaches and players was moderately hostile. Was it easy for walk-ons like Abner Haynes at North Texas State, Darrell Brown at Arkansas, John Westbrook at Baylor or E.A. Curry at Texas? A football practice field is no place for the faint of heart, and we can be sure Williams and Reynolds were tested. They got through spring practice, were allowed to join summer conditioning drills and then—the real deal—fall practice.

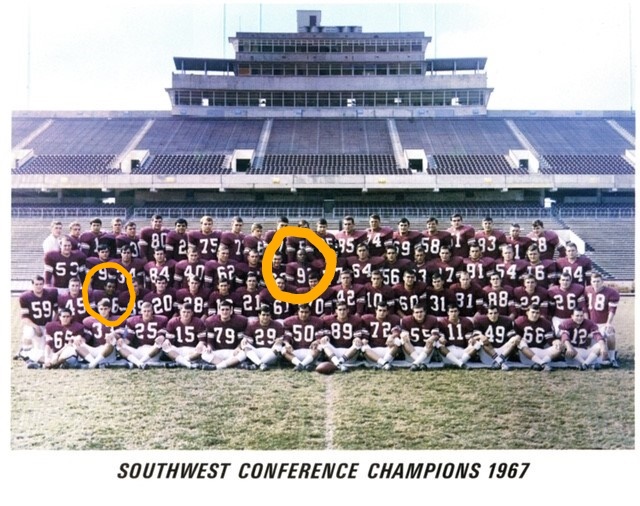

Williams was a receiver, albeit with wooden hands, and Reynolds a linebacker who could play defensive back if necessary. They were among the scrubs, members of the scout team. That is to say, Williams, Reynolds and numerous White teammates served as cannon fodder for Hobbs, Moorman, Hargett et al. It was a grueling three months. Their contribution to the 1967 team’s success was negligible. They were not on the traveling squad, so trips to Tiger Stadium (LSU), Jones Stadium (Texas Tech), Amon G. Carter Stadium (TCU), Razorback Stadium (Arkansas), Rice Stadium (Rice) and the Cotton Bowl against Bryant’s Crimson Tide were out.

Williams and Reynolds, in uniform, took part in pre-game warmups and again at halftime in home games against SMU, Florida State, Baylor and Texas. Otherwise, they stood on the sidelines and watched. So says one account I have read, but another insist that Reynolds saw some action on the kickoff return team. If he did—and how indicative that so little attention was paid—that is significant. These gutsy young men went to Stallings and his assistants more than once to ask why they were not being allowed to contribute. They got stonewalled, with the exception of defensive coordinator William “Dee” Powell, who encouraged them to stick it out. Some of their White teammates did the same and agreed that they deserved to get on the field and play. And if the old-timey right-wingers up in the stands didn’t like it, too bad.

Strangely enough, both got athletic scholarships for 1968 but chose not to play. “We could see the writing on the wall,” said Reynolds. The Ags (freshmen and varsity) were again all-White in 1968 and again mediocre, winners of just eight games that season and in ’69 and ’70. Another black walk-on, Hugh McElroy, a speedy runner/receiver, put on the colors from 1969 to 1971. Mike Bruton and Jerry Honore were Stallings’ first black recruits in 1970.

When Williams and Reynolds graduated in 1969, neither left College Station with fond memories. And yet both had children who later became Aggies and took part in the school’s many traditions. Williams had a long career as a sales engineer for General Electric and other tech companies; Reynolds spent 40 years in the National Park Service.

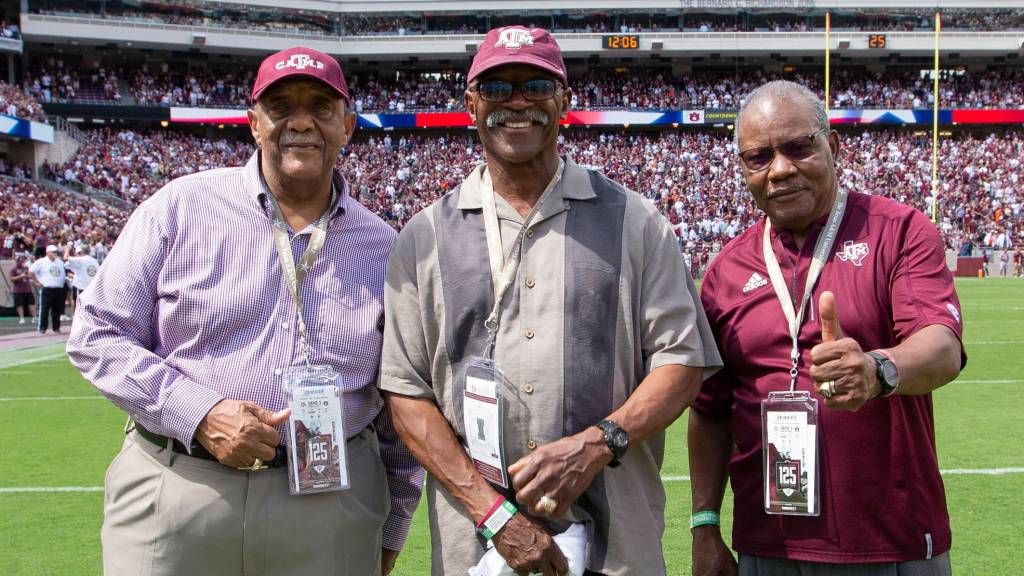

On October 7, 2017, the Aggies hosted Alabama at Kyle Field. This marked the 50-year anniversary of the surprising SWC championship and defeat of the Tide in the Cotton Bowl. Much had changed—dissolution of the SWC, the Ags’ move to the Southeastern Conference, enlargement of the stadium to 100,000-plus seating capacity, and the demographics of the team and student body. There were ceremonies and parties before, during and after the game (a 27-19 Bama victory) to honor the now-aging men who had won the SWC title half a century earlier. Sammy Williams and J.T. Reynolds may have been the most invisible members of Gene Stallings’ 1967 team, but I feel certain they were not ignored that day.

#tamu #collegefootball #racialintegration #texasaggies #genestallings #bearbryant #kylefield #southwestconference #collegestation

Add Comment