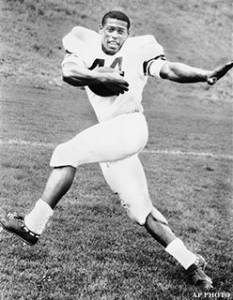

The recent death of Floyd Little—an all-America running back at Syracuse and then a star for nine years with the Denver Broncos—has sparked a series of obituaries and retrospectives. Number 44 deserves it because he really could play. Versatile, fast and strong despite standing just 5′ 10″ and weighing 195 pounds, he was a gamer.

because he really could play. Versatile, fast and strong despite standing just 5′ 10″ and weighing 195 pounds, he was a gamer.

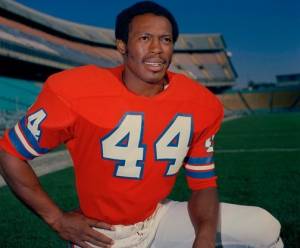

Little’s 1983 induction into the College Football Hall of Fame was just about a certainty, but his situation with the pros was different. Although the Broncos never reached the playoffs during his career (1967 to 1975), you must remember how awful they had been in the seasons before that. Little’s dynamic play made them at least respectable. Still, his numbers are not overwhelming: He averaged  just 3.9 yards per carry and 54 yards per game, and only once (1971) did he exceed 1,000 yards rushing. I concede that his 54 touchdowns look good, and Little was an excellent receiver out of the backfield, and also returned punts and kickoffs. He was a very good player, but the consensus seemed to be that he did not qualify as a “great” one, and the Pro Football Hall of Fame is supposed to be reserved for only the best. Little’s credentials were borderline. More than 30 years passed and Little, who had earned a master’s degree during his off-seasons, was running a couple of car dealerships on the West Coast. Not in the Hall? He had never even been nominated! Then a highly unusual thing happened in 2003. He met Tom Mackie.

just 3.9 yards per carry and 54 yards per game, and only once (1971) did he exceed 1,000 yards rushing. I concede that his 54 touchdowns look good, and Little was an excellent receiver out of the backfield, and also returned punts and kickoffs. He was a very good player, but the consensus seemed to be that he did not qualify as a “great” one, and the Pro Football Hall of Fame is supposed to be reserved for only the best. Little’s credentials were borderline. More than 30 years passed and Little, who had earned a master’s degree during his off-seasons, was running a couple of car dealerships on the West Coast. Not in the Hall? He had never even been nominated! Then a highly unusual thing happened in 2003. He met Tom Mackie.

This Delaware native was just over the moon for Floyd Little. A fan since age 10, he began an enthusiastic campaign to get the attention of the media and more important, the PFHoF voters. Mackie created DVD’s and PowerPoint presentations that were fairly persuasive, as was his fervor. He bombarded anyone who would listen with items such as “44 reasons to elect Floyd Little to the Pro  Football Hall of Fame” and “44 Hall of Famers who like Floyd Little.” Six years of non-stop guerilla marketing brought a nomination in 2009 and induction in 2010. When Little put on that gold blazer and spoke in Canton, Ohio, he made sure to thank Mackie. He had gone to war for the New Haven native and earned a surprising victory.

Football Hall of Fame” and “44 Hall of Famers who like Floyd Little.” Six years of non-stop guerilla marketing brought a nomination in 2009 and induction in 2010. When Little put on that gold blazer and spoke in Canton, Ohio, he made sure to thank Mackie. He had gone to war for the New Haven native and earned a surprising victory.

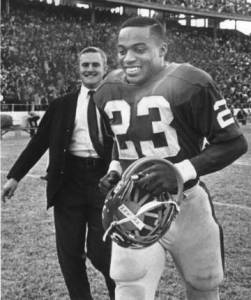

Little and Mackie certainly share a deep bond. But this was just football. Football—or any other sport—alone could not compel me take action. To argue that guy A is better than guy B or guy C, no matter how empirically based, is a boring and fruitless endeavor. Something more is needed, and that explains my own Mackie-type advocacy of Abner Haynes and Jerry LeVias. I championed them not only because they played ball well (Haynes at North Texas State, then the Dallas Texans, Kansas City Chiefs, Denver Broncos, Miami Dolphins and New York Jets, and LeVias at SMU and then the Houston Oilers and San Diego  Chargers), but for their role in integrating the college game in Texas and throughout the South. Again and again, I made the point that they endured much of what Jackie Robinson did with the Brooklyn Dodgers in the late 1940s. Like Robinson, they prevailed despite enormous opposition. This transcends football.

