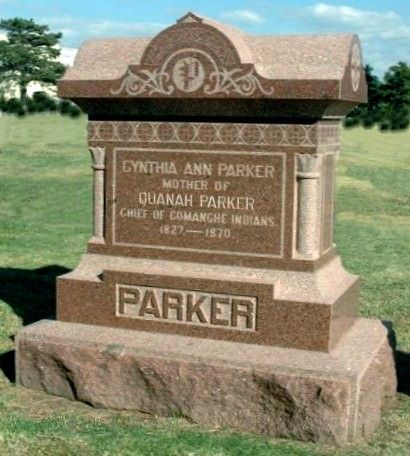

Stockholm syndrome is a loosely defined psychological condition in which hostages, against all logic, develop an alliance with their captors. Despite having been taken, sometimes violently, they develop an emotional bond and choose to remain rather than leave when given the opportunity. The most famous modern-day victim of Stockholm syndrome may be Patricia Hearst, the newspaper heiress snatched in February 1974 by the Symbionese Liberation Army, a self-styled “urban guerrilla group.” She took a new name (“Tania”), denounced her rich family, advocated revolution and helped rob a bank before being arrested and put on trial. Within a few weeks, Hearst had stopped spouting radical lingo and claimed to have been brainwashed during those stressful times. Her conviction for criminal activities as an SLA member was forgiven by Presidents Carter and Clinton. Another such hostage−apostate was Cynthia Ann Parker (1827−1870). Hers was a strange and epic tale, loaded with mournful romance and pathos due to ties of consanguinity between abductors and abductees, scalpers and scalpees, murderers and murderees.

Before going any further, I am obliged to state that American Indians (Native Americans, if you prefer) had begun to retreat almost as soon as the first European settlers arrived in Jamestown, Virginia and Plymouth, Massachusetts. The Allegheny Mountains were no barrier, merely slowing them down. Violence, decimation from new diseases, a severe reduction in the number of buffaloes available for hunting and broken promises had been the Indians’ lot, so their anger was understandable. That is half of the background for the tragic incidents that followed.

Violence, decimation from new diseases, a severe reduction in the number of buffaloes available for hunting and broken promises had been the Indians’ lot, so their anger was understandable. That is half of the background for the tragic incidents that followed.

The other half pertains to the Parker clan. Its patriarch was John Parker, a Predestinarian Baptist preacher, veteran of the American War of Independence and original member of the Texas Rangers. Parker had come from Virginia, where several family members were killed by Indians, and he responded with utmost vigor. He led his family from there to Georgia to Tennessee, to southern Illinois, to Arkansas and finally to Texas. In 1834, empresario Stephen F. Austin offered him 4,428 acres of choice land at the headwaters of the Navasota River. The fact that it was on the edge of the frontier and thus vulnerable to Indian attack did not seem to bother Parker. Among the 34 family members and friends who became “Texians” (residents of Mexican Texas and later the Republic of Texas) was his granddaughter Cynthia Ann.

Parker, his son James and other men quickly started to construct Fort Parker, a crude wooden establishment enclosing four acres. Although a treaty had been negotiated with some local tribes, that did not guarantee security from the Comanches, lords of the southern Great Plains. They could raid with startling speed and savagery, and just such a calamity befell Fort Parker at dawn on May 19, 1836—less than a month after the Battle of San Jacinto and Texas independence. Some were able to escape, some were badly mauled but survived, five were killed, and five were taken prisoner: Cynthia Ann (9); her brother John Richard (6); her aunt Elizabeth Kellogg (40); her cousin Rachel Plummer (17); and her nephew James Pratt Plummer (2). To be clear, James was Rachel’s son.

were able to escape, some were badly mauled but survived, five were killed, and five were taken prisoner: Cynthia Ann (9); her brother John Richard (6); her aunt Elizabeth Kellogg (40); her cousin Rachel Plummer (17); and her nephew James Pratt Plummer (2). To be clear, James was Rachel’s son.

That night, the Indians did a scalp dance, and Elizabeth and Rachel were gang-raped. The purpose was two-fold: to satisfy the male Comanches’ lust and to humiliate and degrade the women. Whether Cynthia Ann was ever raped is a matter of conjecture. A prepubescent girl when she was abducted, she may have thus been off-limits. Nevertheless, she was stripped, beaten and abused in other ways. Note that adult males usually got the old chop-chop.

Elizabeth was ransomed after a few months. Rachel, pregnant when the attack occurred, had her baby taken from her and murdered before her eyes; Cynthia Ann also witnessed this. She was ransomed and soon dictated a 32-page book entitled Rachel Plummer’s Narrative of Twenty One Months’ Servitude as a Prisoner Among the Comanchee Indians. It was explicit in detailing the cruelty inflicted upon her.

