I am a Gentile, which is to say a non-Jew and a Protestant to boot. So I was born, and I have never felt tempted to alter my religious/spiritual affiliation. One of my female cousins married a Jewish guy, joined him in the synagogue and is technically no longer a shiksa who makes Presbyterian pies. When informed of this by another family member, I retorted, “I wouldn’t do that in 33 million years.” My attitude cannot be traced to anti-Semitism since I am fully aware that Jesus of Nazareth—the anointed one of God—was steeped in the Jewish faith.

That can be said of most of his followers during his earthly life, of the 12 apostles and of Saint Paul, who lost his head in Rome around 67 AD. Christianity, of course, sprang from Judaism. I have often wondered why more modern-day Jews are not persuaded by the Jesus story. You want racial and religious bonafides? He was one of their own, could trace  his family line back to King David, knew the scriptures inside and out, walked on the water, healed the sick, spoke words of profound wisdom and rose from the dead after three days according to the Christian gospel. Are the prophecies from Ezekiel, Isaiah, the Psalms, Zechariah and other books of the Old Testament not compelling? I know that exegesis is a tricky matter and that not all people will agree on the meaning of every line in the Bible; some things are open to interpretation—or flat-out refutation.

his family line back to King David, knew the scriptures inside and out, walked on the water, healed the sick, spoke words of profound wisdom and rose from the dead after three days according to the Christian gospel. Are the prophecies from Ezekiel, Isaiah, the Psalms, Zechariah and other books of the Old Testament not compelling? I know that exegesis is a tricky matter and that not all people will agree on the meaning of every line in the Bible; some things are open to interpretation—or flat-out refutation.

I mentioned above that Paul’s martyrdom occurred in Rome which would soon be the seat of Christendom (at least until the founding of Constantinople and even more so, the Protestant Reformation), the Vatican, the Pope’s residence and so forth. First- and second-century Roman Christians suffered terribly. The present story, set during the fiery days of World War II, took place in Rome as well. The central figure is Israel Anton Zoller, a.k.a. Eugenio Maria Zolli.

He was born in 1885 in the city of Brody, then part of the Austro-Hungarian empire. There were numerous rabbis on his mother’s side of the family, and Zoller, a serious scholar, became one himself. Shortly after his appointment as Chief Rabbi of Trieste, Italy in 1918, he changed his surname to Zolli—less “Jewish” and more “Italian.” He did so because soon after World War I, Italian fascists had begun to make life uncomfortable for Jewish citizens. Twenty years later, Mussolini and his supporters conducted a vicious press campaign against the Chief Rabbi of Rome, David Prato. Zolli replaced him, only to find more trouble. War and repression were brewing, and Zolli thought it prudent to temporarily shutter all public Jewish functions and for the 8,000-member Jewish community to disperse or go underground. Some or perhaps many of his congregants accused him of cowardice, refusing to believe their lives were in such peril. By 1943, with Il Duce deposed and imprisoned (and soon to be shot by firing squad and

He was born in 1885 in the city of Brody, then part of the Austro-Hungarian empire. There were numerous rabbis on his mother’s side of the family, and Zoller, a serious scholar, became one himself. Shortly after his appointment as Chief Rabbi of Trieste, Italy in 1918, he changed his surname to Zolli—less “Jewish” and more “Italian.” He did so because soon after World War I, Italian fascists had begun to make life uncomfortable for Jewish citizens. Twenty years later, Mussolini and his supporters conducted a vicious press campaign against the Chief Rabbi of Rome, David Prato. Zolli replaced him, only to find more trouble. War and repression were brewing, and Zolli thought it prudent to temporarily shutter all public Jewish functions and for the 8,000-member Jewish community to disperse or go underground. Some or perhaps many of his congregants accused him of cowardice, refusing to believe their lives were in such peril. By 1943, with Il Duce deposed and imprisoned (and soon to be shot by firing squad and  ignominiously hung upside down at a gas station with four other unfortunates), the Nazis were in charge in Rome and throughout the country.

ignominiously hung upside down at a gas station with four other unfortunates), the Nazis were in charge in Rome and throughout the country.

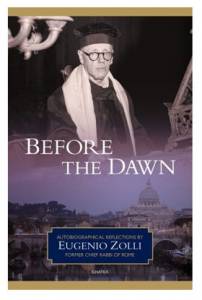

Zolli, whose three brothers died in the Holocaust, had been in hiding in a series of Catholic homes, arranged by Pope Pius XII. (Controversy has swirled around him for decades because he did little to save Jewish lives in this dark time, and yet—as may be seen in the case of Eugenio Zolli—he did not completely sit on his hands. The policies of Pius XII, who was not so much anti-Semitic as pro-German, were governed by the assumption that the Nazis would win the war. As to whether he deserves the epithet “Hitler’s pope,” I do not feel qualified to say.) He finally emerged in 1944 when American forces took possession of the city. Zolli would later write in his autobiography, Before the Dawn, about a vision of Jesus he’d had while presiding over a Yom Kippur service. On February 13, 1945, he, his wife and one of his daughters received the sacrament of baptism in the basilica of St. Mary of the Angels and Martyrs and were incorporated into the mystical body of Jesus Christ. But this was no sudden decision. Zolli had in fact been studying and writing about what might be called Christian issues for at least 15 years. His book Il Nazareno, came out in 1938; try to imagine the shock among Jews when a promiment rabbi wrote a volume about Jesus Christ or “Rabbi Yeshua.” He would emphasize that nobody had proselytized to him or tried to convert him. It was a slow, evolutionary and wholly internal process by which he embraced Christianity.

