I spent most of 1995, 1996 and 1997 researching, writing and nudging Longhorn Hoops / The History of Texas Basketball toward publication. Funded on the cheap by the UT athletic department, it was brought out in 1998 by UT Press. I was in touch with a lot of people during those three years, the most prominent being Dr. Denton Cooley. No former Texas basketball player, Kevin Durant included, approaches the renown of this man who was born in 1920 and died 96 years later.

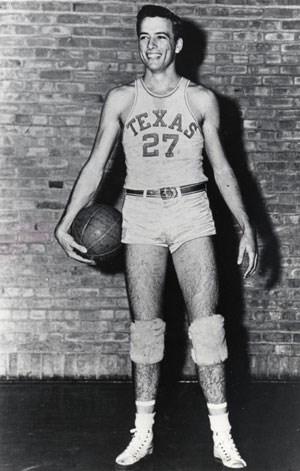

I went to Houston to interview him about his days in orange and white. We met in his office, situated deep inside the palatial Texas Heart Institute (THI) which he began in 1967. Standing 6′ 4″ and still slim, he looked like he had played a lot of basketball in his youth. Cooley, dressed in light-blue “scrubs” suitable for the operating room, was glad to reminisce about playing on the Gregory Gym hard courts and spirited games against such teams as the Arkansas Razorbacks, Rice Owls and Texas A&M Aggies, not to mention UT’s winning the 1939 Southwest Conference championship and taking part in the first NCAA tournament. We discussed how he had gone from unheralded walk-on to three-year letterman for Jack Gray’s Horns. Busy as Cooley was, he gave me all the time I wanted. I estimate that I have conducted 1,500 interviews in my journalism career, and few have been more pleasant.

My questions answered and every topic covered, I had begun to say goodbye. Cooley undoubtedly had some surgical or administrative matters to handle. First, however, he said he wanted to show me something. This man, awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Ronald Reagan, named one of UT’s Distinguished Alumni, winner of the René Leriche Prize and too many other honors to list here, pulled up his shirt and displayed his chest. I saw the interlocked letters “U” and “T,” resulting from the placement of a red-hot brand during an initiation rite by the Texas Cowboys almost 50 years earlier. Cooley smiled and recalled the pain as well as a feeling of camaraderie and brotherhood.

He first planned to follow in the footsteps of his father, a dentist, but that quickly changed. After graduation, Cooley headed to Galveston and enrolled at the UT Medical Branch. He found the level of education lacking and transferred to a far better school, Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. His MD was granted in  1944. Despite specializing in heart surgery, he was called upon to do all sorts of operations during a two-year military stint right after World War II. He returned to Houston and began working with Dr. Michael DeBakey at Baylor College of Medicine and its affiliate institution, Houston Methodist Hospital. Cooley later moved his practice to St. Luke’s Hospital before founding THI. These are just a few of his accomplishments:

1944. Despite specializing in heart surgery, he was called upon to do all sorts of operations during a two-year military stint right after World War II. He returned to Houston and began working with Dr. Michael DeBakey at Baylor College of Medicine and its affiliate institution, Houston Methodist Hospital. Cooley later moved his practice to St. Luke’s Hospital before founding THI. These are just a few of his accomplishments:

- While at Johns Hopkins, he helped Dr. Alfred Blalock repair a malformed blood vessel in the first successful “blue baby” operation;

- He developed a new way to remove aortic aneurysms;

- He and his colleagues pioneered artificial heart valves;

- He reduced the need for blood transfusions in heart surgery;

- By age 50, he had performed more than 5,000 cardiac operations;

- He wrote or co-wrote some 1,400 academic articles and eight books;

- He helped DeBakey create the polyethylene terephthalate (Dacron) fabric that is used even today as graft material in heart surgery;

- He performed the first successful heart transplant in the United States (six months after Dr. Christiaan Barnard had done so in South Africa); and

- He implanted the world’s first artificial heart.

The latter achievement, on April 4, 1969, was fraught with controversy. DeBakey insisted that device was his, although he had designed it in conjunction with Dr. Domingo Liotta, and Liotta was ready to see it put to use. In an era of scant governmental oversight of medicine, not everybody agreed with Cooley’s  bold move forward. (The device worked for 32 hours before a donor heart could be found, and the patient nevertheless died soon thereafter of renal failure and acute pneumonia.) Cooley was censured by the American College of Surgeons, but that was of little consequence in his long and brilliant career.

bold move forward. (The device worked for 32 hours before a donor heart could be found, and the patient nevertheless died soon thereafter of renal failure and acute pneumonia.) Cooley was censured by the American College of Surgeons, but that was of little consequence in his long and brilliant career.

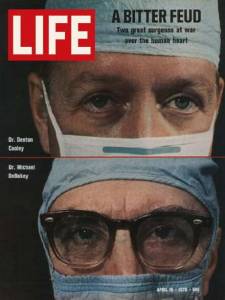

What is most remembered is that the incident sparked an almost 40-year feud between him and DeBakey. Both giants in the field of heart surgery, both based in Houston and both possessed of a healthy ego, they ignored each other or sniped at each other until a Cooley-instigated reconciliation took place in 2007. (Drs. Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin, each of whom made great strides in finding a cure for polio in the 1950s, had engaged in a similar long-running feud.) DeBakey died a year later and Cooley in 2016.

Let me return to the Longhorn Hoops story. There was a critical time when the book’s publication was in doubt, as athletic director DeLoss Dodds—who had commissioned it—seemed to be wavering. Bill Wendlandt, MVP of the 1983 team and by then successful in the field of commercial real estate, put up some of his money and came with me to a meeting in Dodds’ office at Bellmont Hall. “DeLoss,” he said, “this is an important book, and it really deserves to be published.” Furthermore, he knew Cooley and called him. He agreed to make a similar donation as well as to write the book’s foreword, in which he quoted Teddy Roosevelt’s timeless prose: “It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them  better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena…who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”

better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena…who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”

The people in the Texas athletic department had been scarcely aware of Cooley and his contributions to the basketball program from 1939 to 1941. My book came out, and soon someone employed in “development” was driving to Houston. The good doctor was convinced to write a check significant enough for his name to be put on a two-level, 44,000-square-foot practice and training facility adjoining the Erwin Center. The Denton A. Cooley Pavilion opened in 2003, and Wendlandt always said it happened because of the book.

Add Comment