Hey, Wilbanks Smith, I’m talking to you. I know you are 89 years old and probably fixing to die, but I’m going to give it to you straight. In no way, shape or form do I buy your explanation about what you did  to Johnny Bright in the first quarter of the Oklahoma A&M−Drake football game back in ’51. Not racially motivated, you say. Just hard-nosed football, you say. Didn’t mean to hurt him, you say. Nothing to apologize for, you say. Wrong on all four counts, my dear sir!

to Johnny Bright in the first quarter of the Oklahoma A&M−Drake football game back in ’51. Not racially motivated, you say. Just hard-nosed football, you say. Didn’t mean to hurt him, you say. Nothing to apologize for, you say. Wrong on all four counts, my dear sir!

* * *

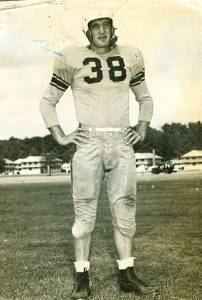

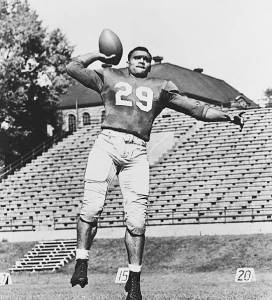

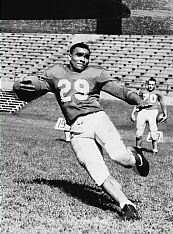

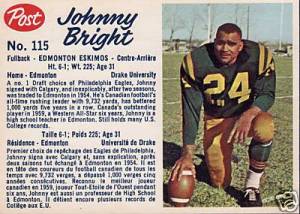

A native of Fort Wayne, Indiana, Bright was big for a quarterback of that era: 6′ 1″ and 215 pounds. One of the first dual-threat QB’s, he thrived under coach Warren Gaer’s single-wing offense. That claim may be quantified as follows. Bright (called “Panda” by teammates because of his bushy eyebrows) led the nation in total offense in 1949 (1,950 yards) and 1950 (2,400 yards, then an NCAA record; 267 yards per game). The Bulldogs were 5-0 entering that contest against the Aggies, and Bright was, if anything, better than  ever. He led the nation in rushing (821 yards) and total offense (1,349 yards). He is said to have had a side-arm throwing motion that was serviceable. In three varsity seasons, Bright would run or pass for 40 touchdowns.

ever. He led the nation in rushing (821 yards) and total offense (1,349 yards). He is said to have had a side-arm throwing motion that was serviceable. In three varsity seasons, Bright would run or pass for 40 touchdowns.

Before going any further, I would like to posit a couple of things. The first is that Bright was one stupendous football player. So why was he at a mid-level school like Drake? I find it hard to believe that nobody in the Big Ten wanted him. The Indiana Hoosiers, representing the flagship institution of his home state, went 6-20-1 during those three years, and he would have surely helped. So there he was at Drake, not exactly a big-time football school. (This situation brings to mind Abner Haynes of North Texas State from 1957 to 1959. SMU, Texas and other Southwest Conference teams did not want him, so he took what he could get. Truth is, they needed him.) The Bulldogs’ quarterback deserved serious attention from all-America listing services and Heisman Trophy voters. Kenny Washington would have understood; UCLA’s studly runner/receiver led the nation in total offense in 1939 but was not a  first-team A-A. I believe Washington, just sixth in Heisman Trophy voting that year, was more deserving than the winner, Nile Kinnick of Iowa. The 1950 Heisman winner was Vic Janowicz of Ohio State, and his numbers look weak when compared to those of Bright. Many voters, presumably European-American, seemed disinclined to recognize black stars.

first-team A-A. I believe Washington, just sixth in Heisman Trophy voting that year, was more deserving than the winner, Nile Kinnick of Iowa. The 1950 Heisman winner was Vic Janowicz of Ohio State, and his numbers look weak when compared to those of Bright. Many voters, presumably European-American, seemed disinclined to recognize black stars.

Bright and Smith were sophomores in 1949 when Drake and A&M met in Stillwater, a 28-0 Aggies victory. It was the first time a black player had competed at Lewis Field, but no problems were reported. The next season, the teams battled to a 14-14 tie in Des Moines. Again, we know of no bad sportsmanship displayed by the visitors, all of whom were European-American. But 1951 was different. In the week leading up to the game, the A&M student newspaper Daily O’Collegian and the Stillwater News Press, imbued with the Jim Crow spirit, called Bright a “marked man.” Coach Jennings Whitworth and his assistants encouraged the Aggies to “get” Bright. Students and townspeople were allegedly placing bets as to when he would be knocked out of the game. Would you be surprised to know that blatant racist terms were used on the A&M practice field and in the locker room?

