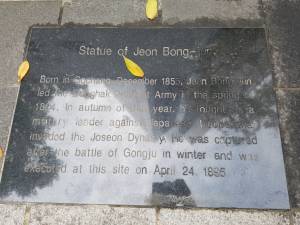

Although I admire King Sejong, Admiral Yi Sun-shin, Park Chung-hee, Kim Yuna and all seven members of BTS, I admire Jeon Bong-jun even more. For that reason, on consecutive days I journeyed to the intersection of Jong-ro and Ujeongguk-ro in downtown Seoul. Just across the street from the Bosingak Bell stands a 1.4-meter statue of the Donghak Peasant Revolution leader.

I do not think it is unfair to compare him to Spartacus, the first-century BC gladiator who led a major slave uprising against the Roman Republic. Of low birth, he proved himself a fierce and effective warrior, one who inspired his legions in an effort to gain their freedom. Unlike Jeon, however, Spartacus died on the battlefield.

Is there a subject about which Korean historians are more sensitive than slavery? It existed here for more than 2,000 years—even before the Three Kingdoms period. Dr. Mark Peterson of Brigham Young University contends that Korea has a longer unbroken chain of slavery than any other country. The Silla dynasty’s “bone-rank” system, while extremely rigid, did allow some social movement but only downward; nobody could move up, especially those toward the bottom.

Early in the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties, proclamations of freedom for slaves were made and yet soon things were back as before with royals and yangban lording it over the cheonmin (vulgar commoners), the baekjeong (untouchables), the ssangnom (those of low caste without genealogy) and nobi (actual slaves). These pitiful groups were severely limited in where they could live and the most degrading kind of work was reserved for them. They could be bought, sold, given away and, of course, mistreated at the whim of their “superiors” in Korea’s feudalistic society.

But when the Mongols invaded in the 13th century, when Toyotomi Hideyoshi brought his soldiers over from Japan in 1592 and when the Manchus came a-calling in 1636, Korea’s rulers asked these people for help. They fought and died in defending their country.

The slaves (or “serfs” as some Korean historians prefer to call them) occasionally rebelled. It happened at least twice in the turbulent 19th century, with the Gwanseo Peasant War of 1811-12 and the Imsul Peasant Revolt of 1862. In both cases, low-caste Koreans took up arms—actually just spears and clubs—and demanded a degree of justice. These uprisings were localized and short-lived, and never was the dynastic system seriously challenged.

The oppressed Koreans may not have been too literate, but they undoubtedly employed oral history. Stories of what their ancestors had done in a vain effort to bring about social change were told and sometimes embellished. Jeon Bong-jun, the subject of this article, was born in what is now Jeong-eup in Jeollanam Province in 1854. The Donghak Peasant Revolution started in January 1894 when the  magistrate of Gobu instituted some new taxes and forced local peasants to build a reservoir. Although there is no way of knowing for certain, I surmise that Jeon, Kim Gaenam, Son Hwajung, Choe Gyeongseon and others said something to the effect of “here we go again.”

magistrate of Gobu instituted some new taxes and forced local peasants to build a reservoir. Although there is no way of knowing for certain, I surmise that Jeon, Kim Gaenam, Son Hwajung, Choe Gyeongseon and others said something to the effect of “here we go again.”

The centuries of mistreatment, abuse and suffering weighed on these men. Adherents of the Donghak religion/philosophy created by Choe Je-u (born, interestingly enough, into an aristocratic family), they rebelled. The Joseon military could not put it down, and soon the Chinese and Japanese were fighting in a confusing three-way war. Jeon rose to the top of the rag-tag army, winning some rather impressive victories at Jeonju Fortress and Hwangto Pass. Inevitably, however, they fell to the bigger numbers and better weaponry of government forces.

In December 1894, after the Battle of Ugeumchi Jeon was betrayed by one of his underlings and captured by Japanese soldiers. Beaten with heavy sticks and with both of his legs broken, he was put on a wooden pallet and carried all the way to Seoul. A famous photo shows him, topknot on his head, glaring defiantly at the camera.

Jeon, the “Mung Bean general,” knew what awaited him in the capital. At 2 a.m. on April 24, 1895, he was hanged at the very spot where his statue now stands. The Donghak Peasant Revolution was by no means a failure, as some of its demands were met in the Gabo Reforms. But it had frightened the pants off a lot of Korea’s upper-echelon citizens. They must have known—much as White Southerners in the  USA during the Jim Crow era knew—that change had to come. One of Donghak’s most basic tenets was the equality of all persons. Jeon raged against the two-millennia-old division of rulers and ruled, wherein any attempt to alter the status quo was “a sin against heaven” and a civil crime.

USA during the Jim Crow era knew—that change had to come. One of Donghak’s most basic tenets was the equality of all persons. Jeon raged against the two-millennia-old division of rulers and ruled, wherein any attempt to alter the status quo was “a sin against heaven” and a civil crime.

The Gabo Reforms supposedly put all Koreans on an equal basis, but writing something on paper is not the same as changing attitudes and behavior. Some of this country’s social observers say equality was not achieved until around 1930, during the Japanese colonial era. Others say that only the advent of the Korean War 20 years later brought it about. And a few insist that traces of the old ways still linger. When I see pyeji jumneun saram (“trash pickup men”) on the streets of Seoul, I wonder about their ancestors.

Add Comment