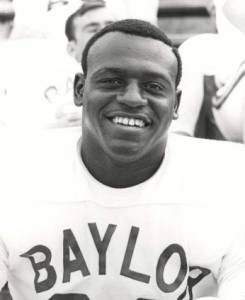

In the spring of 1983, I started working on my first book. It pertained to racial integration of Southwest Conference football. I was deeply disappointed when I learned that John Westbrook had died. What guts it must have taken to walk onto the Baylor football team 18 years earlier! A running back, he endured four years of mistreatment (with some exceptions) by White coaches, teammates, teachers, students and fans, not to mention having at least a few black people accuse him of being a sellout and/or traitor.

I regret not having the chance to interview John Westbrook, although I twice spoke with his widow, Paulette. Perhaps it was she who directed me  to a distant relative of his in Elgin, Texas by the name of Harvey Westbrook. During my research for said book and on several other occasions, we met at his home or the City Café on Main Street. Westbrook was born in 1922, exactly 30 years before me.

to a distant relative of his in Elgin, Texas by the name of Harvey Westbrook. During my research for said book and on several other occasions, we met at his home or the City Café on Main Street. Westbrook was born in 1922, exactly 30 years before me.

Harvey Westbrook had quite a life story himself. Of course, he went through the segregated educational system that once seemed natural and permanent in all the southern states. He graduated from Elgin’s Booker T. Washington High School, just as John Westbrook did in 1965 before heading off to Waco. He saw heavy fighting in the European theater of World War II, came home and got a degree from Prairie View A&M (then the top college for blacks in Texas). He took graduate courses at the University of Nebraska and the University of Iowa, finally getting a master’s degree in agricultural education from Tuskegee Institute. (It was because of Westbrook that I became, for a short time, the only White member of the Elgin chapter of the NAACP.)

Tuskegee is the industrial school in Alabama run by Booker T. Washington—namesake of both Westbrooks’ alma mater in Elgin—between 1881 and 1915. The Civil War was over, and so was Reconstruction. The south had been “redeemed,” and the White folks, many of them ex-Confederates—were back in charge. The foundation of Tuskegee in the heart of Dixie was risky business since education for freed slaves and their sons and daughters constituted something of a challenge to the racial hierarchy. Washington always emphasized industry (farming, bricklaying, etc.) over pure academics. He cultivated northern philanthropists like such as Andrew Carnegie, Collis P. Huntington, John D. Rockefeller, Henry H. Rogers and George Eastman, and really played his role as a supplicant. Nobody has been smeared with the “Uncle Tom” epithet more than Washington who, it must be said, had his people’s immediate and long-term survival in mind. Constantly walking a tightrope, he built this school against all odds. If Tuskegee, which did not achieve university status until 1985, has never rivaled Howard or Morehouse or Fisk, it surely served a valuable purpose.

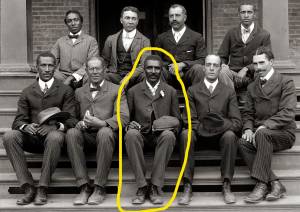

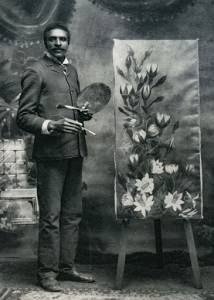

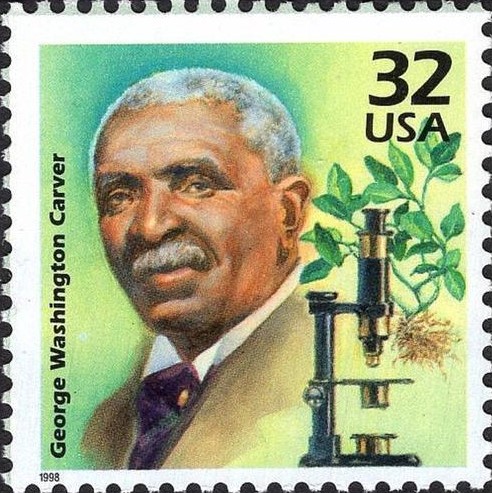

In 1896, Washington made by far his most important recruiting pitch. He convinced George Washington Carver to leave Iowa State University and come join him in Alabama. Like Washington, Carver had been born in slavery. A native of a little town in southwestern Missouri, he scratched his way to an education—first as an over-age student at a high school in rural Kansas, then at Simpson College and  Iowa State. You can imagine the social problems he faced as the first black student at both of those institutions. He switched his major from music (he played many instruments) and art (he was an excellent painter) to botany, proving himself academically. In his spare time, Carver served as a masseur for the ISU football team. Was he competent? Well, his work in plant pathology and mycology drew national attention. Carver’s teachers and fellow students adored him, so he remained in Ames to get a master’s degree. He was on the faculty when Washington came calling.

Iowa State. You can imagine the social problems he faced as the first black student at both of those institutions. He switched his major from music (he played many instruments) and art (he was an excellent painter) to botany, proving himself academically. In his spare time, Carver served as a masseur for the ISU football team. Was he competent? Well, his work in plant pathology and mycology drew national attention. Carver’s teachers and fellow students adored him, so he remained in Ames to get a master’s degree. He was on the faculty when Washington came calling.

