Marching and picketing, sit-ins, court rulings, freedom rides, grassroots activism, soaring oratory, physical resistance and fervent prayers contributed to the success of the civil rights movement. But minor league baseball also helped eliminate racial barriers below the Mason-Dixon Line. The sight of Afro-Americans and Euro-Americans playing together on teams from Maryland to Texas had a huge impact on softening attitudes, disproving stereotypes and signaling the demise of Jim Crow. It was a much-needed democratizing influence.

In 1947, Jackie Robinson proved himself with the Brooklyn Dodgers, followed quickly by Larry Doby with the Cleveland Indians. Several more, such as Hank Thompson, Willard “Home Run” Brown, Monte Irvin and Sam Jethroe, made a lateral move from the Negro Leagues. But every major league team resided up north (and so it remained until the Houston Colt .45s first took the field in 1962), and many minor league clubs were down south.  Integration of minor league ball there could not be put off forever. None expected it to be easy in this land of the Old Confederacy, racial violence and bigotry—not to paint with too broad a brush. We can look back 60 or 70 years and see drama, conflict, some surprises and not a little glory.

Integration of minor league ball there could not be put off forever. None expected it to be easy in this land of the Old Confederacy, racial violence and bigotry—not to paint with too broad a brush. We can look back 60 or 70 years and see drama, conflict, some surprises and not a little glory.

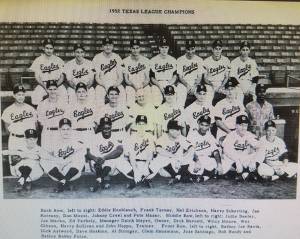

The most significant minor leagues in the south then were the Carolina League (whose pioneer was Percy Miller of the Danville Leafs in 1951), the South Atlantic or “Sally” League (Hank Aaron, Horace Garner and Felix Mantilla of the Jacksonville Braves, and Junior Reedy and Albert Israel of the Savannah Indians in 1953), the Southern Association and the Texas League. The Southern Association, consisting of the Atlanta Crackers, Birmingham Barons, Chattanooga Lookouts, Little Rock Travelers, Memphis Chicks, Nashville Vols, Mobile Bears and New Orleans Pelicans, stubbornly resisted integration and paid the price by folding in 1961. That brings us to the  Texas League, whose members were the Houston Buffaloes, Beaumont Roughnecks, Tulsa Oilers, Oklahoma City Indians, San Antonio Missions, Shreveport Sports, Fort Worth Cats and Dallas Eagles.

Texas League, whose members were the Houston Buffaloes, Beaumont Roughnecks, Tulsa Oilers, Oklahoma City Indians, San Antonio Missions, Shreveport Sports, Fort Worth Cats and Dallas Eagles.

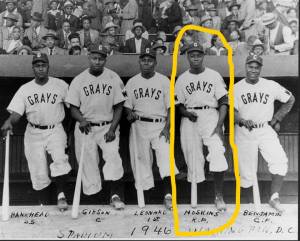

The Eagles played at 10,500-seat Burnett Field in Oak Cliff, on the south bank of the Trinity River. Their owner, oilman Dick Burnett, had to act because attendance was dropping. He did not want a novelty but a legitimate ballplayer. Burnett, genuinely upset about the unfair treatment of black Texans, is proof that not all southern honks were bad. The guy had a social conscience! As none of the other owners were in a hurry to integrate, without Burnett the Texas League might have followed the Southern Association into oblivion. He got the right man—an outfielder-turned-pitcher named Dave Hoskins. Born in Mississippi in 1917 (he found it expedient to claim 1925), he grew up in Flint, Michigan. Hoskins, standing 6′ 1″ and weighing 180  pounds, already had 10 years of pro baseball experience, with the Ethiopian Clowns, Homestead Grays (he was a teammate of the great Josh Gibson), and minor league clubs in Grand Rapids, Dayton and Wilkes-Barre. Hoskins brought a lot of moxie to the Eagles, although his fastball was not overpowering. He had fine control and threw a wicked curve.

pounds, already had 10 years of pro baseball experience, with the Ethiopian Clowns, Homestead Grays (he was a teammate of the great Josh Gibson), and minor league clubs in Grand Rapids, Dayton and Wilkes-Barre. Hoskins brought a lot of moxie to the Eagles, although his fastball was not overpowering. He had fine control and threw a wicked curve.

