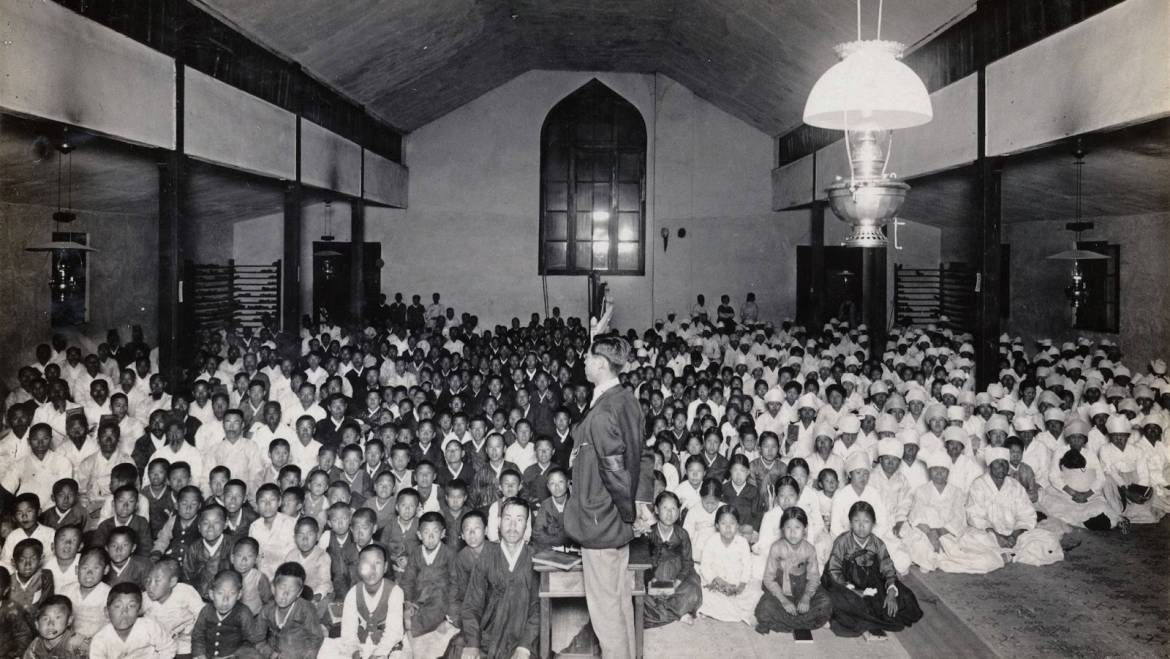

This photo was taken in a Christian church in Pyongyang in the first decade of the 20th century. We do not know the name of the church, nor that of the pastor, who stands at the front with his right hand lifted. Boys and men are to our left, and girls and women to our right. All the illumination is provided by a single lamp suspended from the ceiling. There are no pews, as the congregants sit on the floor.

The seeds of Korean Christianity began to be sown in 1603 when Yi Gwang-jeong brought several theological books written by the Italian Matteo Ricci back from a diplomatic mission to China. It grew slowly and sporadically, aided by French Catholic missionaries. With a message not just of heaven and eternity but of egalitarianism here on earth, it was perceived as a threat by Korean neo-Confucian society and the royal court. The sad and shocking fact is that more than 10,000 Korean Christians were martyred in the 1800s.

slowly and sporadically, aided by French Catholic missionaries. With a message not just of heaven and eternity but of egalitarianism here on earth, it was perceived as a threat by Korean neo-Confucian society and the royal court. The sad and shocking fact is that more than 10,000 Korean Christians were martyred in the 1800s.

Despite seeing so many fellow believers hanged, decapitated and thrown into prison, they persevered. A measure of security did not come until treaties had been signed with Japan, China, the USA and European countries toward the end of the 19th century. By that time, the missionaries were not French Catholics but American Protestants like George Shannon McCune and Samuel Austin Moffett.

