Here in the year of our Lord 2022, I doubt you could find anyone with whom I sympathize less than pro basketball and football players. Contemptuous of fans, self-absorbed and prone to violence, they strut and preen, and are lavishly paid, pampered and lionized. Worse, they are all-in on the Only Black Lives Matter thing. The USA was rather different 60-plus years ago, an era from which I will examine two closely related events—one from each sport. They are, I believe, cause for admiration.

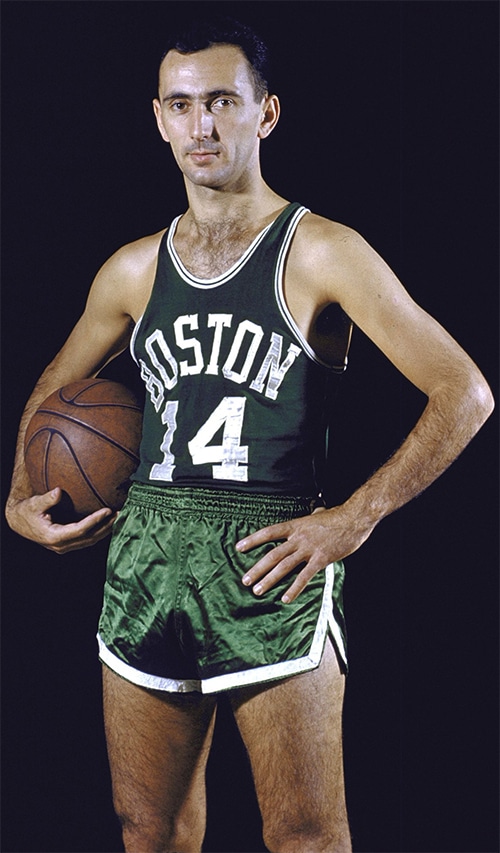

First, the guys in shorts who play indoors with a round ball. The National Basketball Players Association was a fledgling union founded by Boston Celtics guard Bob Cousy in 1954. Back in the stone ages of pro hoops, the players had legitimate grievances—no health insurance, second-class travel, second-class hotels, no per diem and no payment for preseason games. Changes were needed, but NBA commissioner Maurice Podoloff and the owners just stalled and gave their players the brush-off. Promises were made but not kept.

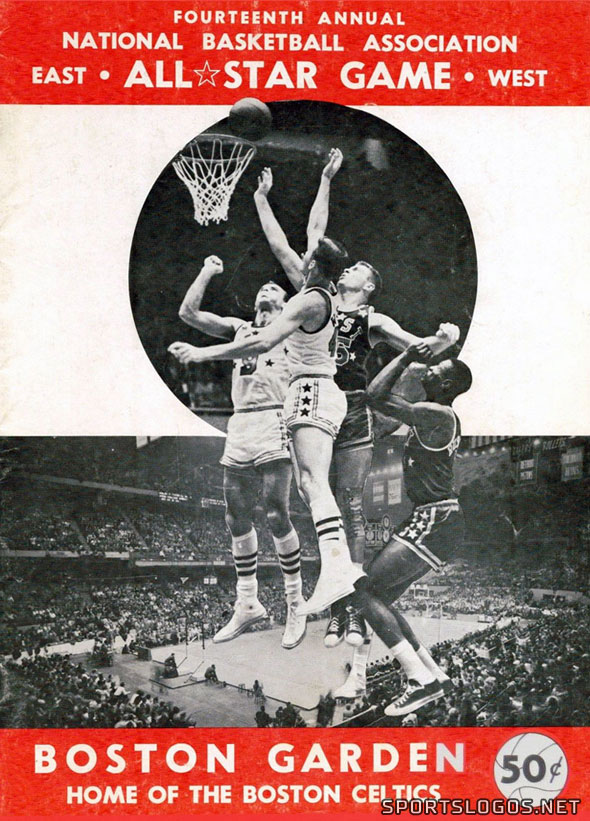

A full decade later, little progress had been made other than in the quality of the play on court. The league’s 14th All-Star Game, scheduled for January 14, 1964, was expected to be a special occasion, regardless of the blizzard howling outside Boston Garden. Celtics owner Walter Brown had invited pro players from the 1920s through the 1950s to attend. More significant, the All-Star Game had never before been televised. If it went well, ABC would likely offer what was then a lucrative broadcasting deal. On that night in Boston, the NBA prepared to step into the limelight.

