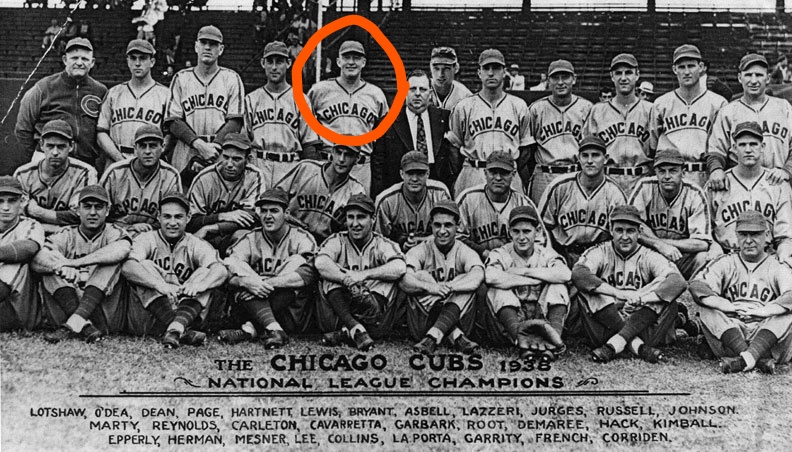

How many modern-day baseball fans could identify Charles Leo “Gabby” Hartnett? Very few. I find this odd since he was quite a player. A Rhode Island native, he was with the Chicago Cubs from 1922 to 1940 and had one final season with the New York Giants; Hartnett also served as the Cubs’ manager from 1938 to 1940. At the time of his retirement, Hartnett was regarded as the finest catcher in National League history. Six times an All-Star, he played in four World Series and had more home runs (236), RBIs (1,179), hits (1,912) doubles (396) and games played (1,990) than any other catcher. National League MVP in 1935, he was an excellent fielder and was among the best at nabbing would-be base stealers. Hartnett was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1955, along with Joe DiMaggio, Ted Lyons and Dazzy Vance.

He was behind the plate during the raucous 1932 World Series when Babe Ruth had his “called-shot” home run, the 1934 All-Star Game when Carl Hubbell whiffed Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmy Foxx, Al Simmons and Joe Cronin in succession (in an era when the strikeout was rare and regarded as an undesirable outcome) and the 1937 All-Star Game when Dizzy Dean’s career-altering injury took place. But those moments pale in comparison to what he did in the last week of the 1938 season.

The Pittsburgh Pirates had been atop the NL standings since the All-Star break, and the Cubs were languishing in fourth place in late August. They narrowed the gap by winning eight straight games (and the Bucs started playing sub-.500 ball), and had fought their way to just 1 ½ back when Pittsburgh came to Wrigley Field for a three-game series. Aiding them considerably during that stretch was Dean, who had been traded from St. Louis to Chicago early in the season. The Cubs won the first game, upping the pressure on Pie Traynor’s team.

It was September 28, 1938. The game had reached the bottom of the ninth, the score was knotted at 5-5, and reliever Mace Brown was on the mound for Pittsburgh. The stadium had no lights—and would not for another half-century—and darkness was starting to fall. The umpires had already indicated that the game would not go into extra innings, and MLB’s rules at the time held that it would be replayed in its entirety the next day if the teams ended up tied.