In my view, the denominational matter—Catholic or Protestant—is of no special importance, but the American influence on Korean life certainly is. Pyongyang was a Christian stronghold partly because the missionaries brought more than the Gospel; they also brought Western medicine, education and political ideas.

It is unclear to what degree the 1907 Pyongyang Revival resulted from the work of foreigners or indigenous preachers like Gil Seon-ju. Lay Christians traveled as much as 100 miles, some trudging through the snow, to participate. We read of mass conversions, weeping and all-night prayer sessions. Around that time, such institutions as Union Christian Hospital, Union Presbyterian Theological Seminary (now Chongsin University in Seoul) and Union Christian College (Soongsil University) were founded in Pyongyang.

Around that time, such institutions as Union Christian Hospital, Union Presbyterian Theological Seminary (now Chongsin University in Seoul) and Union Christian College (Soongsil University) were founded in Pyongyang.

No doubt, there was tension between the Christians of Pyongyang, and indeed all of Korea, and the Japanese during the colonial era. The imposition of Shinto—in effect, worship of the emperor—was anathema to them. McCune, Moffett and others were expelled from the country in the 1930s for refusing to break the second commandment. In 1942, not long after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the last of the Americans were told to go and the mission schools and churches closed.

We now turn our attention to a man who was born in Pyongyang in 1912, whose grandfather was a Protestant missionary, whose father was a minister, whose mother was a deaconess and who played the organ during church services: Kim Il-sung. He soon disavowed any allegiance to Christianity and embraced communism.

organ during church services: Kim Il-sung. He soon disavowed any allegiance to Christianity and embraced communism.

Kim was chosen by the Russians as their man north of the 38th parallel in 1945 when Pyongyang had 300,000 residents, of whom one-sixth were church-going Christians. That changed quickly. The crosses that had dotted the skyline of “the Jerusalem of the East” came down as Kim installed his own version of communism, with him at the epicenter. The first statue of Kim Il-sung was unveiled on Christmas day, 1949.

Christians who resisted were killed or sent to the gulag and given “special” treatment. Most, in time, came to accept the new reality—genuflecting and keeping a well-polished photo of Kim in their homes. The Kim personality cult was boosted by Han Sor-ya. An ardent communist, he first called Kim “our sun” and came up with other honorifics. Han’s 1951 novella entitled Jackals referred often to Americans, and the key figure was a villainous American missionary. Even today, the term “jackal” is synonymous with “American” up north.

This is somewhat understandable in light of the damage U.S. bombers did to Pyongyang during the Korean War. The few remaining churches were turned into schools or hospitals.

Decades of totalitarian rule went by, and all outward expression of faith was ruthlessly banned. But if the  stories of North Korean defectors can be believed, Christianity in Pyongyang and other cities survives in an underground setting. As to their numbers, estimates are as low as 10,000 and as high as 300,000.

stories of North Korean defectors can be believed, Christianity in Pyongyang and other cities survives in an underground setting. As to their numbers, estimates are as low as 10,000 and as high as 300,000.

Since the late 1980s, a series of “show churches” have been built with funds provided entirely by South Korean and American Christians. There are five in Pyongyang, although Jesus’ name is rarely mentioned in sermons. They are instead about morale, patriotism and the wise and benevolent three-generational leadership of the Kims.

An organization called Open Doors annually ranks countries noted for repression of Christianity. Things are bad in places like Afghanistan, Somalia, Sudan and Pakistan, but in 2020, for the 20th consecutive year, the DPRK came out on top—or should I say bottom.

2 Comments

Richard:

A great article with outstanding content and research. It is a sad story of the Korean Christians as well as the influence of Communism. I thought the photos you included really help illustrate the article. Great work!

Rex

Thank you, Rex. I agree, this is just a heartbreaking story. I suppose that some Devil-minded people would say he was behind it.

Add Comment