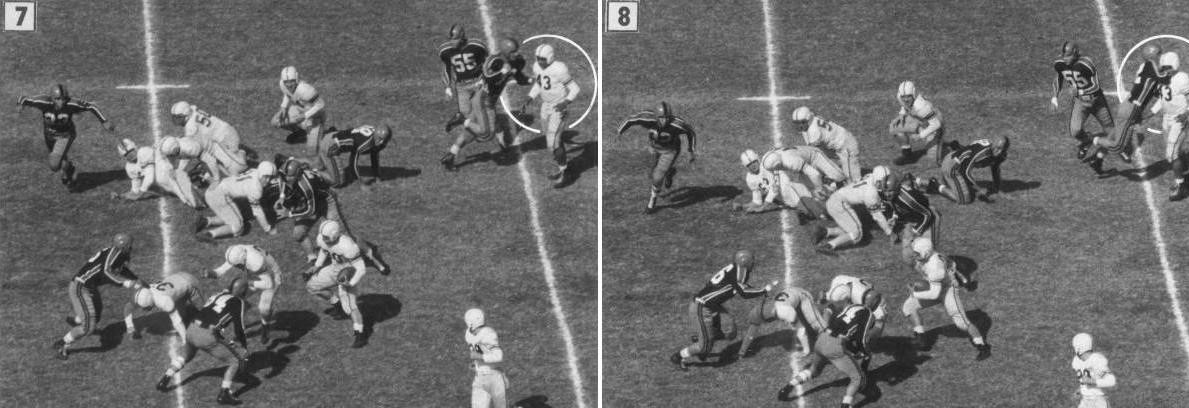

Photographers Don Ultang and John Robinson of the Des Moines Register had heard the rumors, so they kept their cameras focused on Bright. On the first play from scrimmage, he handed off to running back Gene Macomber, retreated a few steps and watched to see how many yards his teammate would gain. Far from the action, Bright  did not realize that the Aggies’ defensive captain was coming at him with bad intent. He hit Bright with a forearm shiver, and the best college football player of 1951—in my opinion—went down. How could he have been knocked unconscious, but the referees called no penalty? This is what happened.

did not realize that the Aggies’ defensive captain was coming at him with bad intent. He hit Bright with a forearm shiver, and the best college football player of 1951—in my opinion—went down. How could he have been knocked unconscious, but the referees called no penalty? This is what happened.

Bright, unaware that his jaw had been broken, staggered to his feet. He took the next snap and threw a 61-yard touchdown strike to Jim Pilkington. Twice on Drake’s next offensive series, Smith targeted Bright. Again, no flags were thrown. Not until he was gang-tackled by most of the A&M defense did he head to the sidelines. The team doctor ascertained that his jaw was busted. With Bright out, the Bulldogs had little chance and fell by a score of 27-14.

If not for the prescience of Ultang and Robinson, the incident would have been quietly forgotten. But the front page of the Sunday Register featured eight sequential photos of Bright handing off and Smith unloading on him. Those pictures, which would win the 1952 Pulitzer Prize for journalism photography, were damning. Life, Time, the New York Times and other publications showed them as well. A torrent of negative publicity descended on Stillwater, and yet Smith was not suspended by Whitworth (who rather confusingly called his shot “illegal but unintentional”), the university or the Missouri Valley Conference.  Drake would later withdraw from the MVC in protest. Smith chose to stonewall. He insisted he had done nothing wrong, Ultang and Robinson’s photos notwithstanding.

Drake would later withdraw from the MVC in protest. Smith chose to stonewall. He insisted he had done nothing wrong, Ultang and Robinson’s photos notwithstanding.

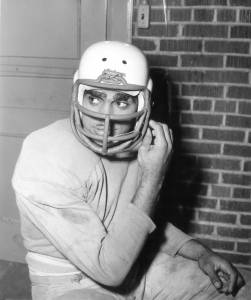

Bright had his jaws wired together and one tooth removed so he could be fed through a straw. He had previously used no face mask, but now he had one that offered protection from other malefactors like Smith. Two weeks later, Bright—was he tough?—played against Great Lakes, running for one TD and passing for two. His coach, Gaer, decided that should be it and held Bright out of the final game. Despite missing 2 ½ games of the 1951 season, he came in fifth in Heisman Trophy voting.