But the players were in no mood to go along since their union was still not officially recognized, they lacked even a rudimentary pension plan, the minimum salary was $7,500 (many guys had to work summer jobs to make ends meet), and playing conditions left much to be desired. Walter Kennedy, who had succeeded Podoloff as commissioner, and the owners chose not to meet with the NBPA’s designated agent, Larry Fleisher.

Push had come to shove, with the union president, Bob Pettit of the St. Louis Hawks, along with Tom Heinsohn of the Celtics and Oscar Robertson of the Cincinnati Royals demanding action. Absent genuine concessions from the league, they refused to play. ABC’s cameras would be turned elsewhere, and the league would suffer a huge embarrassment. Tipoff, planned for 9 p.m., was looming when the players from both the East and West squads gathered in one locker room. As a Boston policeman guarded the door, they engaged in heated talks. Kennedy entered, made an impassioned plea, then went back to speak to the owners. At one point, Los Angeles Lakers owner Bob Short and Celtics coach Red Auerbach got in and said that they would suffer bad mojo if they did not play. An exasperated Kennedy was soon back with the news they wanted to hear—the owners had essentially caved. Despite not having a signed document, the players called off their wildcat strike. Pettit went out and informed the media that the game would proceed, albeit 15 minutes late. The East won, 111-107, and Robertson (26 points, 14 rebounds and 8 assists) was chosen most valuable player. The NBA became a more professional and prosperous business that night.