The two boys, John and James, spent five years in captivity before being ransomed. Their freedom, and that of Elizabeth and Rachel, can be traced primarily to the efforts of the indefatigable James W. Parker, who had taken over leadership of the family when his father was killed at Fort Parker. With five of his loved ones seemingly swallowed up by the vastness of the Texas prairie, he was undeterred. Nine times this man entered Comancheria alone. Can you imagine? In the culture of that very martial tribe, bravery and willingness to fight were the most admired of all virtues, and here was a European-American man stalking them! He had some hair-raising experiences and, like Rachel, wrote a book—Narrative of the Perilous Adventures, Miraculous Escapes and Sufferings of Rev. James W. Parker.

willingness to fight were the most admired of all virtues, and here was a European-American man stalking them! He had some hair-raising experiences and, like Rachel, wrote a book—Narrative of the Perilous Adventures, Miraculous Escapes and Sufferings of Rev. James W. Parker.

Let us now return our attention to Cynthia Ann. One of the warriors who descended upon Fort Parker in May 1836 was a young man named Peta Nocona. She had endured four years of captivity when he took a liking to her. Was it reciprocal at first? Possibly. But the dynamics of power in that relationship were obvious, as he had it and she did not. (Similarly, white men and black women often engaged in sex during the days of slavery in the American south. Much of it was coerced, no doubt, but there were exceptions.) For all we know, Peta Nocona may have been one of the gang-rapists of Elizabeth and Rachel. And if he said, “You are mine,” Cynthia Ann was in no position to withhold consent. At any rate, a union was forged in 1840 that resulted in three children: sons Quanah and Pecos, and a daughter, To-tsee-ah or “Little Prairie Flower.”

Slowly forgetting the language, manners and customs of her people, Cynthia Ann was given a new name: Na-u-dah, the meaning of which is “one who is found.” This euphemism simply infuriates me. The girl was not found, she was kidnapped, and to say otherwise is to engage in the worst kind of obfuscation.

It bears remembering that Cynthia Ann had joined the very people who murdered her relatives and tore her from her natural-born society. She spent more than 24 years with the Comanches, and she did to a large degree become part of that culture. She performed the same drudge work as the other women, her light skin and blue eyes notwithstanding. And she was at least peripherally involved in numerous raids against other Indian tribes and European-American settlers. Depredations included scalping, mutilating and torturing.

Because of her marriage to Peta Nocona and giving birth to three kids, Cynthia Ann was an accepted and valued member of this tribe. Her life was not bad. The same might be said of a portion of the hundreds—yes, hundreds—of other settler women who had been abducted and taken west. Some, however, were essentially slaves to be worked from morning to night, berated, abused and raped. It is not my intention to harp on  this, but modern historiography prefers to keep such unpleasantries hidden. Of the European-American women who were recaptured and brought home, many were so shell-shocked from the experience that they could not function. Some bore ghastly tattoos on their faces and/or scars on their backs from having been whipped.

this, but modern historiography prefers to keep such unpleasantries hidden. Of the European-American women who were recaptured and brought home, many were so shell-shocked from the experience that they could not function. Some bore ghastly tattoos on their faces and/or scars on their backs from having been whipped.

Several times during Cynthia Ann’s years with the Comanches, she was located by a scout. They offered to rescue her or have a ransom paid. She, and her husband, adamantly refused. In 1851, her nephew, James Pratt Plummer, had a new role to play. He was sent to meet with Cynthia Ann and ask her to come home. “We miss you,” he said. “Don’t you want to see your momma, your poppa and your sisters and brothers?” It’s impossible to say how conflicted, if at all, she was, but she stayed.

A lot had changed by 1860. Texas had joined the United States, and the frontier kept moving west. Conflicts between Indians and European-Americans were more violent and frequent than ever. James W. Parker relentlessly prodded the Texas Rangers and Governor Sam Houston to bring his niece back, in spite of her refusals. Houston commissioned Captain Lawrence Sullivan “Sul” Ross (who would later become the first president of Texas A&M University) to organize a company of 60 men to halt the Comanche raids and get Cynthia Ann Parker. That is just what happened when they found Peta Nocona’s band encamped on the Pease River, near the Texas- Oklahoma border. The chief was killed, although Quanah Parker later insisted he had survived, and his wife and infant daughter were brought back. She would never see her sons again.

Oklahoma border. The chief was killed, although Quanah Parker later insisted he had survived, and his wife and infant daughter were brought back. She would never see her sons again.