Smith’s college career was over too, but he fell into well-earned obscurity. He served in the military and worked as an engineer in Oklahoma and Arkansas before retiring in Texas.

Bright was chosen by the Philadelphia Eagles in the first round of the 1952 NFL draft, but he stunned a lot of people by going to Canada instead. The Eagles had not yet integrated (although they would that year, with running backs Ralph Goldston and Don Stevens), and their 1951 roster featured players from schools like LSU, Arkansas, Georgia, Texas A&M, Mississippi, Baylor, Alabama, Tulsa, Rice, Georgia Tech, North Carolina, Wake Forest—and Oklahoma A&M. He had a splendid 13-year career north of the border. As a running back with the Calgary Stampeders and Edmonton Eskimos, he gained 10,909 yards. Bright had a superb 5.5-yard rushing  average. In a 2006 poll, he was named one of the top 50 players in CFL history. Although he won the league’s MVP award in 1959, I think he was even better in 1957: 1,679 yards (6.5 yards per carry) and 16 touchdowns. The Eskimos won the Grey Cup three times with Bright carrying the rock.

average. In a 2006 poll, he was named one of the top 50 players in CFL history. Although he won the league’s MVP award in 1959, I think he was even better in 1957: 1,679 yards (6.5 yards per carry) and 16 touchdowns. The Eskimos won the Grey Cup three times with Bright carrying the rock.

The Eagles and other NFL clubs tried to entice him, but Bright enjoyed his life in Canada and stayed. He retired after the 1964 season and became a teacher, coach and principal. Bright was in good health when, in 1983, he chose to have knee surgery. Somehow, he suffered a heart attack on the operating table and died, age 53. The next year, he was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame. An elementary school in Edmonton is named after him.

Things changed in Stillwater. Oklahoma A&M became Oklahoma State (and joined the Big 8 Conference), and the Aggies became the Cowboys. The football program integrated in 1957 with running back Chester Pittman, and OSU  now has an overwhelmingly black roster, as is the case with every other major college program in the country. Wilbanks Smith would not even make the traveling squad today, if he was recruited at all.

now has an overwhelmingly black roster, as is the case with every other major college program in the country. Wilbanks Smith would not even make the traveling squad today, if he was recruited at all.

The university had glossed over the affair for more than half a century when, in 2005, President David J. Schmidly wrote a letter to Drake President David Maxwell, formally apologizing and saying it was “an ugly mark on Oklahoma State University and college football.” Six months later, the field at Drake Stadium was named after Bright. (He had been voted the greatest football player in Drake history in 1969, and that is undoubtedly still so.)

Regarded by some at his alma mater as a pariah, Smith was irked by Schmidly’s apology. He has been reluctant to give interviews because he feels he has been treated unfairly by the media. Yes, he fancies himself a victim.

Regarded by some at his alma mater as a pariah, Smith was irked by Schmidly’s apology. He has been reluctant to give interviews because he feels he has been treated unfairly by the media. Yes, he fancies himself a victim.

* * *

Smitty, you really screwed up. I refer not only to your actions in the 1951 A&M−Drake football game but the aftermath. You should have mitigated the damage by telling the truth from the start. A sincere apology, issued in private to Bright and then publicly would have been appropriate. That would have aided the healing process, and you were in more need of healing than he. You ought to have asked—begged—Bright’s forgiveness. If you had just admitted that you found this stellar black athlete threatening and had committed an unjustified gridiron assault, there would have been a measure of sympathy for you. But nearly 70 years have passed, and you continue to stubbornly assert that you did nothing improper in whacking Bright three times in the first seven minutes of that game. There is catharsis in honesty.

5 Comments

A sad time in our history that we are still witnessing today. 😢 The 2 Georgia rednecks were finally arrested for gunning down a black jogger!

Oh…very different issues.

Richard-A very interesting but sad story that I knew nothing about. Thanks for writing it. Kevin

Thanks, Kevin. I might have added this interesting fact–when Bright died in 1983, a bouquet of flowers came from Wilbanks Smith!

I was later informed by Bright’s daughter that this is incorrect! I heard it somewhere, but not true. Smith sent no flowers….

Add Comment