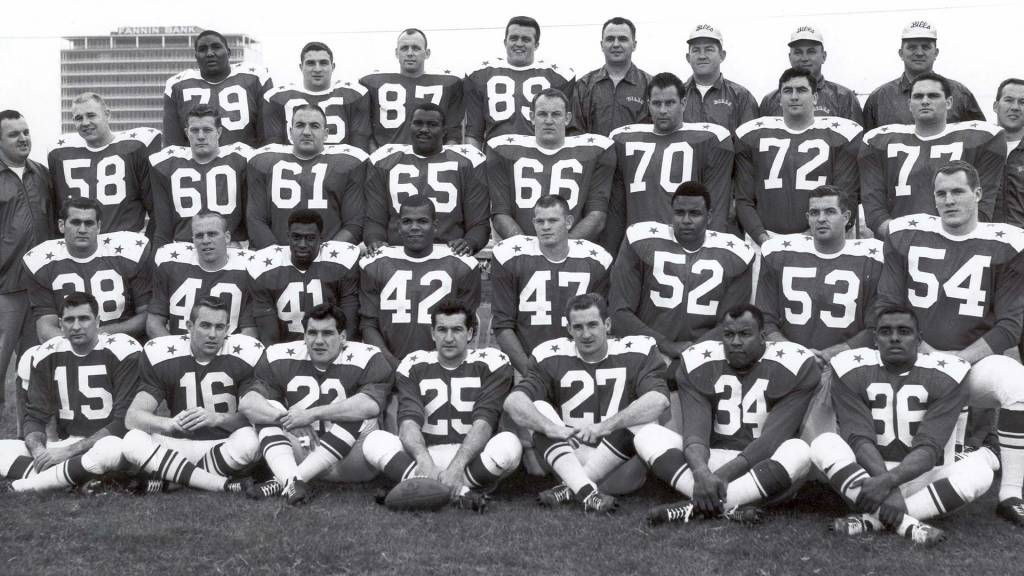

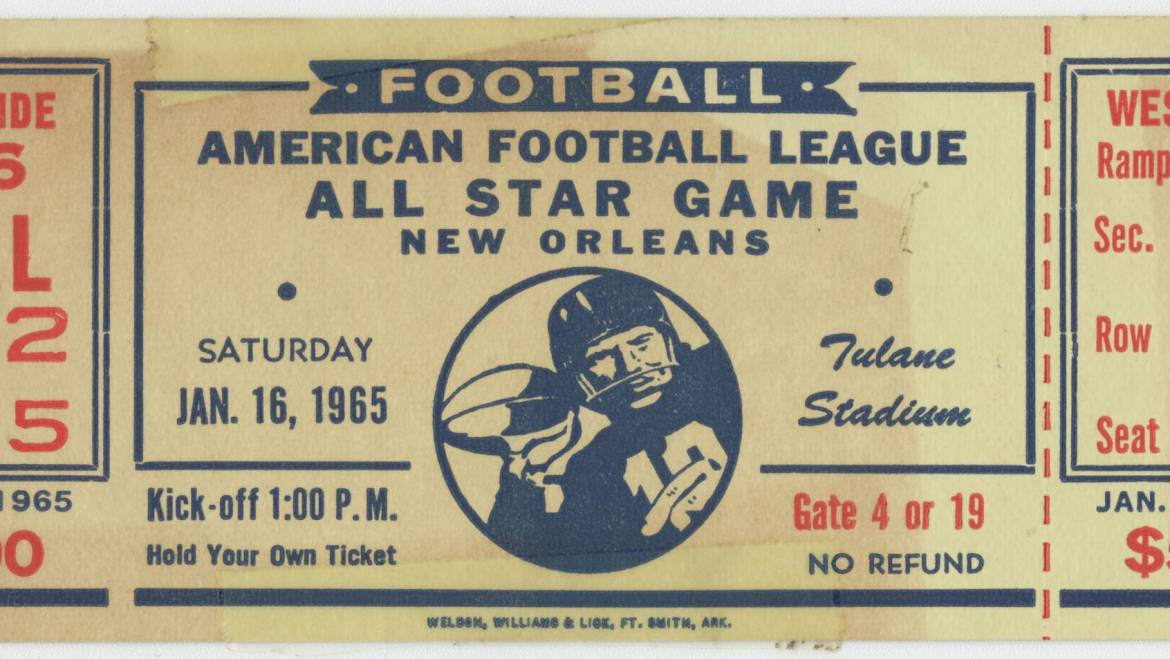

We now turn our attention to the men who wear shoulder pads and helmets, and who play outdoors with a ball in the shape of a prolate spheroid. Almost exactly one year after the big showdown at Boston Garden, the 1964 American Football League season had concluded with the Buffalo Bills being crowned champs. The All-Star Game was to be played, strangely enough, in New Orleans although no AFL team called it home. A local man named Donald Dixon wanted an AFL expansion franchise and promised an enjoyable time to league officials, players, coaches and fans. More than 60,000 people were expected to fill Tulane Stadium for the game.

New Orleans, for all its multicultural flair, was still a Deep South city. While the 1964 Civil Rights Act had taken effect the previous summer, Jim Crow mores lingered. Problems began as soon as the 21 black players (37 were White) got to the airport on January 10. Sorry, they were told, you should take a colored cab. Similar issues arose with hotels, restaurants and nightclubs.

All of the black players gathered in room 990 of the Roosevelt Hotel, which had integrated not long before. Cookie Gilchrist and Ernie Warlick of the Bills, Clem Daniels and Art Powell of the Oakland Raiders, Ernie Ladd and Earl Faison of the San Diego Chargers and Abner Haynes of the Kansas City Chiefs may be called the ringleaders, and they were furious. The issue here was more fundamental than a labor dispute; this was about being treated with dignity. They were not entirely alone, as two White players (Ron Mix of the Chargers and Jack Kemp of the Bills) lined up with them. One may fairly wonder about the views of the 35 other White players—did they care? Were they opposed? They were not, after all, directly affected.

AFL commissioner Joe Foss tried to calm the waters, as did a local NAACP activist, but the players were having none of it. They took a vote, with the numbers 13 in favor and eight against—not unanimous, but good enough. They appointed Warlick, an articulate veteran, to speak to the press about their reasons for having taken that bold stance. New Orleans’ claims of hospitality, he insinuated, were as fraudulent as a Confederate $3 bill. It was by then January 14, and the men were headed out of town with the 1965 All-Star Game in serious jeopardy.