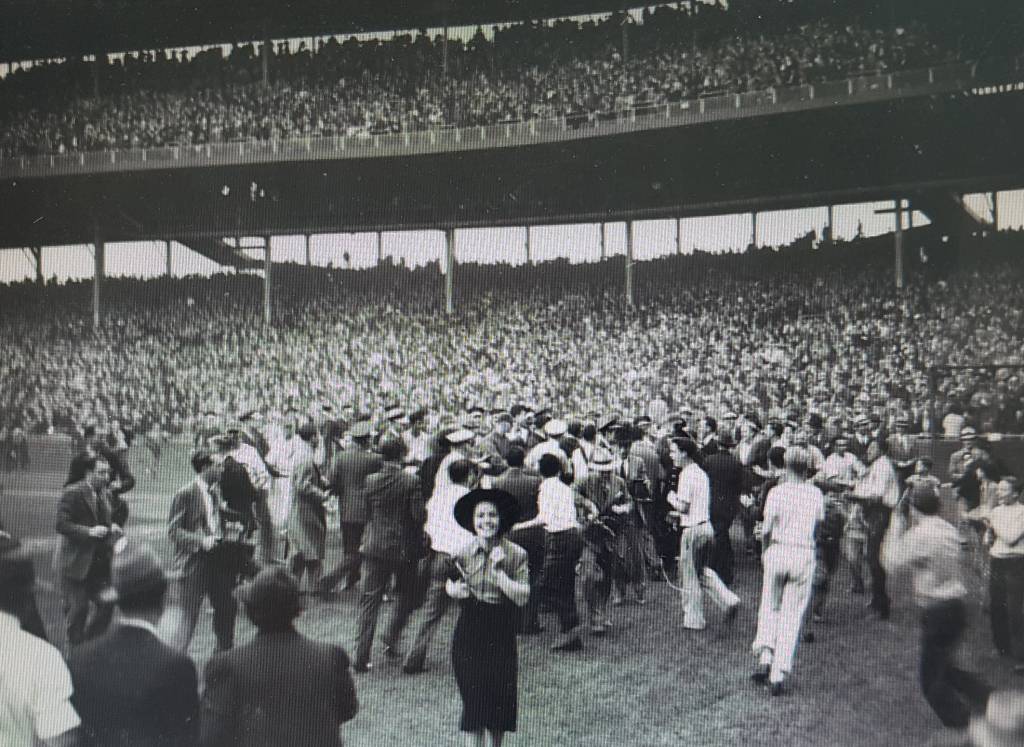

Brown seemed to have the upper hand, working the count to 0-2. At 5:37 p.m., he went into his windup and threw a curve. Hartnett was ready. Undeterred by the gathering dusk, he smacked that thing into the left-center field bleachers. Pandemonium erupted at Wrigley Field as fans rushed out to escort him around the bases. Photos taken that day show a beaming Hartnett engulfed by fans and the police determined to bring him to the safety of the dugout; Brown could later be found in front of his locker, crying like a baby.

Pittsburgh outfielder Paul Waner remembered the Chicago response many years later: “They ran onto the field like a bunch of maniacs, and his teammates and the crowd were mobbing Hartnett, and piling on top of him, and throwing him up in the air, and everything you could think of. I’ve never seen anything like it before or since.”