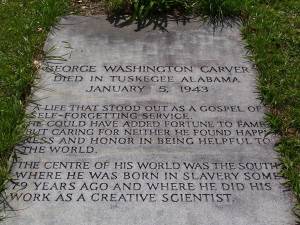

Two professors at Iowa State, Joseph Budd and Louis Pammel, urged him to stay. “George,” they basically told him, “you can earn a Ph.D. here, teach and do research in a first-class academic setting.” Who knows what this brilliant man, this enigmatic genius, might have done, and what inventions and discoveries might have resulted if he had taken the well-intended advice of Budd and Pammel? But the charismatic Washington sold Carver on his vision of what Tuskegee could mean to the downtrodden black people of the South. He made the fateful decision to go, and that school would be his home for the last 47 years of his life.

had taken the well-intended advice of Budd and Pammel? But the charismatic Washington sold Carver on his vision of what Tuskegee could mean to the downtrodden black people of the South. He made the fateful decision to go, and that school would be his home for the last 47 years of his life.

Despite a steady stream of donations from rich Yankees, Tuskegee was perpetually short of money for buildings, equipment, teachers’ salaries and scholarships. Carver, easily the most distinguished member of the school’s faculty, had a small apartment in one or another of the male dormitories on campus. I will not try to list his many scientific achievements, but the most renowned may have involved teaching students  and local farmers how to grow peanuts, sweet potatoes and soybeans—not only for sale on the market but to feed their own families. Until he came along, they planted just cotton, cotton and more cotton. That, he proved, led to depleted soil. He helped pull countless sharecroppers, both black and White, out of poverty.

and local farmers how to grow peanuts, sweet potatoes and soybeans—not only for sale on the market but to feed their own families. Until he came along, they planted just cotton, cotton and more cotton. That, he proved, led to depleted soil. He helped pull countless sharecroppers, both black and White, out of poverty.

Harvey Westbrook graduated from Tuskegee in 1955, more than 10 years after Carver’s death, so they would not have met. But he often talked to me about the great Carver, whom Time magazine called “a black Leonardo da Vinci” in 1941. He was admired by such men as Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, Mahatma Gandhi and Franklin D. Roosevelt, and for good reason. Even so, Carver could have done more if he had been provided with a decent lab, assistants, stenographers and basic support from the Tuskegee administration. He used one microscope for nearly three decades, something I find quite sad. Modest to a fault, he once privately joked that he was a mere “cook stove scientist.” While I hold Washington in high esteem, I have to note that he tended to be jealous of Carver, belittling him and often hindering his work. He offered his resignation numerous times, but Washington never accepted it. The next two principals, Robert Moton and Frederick Patterson, showed him more respect and gave him a tiny bump in salary. Carver cared little about money, making loans or outright gifts to students, struggling farmers and just about whoever knocked on his door.

note that he tended to be jealous of Carver, belittling him and often hindering his work. He offered his resignation numerous times, but Washington never accepted it. The next two principals, Robert Moton and Frederick Patterson, showed him more respect and gave him a tiny bump in salary. Carver cared little about money, making loans or outright gifts to students, struggling farmers and just about whoever knocked on his door.

Carver’s long professional life served to disabuse White people of their racial stereotypes. He was living proof that blacks were not short on intellectual firepower; Carver could run circles around most of the Whites in the educational and scientific realms of the day. And—need it be said?—his brilliance and work ethic overcame 1,001 Jim Crow obstacles. Although he has been honored in numerous ways, what he did to advance black civil rights is still not fully appreciated.

4 Comments

Good story about these three gentlemen but what a great decision for George Washington Carver. He may not able to earned a Ph. D degree but what he did to these farmers, educate and took their lives out of poverty is unbearable. Thanks for this Rich!

Well, thanks for reading it, Andrea. Yes, all three are worthy of our respect. I only got to meet Harvey W. As for Carver, he was a scientific genius but even more he had a soul as deep as a river.

Fascinating men. Their individual contributions to society were against all odds, and are so commendable. If I were to expand my viewpoint to that of the entire world both present and past, I still see people groups who are oppressed all over the world, who also are still having to overcome the thoughts of disappointment, failure and oppression. In the midst of these irrational, unkind, evil, racial wars, there are still hearts in people who want to be overcomers even with the absence of our freedoms and liberties. I want it for them too! The imbalance of justice and fairness which are due to men of hatred who are in powerful positions, whether as bullies , neighbors, teachers, coaches, administrators or dictators must end. We all must call out those who hate, encourage all those who are being hated and afflicted, to stay the course, to be encouraged by victories of Carver et al. For in the end, the individuals, groups, societies and regimes that abuse and punish other races, other religions, etc. can never stand and will not last. Justice, truth and love for our fellow man will prevail.

Here is a sad fact I did not manage to squeeze into the story: Carver was a castrato. His owner, Moses Carver, was “good” to him in most ways. But he apparently feared that Carver would grow up and attempt to seduce his White daughter. So he had the boy’s testicles chopped off. This explains Carver’s unnaturally high voice, and it was confirmed upon his autopsy in 1943. I have heard a recording of his speaking, and he sounds female.

Add Comment