Out as the Chief Rabbi, he taught at a local college and the Pontifical Biblical Institute. Zolli had ample opportunity to state just what he had done and why. Yes, he had made a momentous break, one that  caused the Roman Jewish community to turn bitterly against him and call him an apostate, a heretic and a traitor. Prato, whose place he had taken in 1939, was back. He proclaimed a fast of several days to atone for Zolli’s defection, and local Jews mourned him as though he were dead. “Members of the tribe” were forbidden to speak his name, a Jewish weekly was published with a black cover, and insults and threats became the norm for his family. The New York Board of Jewish Ministers did its best to discredit Zolli. Among other things, it sent a letter to its membership before Passover 1945 which read in part, “The apostasy of the ‘rabbi’ of Rome must be made known to our people as an act of desertion.”

caused the Roman Jewish community to turn bitterly against him and call him an apostate, a heretic and a traitor. Prato, whose place he had taken in 1939, was back. He proclaimed a fast of several days to atone for Zolli’s defection, and local Jews mourned him as though he were dead. “Members of the tribe” were forbidden to speak his name, a Jewish weekly was published with a black cover, and insults and threats became the norm for his family. The New York Board of Jewish Ministers did its best to discredit Zolli. Among other things, it sent a letter to its membership before Passover 1945 which read in part, “The apostasy of the ‘rabbi’ of Rome must be made known to our people as an act of desertion.”

Some critics claimed he had done it to make an easier life for himself or to appease his Christian friends; more than an apostate, he was cynical and opportunistic. After all, Christians had been trying to convert Jews for centuries. Might he be like one of those crypto-Jews who had faked conversion after Ferdinand and Isabella sought to reconstitute Spain as a fully Christian country in 1492? Not a chance. Zolli was a courageous man of conscience who eloquently clarified why he had acted. He explained, to both the Christian and Jewish communities, his conversion: “In the Old Testament, justice is carried out by one man towards another…. We do good for good received; we do harm for harm we  have suffered at the hands of another. Not to do injury for injury is, in a certain fashion, to fall short of justice. What a contrast with the gospel—Love your enemies and pray for them, or even Jesus’ last words on the cross: ‘Father, forgive them, for they know not what they are doing!’ All this stupefied me. The New Testament is, in fact, an altogether new covenant.”

have suffered at the hands of another. Not to do injury for injury is, in a certain fashion, to fall short of justice. What a contrast with the gospel—Love your enemies and pray for them, or even Jesus’ last words on the cross: ‘Father, forgive them, for they know not what they are doing!’ All this stupefied me. The New Testament is, in fact, an altogether new covenant.”

In response to those who accused him of abjuring the Hebrew nation, Zolli said, “I have not given it up. Christianity is the completion of the synagogue. The synagogue was a promise, and Christianity is the fulfillment of that promise…. What I converted to was the living Christianity.”

Zolli, whose life abounded with both tragedy and heroism, contracted pneumonia, was hospitalized and died in Rome on March 2, 1956. He was buried in the Cimitero Comunale Monumentale Campo Verano; a cross adorns his marker. With Pius XII dead two years later, he had few defenders outside of his family. Zolli dropped into obscurity, and his writings were neglected until a new edition of Before the Dawn—full of insights (some of them humorous) about ecumenical matters, mysticism, the law, the gospel and what it meant to be a “completed Jew”—was published in 2004. It sold well, leading to his rediscovery by scholars and the general public.

10 Comments

“synagogue was a promise, and Christianity is the fulfillment of that promise” says it all. I also was struck with the simplicity of his transition from non christian jewish faith to Christianity and being a Catholic, meaning, it was gradual, he was seeking, and he found. That is also a truth that Jesus taught, “Seek and ye shall find”. As to his fear of the Nazi’s, and the name change, I can’t be a judge, but, the name change turned out to be a good idea. If he hadn’t, he would be like the other 6 million Jews of the holocaust, good for him.

Gary, one thing I might have mentioned in this article is that in March of this year (2020) the Vatican will release a lot of previously classified documents about Pope Pius XII. We will surely learn some interesting stuff there. As for Zolli, I really admire and respect him. What comes first–being a member of the tribe or one’s conscience?? I say shame on all those Jewish people who shunned and criticized him. He acted on his sincere beliefs.

I am a devout Catholic, but I had not heard of him. I think they are called ‘completed Jews’, but I am not sure. Compelling story though, thank you!

The story is not widely known, Kenny. Jews want to forget about it, and Christians are sensitive to their feelings and so nobody speaks of Zolli. I mentioned “completed Jews” in the final paragraph.

very interesting; I have never heard of this man. I am sure that his words and deeds are hidden from the public. I am curious about the release of the popes writings. Thanks for this interesting information.

Very true. I wonder what we will learn about PP 12 (and about Zolli) when those papers are released!

Very interesting story that I was not aware of. Obviously a very devout, thoughtful man who was able to critically question the dogma he grew up with.

It sure is, Kevin. There had been some problems between him and local Jews in the 1930s, even before he got to Rome. This was definitely a gradual process, nothing sudden–although he did claim to have that vision of Jesus during Yom Kippur. Pretty interesting!!!

Thanks for another intriguing story, Richard. I am hesitant to condemn anyone’s religious conversion, regardless of the circumstances. I accept it as part of one’s faith journey, which should not be limited to membership in a formal, organized religion.

You are right, Bob. In the case of Zolli, it seems quite sincere. As to my fem cousin, who knows? Doing it to please her hubby is hardly the same as what Zolli went through.

Add Comment