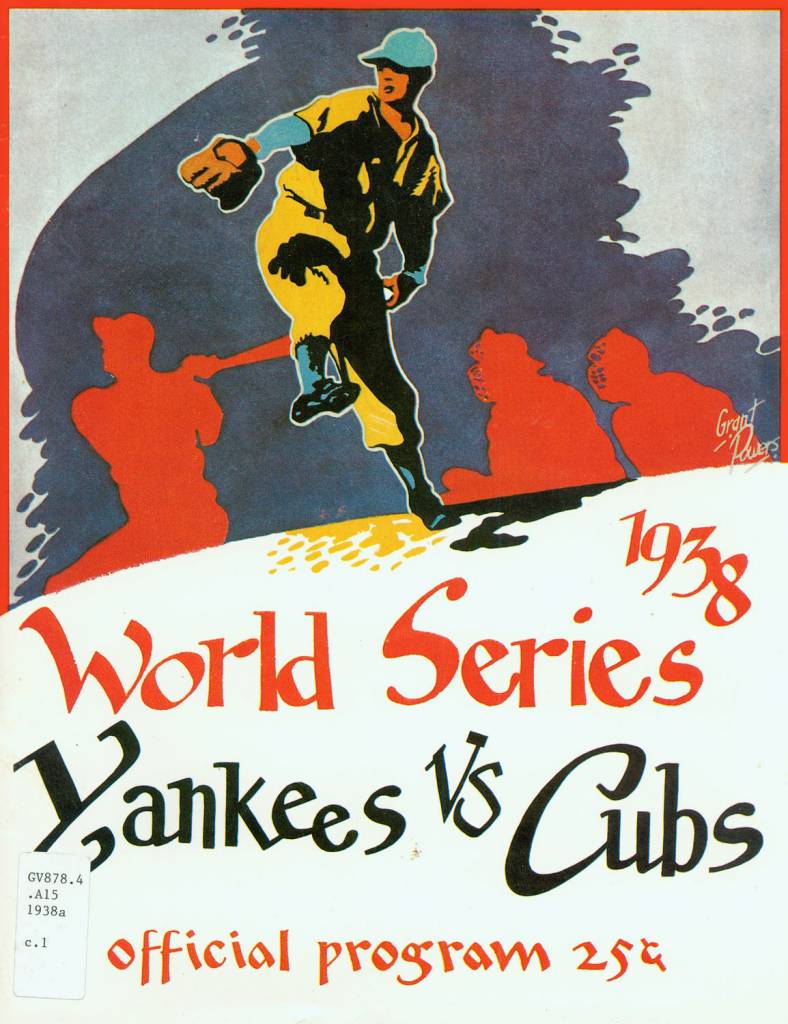

The Cubs’ victory put them in first, they beat the dispirited Pirates again the next day, and soon the National League gonfalon was theirs. It would be nice to say that Chicago defeated the New York Yankees in the 1938 World Series, but no—Gehrig, DiMaggio, Bill Dickey, Red Ruffing et al. swept them in four.

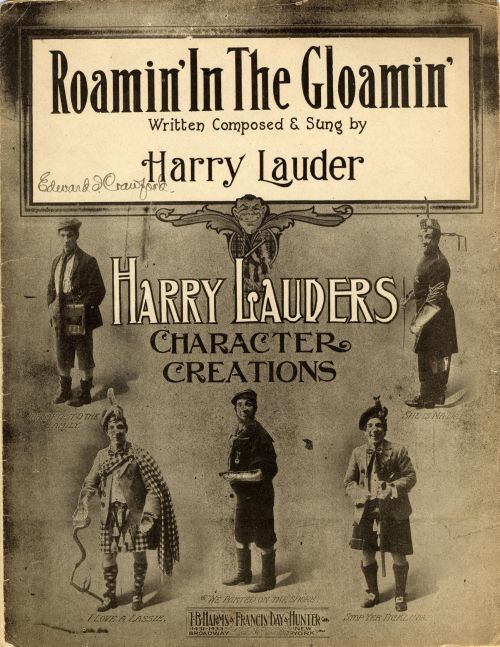

Although Chicago’s win over Pittsburgh had been dramatic, there is another reason it is such a big part of baseball folklore. In the opening paragraph of an Associated Press article, sports writer Earl Hilligan dubbed Hartnett’s dinger “the Homer in the Gloamin’.” (The word “gloaming,” a synonym for “twilight,” comes from the Scots dialect of English in the Middle Ages.) Hilligan’s expression was a play on the title of a 1911 song by Harry Lauder, “Roamin’ in the Gloamin’,” which depicts two Scottish sweethearts courting one evening:

Roamin’ in the gloamin’ on the bonnie banks o’ Clyde.

Roamin’ in the gloamin’ wae my lassie by my side.

When the sun has gone to rest,

That’s the time we love the best.

O, it’s lovely roamin’ in the gloamin’!

#baseballhistory #chicagocubs #gabbyhartnett #homerinthegloamin #pittsburghpirates #1938baseballseason #earlhilligan #dizzydean #wrigleyfield

4 Comments

Wow, he seemed to get more fans than the Beatles! And I have not heard of him. That is not surprising tho.

That is true for most people, Vicki…even hard-core baseball fans.

The end of the 1938 MLB season is full of baseball lore and peculiarities. Mr. Hartnett’s blast was truly hit in the “gloamin'” but only because Daylight Saving Time had ended a mere three days before this 3 p.m. tilt that lasted a tad over 2 1/2 hours. Even though sunset occurred at 5:38, the spatial orientation of Wrigley Field aided in the sensation of darkness because the two-deck ballpark hid the sun 10-15 minutes before the fabled, homeric homer.

Why did the Bucs not give the future HOF catcher an intentional pass? Fading slugger Rip Collins was next and he’d had nothing of the season that his player-manager had forged.

All was for naught as the Yankees swept the Northsiders in a World Series that featured eleven future Cooperstown inductees. Sure, Gehrig, DiMaggio, and Dizzy Dean were on the field but so was Bomber skipper Joe McCarthy and even umpire Cal Hubbard, the only man to make both the MLB and NFL HOF.

Sadly, smart baseball people would later point to Gehrig’s poor performance (no extra base hits) as the first indication that his magnificent body was displaying symptoms of the disease that would kill him several years later.

They had daylight savings time back in ’38??

Add Comment