Cynthia Ann’s travails were far from over. A photograph of her, baby at her breast, was taken and widely distributed. European-Americans, especially the families of other abducted women, celebrated the miraculous rescue. Welcomed home as a prodigal daughter, she was never comfortable. After two abortive escape attempts, she was essentially guarded—a bitter irony—by family members and others. She missed her husband and two sons. Pecos died in 1862 and To-tsee-ah two years later. An object of curiosity as the “white squaw,” Cynthia Ann wanted privacy more than anything—except, perhaps, a return to the Indian life to which she had adapted. As the Civil War raged, she slowly regained her mother tongue. Although helpful with chores and adept as a seamstress and spinner, she wept a lot. A neighbor would later recall how she often sat in quiet meditation, oblivious to her surroundings, apparently struggling to suppress powerful emotions.

It’s a wrenching story, and we can understand why her life has been so thoroughly scrutinized. Cynthia Ann Parker has been “claimed” by both the Indian world and the European-American world. It does  seem that the latter has gradually acceded to the former. Why else would the Parkers have allowed her remains to be taken from a cemetery in Anderson County in 1911 by Quanah Parker to his home, the Star House in Cache, Oklahoma?

seem that the latter has gradually acceded to the former. Why else would the Parkers have allowed her remains to be taken from a cemetery in Anderson County in 1911 by Quanah Parker to his home, the Star House in Cache, Oklahoma?

“Forty years ago, my mother died,” he said at her re-interment ceremony. “She captured by Comanches, nine years old. Love Indian and wild life so well she no want to go back to white folks. All same people anyway, God say.”

Enmity, hatred and racism abounded, and through no fault of her own Cynthia Ann—or Na-u-dah—was in the middle of it. Time has afforded a better perspective to all concerned. The passions have cooled, naturally, and each group has stopped demonizing the other. Periodic family reunions in Texas and Oklahoma with both Indians and European-Americans (and, of course, some admixture of the two) involve as many as 100 people, and that has contributed to forgiveness, reconciliation and healing.

8 Comments

Richard, what a wonderful article. My family on my mother’s side are descendants of Cynthia. One of my uncles was fascinated by genealogy and, of course, did it the hard way, as was the only way in those early-mid 1900s. No one else was interested apparently, except for me, and at his death, I inherited his files of research, data, interviews, etc., which concluded in what was a genealogical timeline (with the obligatory so and so begat so and so, etc.). It was an amazing adventure for a small child of the 60’s. Of course, there was no way he could have access to all the historical data now easily available, so his dedication was that much more time-consuming and appreciated. Thank you for this article. I am proud to have native American roots as part of my family’s history. We had numerous clients while in New Mexico who provided me with books, etc., on Cynthia and Quanah. I will send you a pic when I can. Thanks again…keep on writing and wash your hands every so often.

Thanks, Richard. Such a fascinating and sad story and a very interesting rendition by you. I’ve visited Fort Parker several times including bringing our kids to see it on visits to Texas when they were young.

Hi Richard, a couple of years ago I read two first-person accounts of white captives on a university library website. I was stunned, for it was the first time in my life that I had read an account of white captivity that was absolutely nothing like what I was taught in school or read in books and magazines, or had seen in movies. I was so immersed in the obfuscation that in my freshman year of college I even wrote a very one-sided final exam essay on the subject. And so I remained until two years ago. The brutality of the Natives toward their captives was completely shocking to me because I had always been taught that Indians were stoic, but gentle people who loved and respected nature and all living things. I could hardly believe what I was reading – women and girls being gang-raped and/ or used as sex slaves, boys and men being tortured before being killed, captives being treated like slaves if they survived. After reading about Cynthia Ann Parker, I began to wonder privately if she and other captives like her had not wanted to return to their original homes because of Stockholm Syndrome. And then I came across your article which expressed the same thought so now I know I’m not the only one who’s had it. I wish there was a more balanced presentation of history in schools and society because surely every culture has either perpetrated or suffered extremes. People are people, at all times and in all places: the Vikings in Britain, the Roman conquest of Greece, the Visigoths and Ostrogoth destruction of Rome, the Aztec obliteration of the Toltecs, and so on. Thank you for your article.

Well, thank you so much, Pat. I really appreciate your comment, and I agree about how we are not given the whole story. I did a lot of research and put together what I think is an honest appraisal.

Plains indians were noted for their practice of rape, but this was rare in the eastern tribes, i.e. Cherokee, Delaware, handosaunee, Shawnee, etc. Culture differences., for example, matriarchal authority of eastern indian tribes.

This is about Cynthia Ann Parker, not the people who abducted her.

P.S. The English are still hated to this day by many Scots and Irish for the brutal conquest of their countries. But the English were helped by the greedy and treacherous among the Scots and Irish.

Good morning, Richard. I am a descendant of Cynthia and her son, Quanah Parker. My uncle Foy Walling, (on my mother’s side) was into Genealogy. I found it very interesting and, knowing of my interest, he gave me a couple of paperback books about these two ancestors, which I have displayed in one of the bedrooms in our home. It is interesting, indeed, how we come to be who we are.

Add Comment