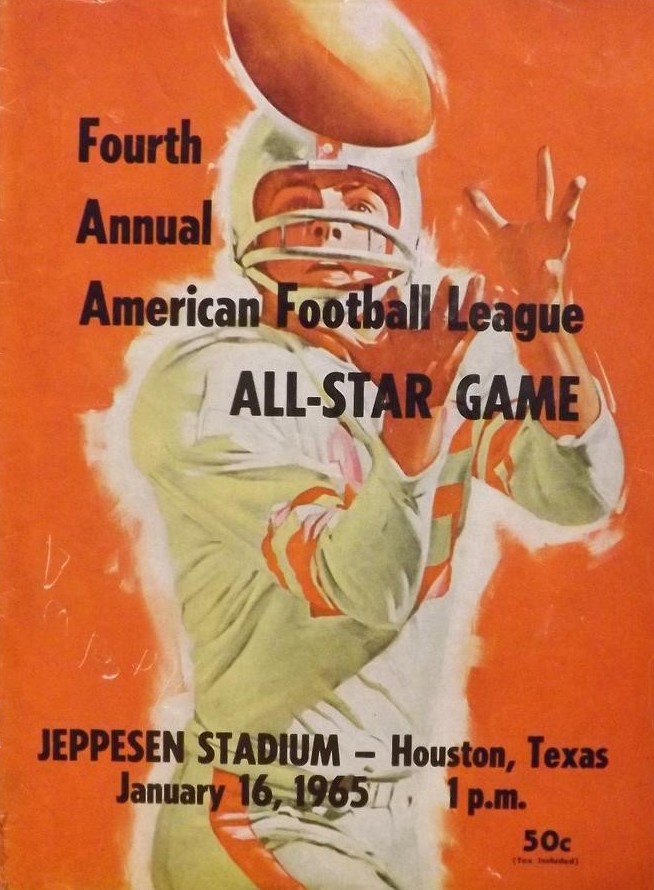

Foss and the AFL owners hid their displeasure but acted quickly. Bud Adams of the Houston Oilers said that Jeppesen Stadium was available, so everybody headed to Houston. An ad hoc All-Star Game was held there, with the West winning, 38-14, before 15,000 desultory fans. Keith Lincoln of the Chargers was named offensive MVP and Willie Brown of the Raiders won defensive MVP honors. It was a new era in Houston, too, as the AFL players stayed at the Shamrock Hilton. They comprised the hotel’s first racially mixed group.

This signal event in the volatile mix of sports and society proved to be a catalyst for change in New Orleans and elsewhere in the South. For one thing, the NFL awarded the city an expansion franchise—the Saints—in 1967. The owner would be the same David Dixon who had brought the AFL to town for a few fateful days in early 1965. NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle had one unusual condition, to which Dixon agreed. Buddy Young, a black player from the 1950s who then worked in the NFL office in New York, was dispatched to New Orleans and had lunch with Dixon at Antoine’s. They were seated at a prominent table and received special service from the head maître’d. The point, made without ambiguity, was that the days of segregation were over.

The only unfortunate aspect of which I am aware took place just four days after the 1965 AFL All-Star Game in Houston. The league’s founder, Kansas City Chiefs owner Lamar Hunt, traded his longtime star running back, Abner Haynes, to the Denver Broncos. He thought Haynes had helped lead the revolt, and what if he had? Hunt, almost universally admired in the world of pro football, should have brought Haynes into his office for a warm, congratulatory meeting. Haynes, who had played a key role in making the league respectable and competitive starting in 1960, never earned more than $28,000. Instead of being sent to the lowly Broncs, he should have gotten a raise.

#nba #afl #abnerhaynes #1964nbaallstargame #1965aflallstargame #oscarrobertson #lamarhunt #bobcousy #bostongarden #neworleans #tulanestadium

2 Comments

as usual Richard excellent reading. I remember the events pretty well my team was the Dallas Texans with Abner Haynes, Lynn Dawson, Chris Buford, e j holub to name a few. we had just won the 63 afl championship in what at the time was the longest game in professional football. no either than Abner Haynes incorrectly gave Houston the football after winning the coin toss to start overtime but the Texans held and won the game on the field goal by former Alabama tight end tommy Brooker. my team left for kc and I have been a cowboy fan ever since through thick and thin. as usual Richard excellent reading and reporting

Billy….oh I remember the Texans at the Cotton Bowl!

Add Comment