Chargers), but for their role in integrating the college game in Texas and throughout the South. Again and again, I made the point that they endured much of what Jackie Robinson did with the Brooklyn Dodgers in the late 1940s. Like Robinson, they prevailed despite enormous opposition. This transcends football.

Inspired by Haynes, I wrote about 10 articles in which I assessed his showing with the NTSU Eagles between 1957 and 1959, how he was more deserving of the ’59 Heisman Trophy than the winner, LSU’s Billy Cannon, and how he got the integration ball rolling and paved the way for LeVias nine years later. For much of 2016, the College Football Hall of Fame was flooded with letters from me (on “Abner Haynes for the College Football Hall of Fame” stationery) in which I extolled Haynes the player and Haynes the pioneer. It was all to no avail, as the CFHoF refused to budge. Haynes, you see, had not been a first-team all-American, and he was at a no-name school like North Texas. I patiently informed Steve Hatchell and his colleagues at the Hall that racism explained both of those matters.

My involvement with LeVias began much earlier, when I was writing Breaking the Ice / Racial Integration of Southwest Conference Football. That book, which came out in 1987, detailed how the Rice Owls, TCU Horned Frogs, Arkansas Razorbacks, SMU Mustangs, Texas A&M Aggies, Texas Tech Red Raiders, Baylor Bears, Texas Longhorns and Houston Cougars finally integrated after years of Jim Crow football and the gentleman’s agreement. LeVias, recruited by Hayden Fry of SMU, was the key figure. He and I have stayed in touch all these years.

Raiders, Baylor Bears, Texas Longhorns and Houston Cougars finally integrated after years of Jim Crow football and the gentleman’s agreement. LeVias, recruited by Hayden Fry of SMU, was the key figure. He and I have stayed in touch all these years.

(Haynes and LeVias overlap in one sense. When the latter was making history with the Ponies between 1966 and 1968, he sometimes met with Haynes who had gone through similar turmoil a decade earlier.)

Besides writing Breaking the Ice, I pushed the Texas Sports Hall of Fame to let LeVias in. How in the world could those fine people in Waco keep him out of their Hall? Year after year went by, and you can rest assured they heard from me. When LeVias was inducted in 1995, I was there. He mentioned me thrice in his acceptance speech, and when he did I nearly wept.

It was more of the same with the College Football Hall of Fame. LeVias’ athletic achievements were made plain—repeatedly—as well as the significance of his integrating the SWC and by extension the Southeastern Conference and the Atlantic Coast Conference. I wore them down, and LeVias got his due at New York’s Waldorf Astoria Hotel in 2003, along with Roger Wehrli of Missouri, Ricky Bell of USC,  Ron Pritchard of Arizona State, Murry Bowden of Dartmouth, Tom Brown of Minnesota, Barry Sanders of Oklahoma State, Jimbo Covert of Pittsburgh, Joe Theismann of Notre Dame, Billy Neighbors of Alabama, John Rauch of Georgia, and coaches Doug Dickey (Tennessee and Florida) and Hayden Fry (SMU, North Texas and Iowa). I was in attendance that night.

Ron Pritchard of Arizona State, Murry Bowden of Dartmouth, Tom Brown of Minnesota, Barry Sanders of Oklahoma State, Jimbo Covert of Pittsburgh, Joe Theismann of Notre Dame, Billy Neighbors of Alabama, John Rauch of Georgia, and coaches Doug Dickey (Tennessee and Florida) and Hayden Fry (SMU, North Texas and Iowa). I was in attendance that night.

Pardon the redundancy, but I must state that Wehrli, Bell, Pritchard et al. were merely football players and coaches. Little, too, was just a football player. Haynes and LeVias were more, and that is why I worked on their behalf. What Mackie did for the Broncos’ RB was nice, it was admirable, and it was successful. I applaud both of them, but I would not have lifted a finger in that regard.

Add Comment