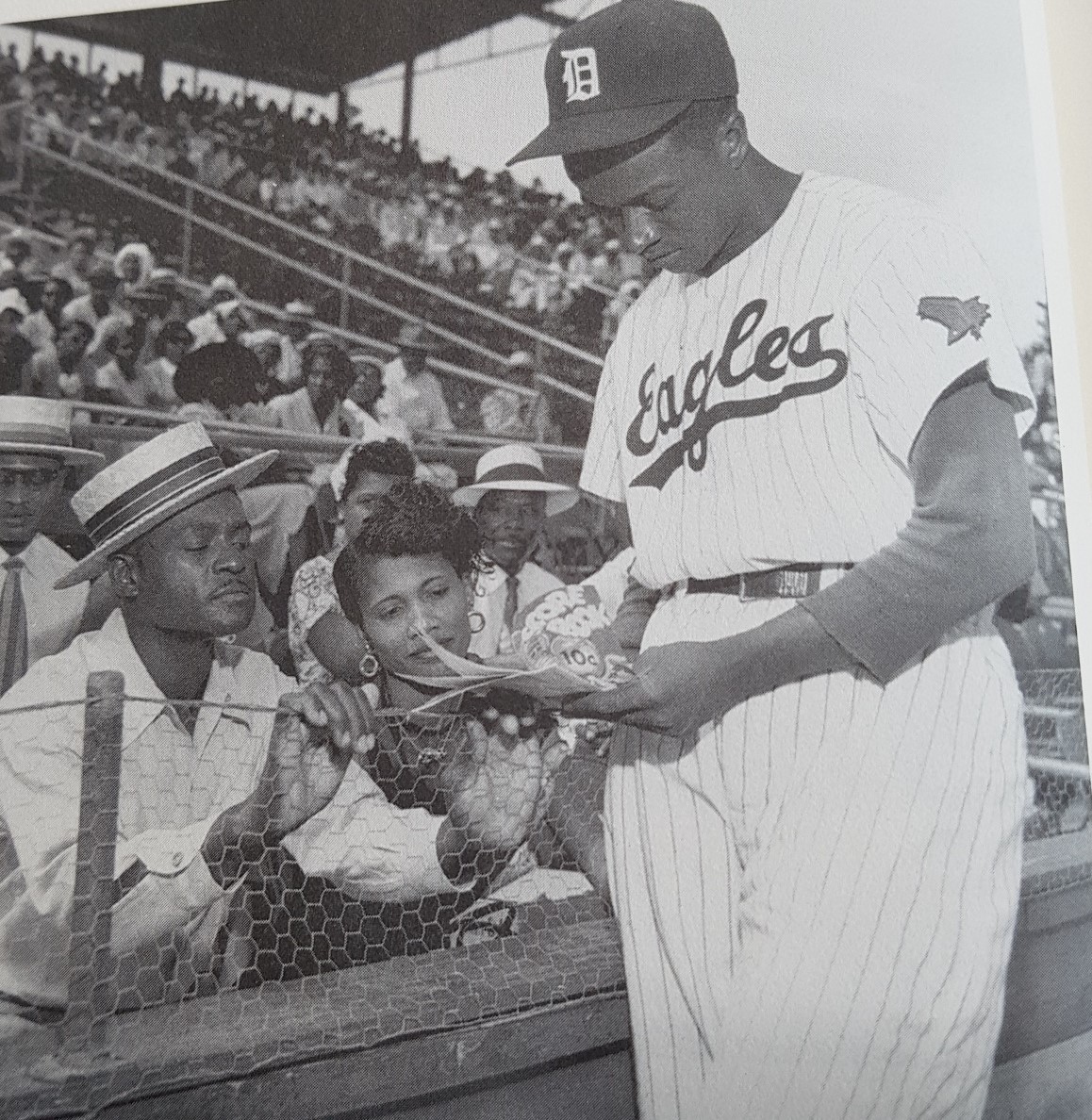

Dallas caught lightning in a bottle with Hoskins, then 35 years of age. He went 22-10 with a 2.12 ERA (and hit .328, often playing right field when he was not on the mound), made the All-Star team and led the Eagles to the 1952 Texas League title. Oh, did I mention that he was responsible for a big jump in attendance at both home and away games? Before integration, few black fans went to league parks and sat in the restricted areas. Now, with the opportunity to see one of their own they showed up in big numbers—sometimes making up half of the crowd. People who knew him  recall that Hoskins freely signed autographs for fans, both Afro-American and Euro-American. A model of decorum, he did his share of attending community events and spoke freely with local sports writers.

recall that Hoskins freely signed autographs for fans, both Afro-American and Euro-American. A model of decorum, he did his share of attending community events and spoke freely with local sports writers.

Of course, it was not easy for this baseball trailblazer. The Eagles’ best player, he was also its lowest-paid. Some Euro-American teammates ignored him, and he endured rough treatment from opponents and catcalls from the stands. Hoskins never lost his composure, even when he got death threats before the Eagles’ visit to Shreveport on June 9. Not even bothering to inform his manager, Dutch Meyer (nephew of the TCU football coach of the same name), he went out and won the game, 3-2.

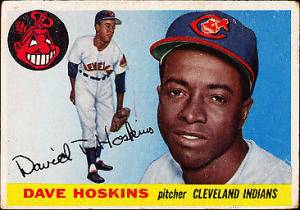

The Eagles’ major league affiliate was the Cleveland Indians, and the Tribe’s general manager, Hank Greenberg, had been responsible for signing Hoskins and sending him to Dallas. Although Cleveland  already had an excellent rotation, he brought Hoskins up in 1953. He went 9-3, but a sore arm soon had him back in the minors. After retirement, Hoskins returned to Flint and worked in that city’s automobile factories, dying of a heart attack on April 2, 1970. Despite playing 19 seasons of pro ball for no fewer than 17 teams and being the key figure in integration of the Texas League, Hoskins was mostly forgotten.

already had an excellent rotation, he brought Hoskins up in 1953. He went 9-3, but a sore arm soon had him back in the minors. After retirement, Hoskins returned to Flint and worked in that city’s automobile factories, dying of a heart attack on April 2, 1970. Despite playing 19 seasons of pro ball for no fewer than 17 teams and being the key figure in integration of the Texas League, Hoskins was mostly forgotten.

The grim reaper had also come for Burnett, in 1955, at age 57. This man, full of energy and ideas, may well have stolen a march on Roy Hofheinz. It was he who convinced major league baseball to allow him and his Houston partners to buy a franchise, starting with the 1962 season. Had Burnett lived, he would have pushed hard for that plum to be awarded to Big D, or perhaps one for each of Texas’ two major cities. In fact, before his death Burnett was in negotiations with at least one big league franchise to come to Dallas and was talking up a new stadium north of the river.

14 Comments

Richard:

Your research and detail are outstanding. A great story with wonderful photos.

Thanks,

Rex

Thank you, Rex!!

I’m Lynda Hoskins the daughter of the amazing David Hoskins. My father die of a heart attack April 1970. My father was a hero in many eyes, he fought hard for his rights and the rights of others without any prejudices. It’s very sad for someone to spread such a heinous lies about such a great man. In all the comments that I have read about my father you’re the only one that wrote such a statement. You need to read and understand what you read before you make such a statement. Have a very Bless Life.

I apologized to you sir, I was replying to a comment that someone made about my father committed suicide. I meant no harm, I appreciate everyone that loved and admired him.

Richard,

I really loved the articles and the photos that you share of my dad. You really spent a lot of time and energy doing research and writing’s on him. I just wish that they would had not forgotten him, like someone mentioned. Maybe we can all get together and chat, my son has contact with Jason. My son’s number is ## David Hoskins #810 -308 -6967. I would love to have a movie made of my father, he did made history.

I read he was 44 and died while in his taxi. Great athlete though. Thank you for a good story!

Forty-four was based on the erroneous birth date he used. Had it not been for the racism of the day, Hoskins would have had a long and successful big league career and would be remembered today.

I was unaware of this team. Wow. Great insights, stats and cmprehension of the circumstances at the time he played.

Gary, I went to 2 or maybe 3 games there. Wish it had been more… There was an event where a lot of kids’ church baseball teams (including Casa Linda Presby) gathered for photos and I wish I knew what else, circa 1962. And the stadium had been torn down but lay there in rubble for several years. Since my maternal grandmother lived on nearby Lancaster Street, I went there and looked around. A lot of baseball history and social history took place at Burnett Field.

Thank you for the article. I learned about Dave Hoskins from Mudcats’s book “Black Aces” and was inspired to write an article on him a few months ago for the SABR Baseball Cards blog. Things came full circle for me in that I just got off the phone with his grandson!

Thanks, Jason. I would very much like to talk to Hoskins’ grandson too. I hope you sent him my article.

I’m Lynda Hoskins, the daughter of the late David Hoskins . My son and I talk about your conversations. I would love to chat with you .

810 -3086967

Hi Richard — sharing your story on the Historical Negro League facebook page.

Nice work!!

I’m Lynda Hoskins, the daughter of the late David Hoskins . My son and I talk about your conversations. I would love to chat with you .

810 -3086967

Add Comment