It was liberation day—the defeated Japanese having begun a hasty exit from Korea 74 years ago—and President Moon Jae-in, in a pale blue hanbok, was addressing the nation from Independence Hall in Cheonan. I saw him on the TV from my seat at the rear of a south-bound bus. We got to Goheung, situated on a peninsula in South Jeolla Province, in mid-afternoon. I found a hotel room and immediately turned on the air conditioning; this three-day trip would be characterized by heat.

The merciless sun notwithstanding, I walked all over downtown Goheung. I took note of the county government building, the market and a café called Merci (French for “thank you”). The front window featured some simple and yet profound advice in the form of a poem. Entitled “Take Time,” it went like this:

Take time to work. It is the price of success.

Take time to think. It is the source of power.

Take time to play. It is the source of perpetual youth.

Take time to read. It is the fountain of wisdom.

Take time to love. It is the highest joy of life.

Take time to be friendly. It is the road to happiness.

Take time to laugh. It is the music of the soul.

Take time to dream. It is hiching [sic] your wagon onto a star.

The funerary markers which dot every city- and landscape in Korea say unambiguously, “We respect our ancestors.” But there are so many of these, some fall into neglect and disrepair. Noting one such halfway up a mountain in Goheung, I climbed and took a close look. There were several graves, covered by  weeds and choked with trash. I realize it would cost money, but I wish the local government had some kind of task force that knew of these places and could give them a good clean-up. This, I aver, should be done throughout the country on a regular basis; thrice a year sounds reasonable.

weeds and choked with trash. I realize it would cost money, but I wish the local government had some kind of task force that knew of these places and could give them a good clean-up. This, I aver, should be done throughout the country on a regular basis; thrice a year sounds reasonable.

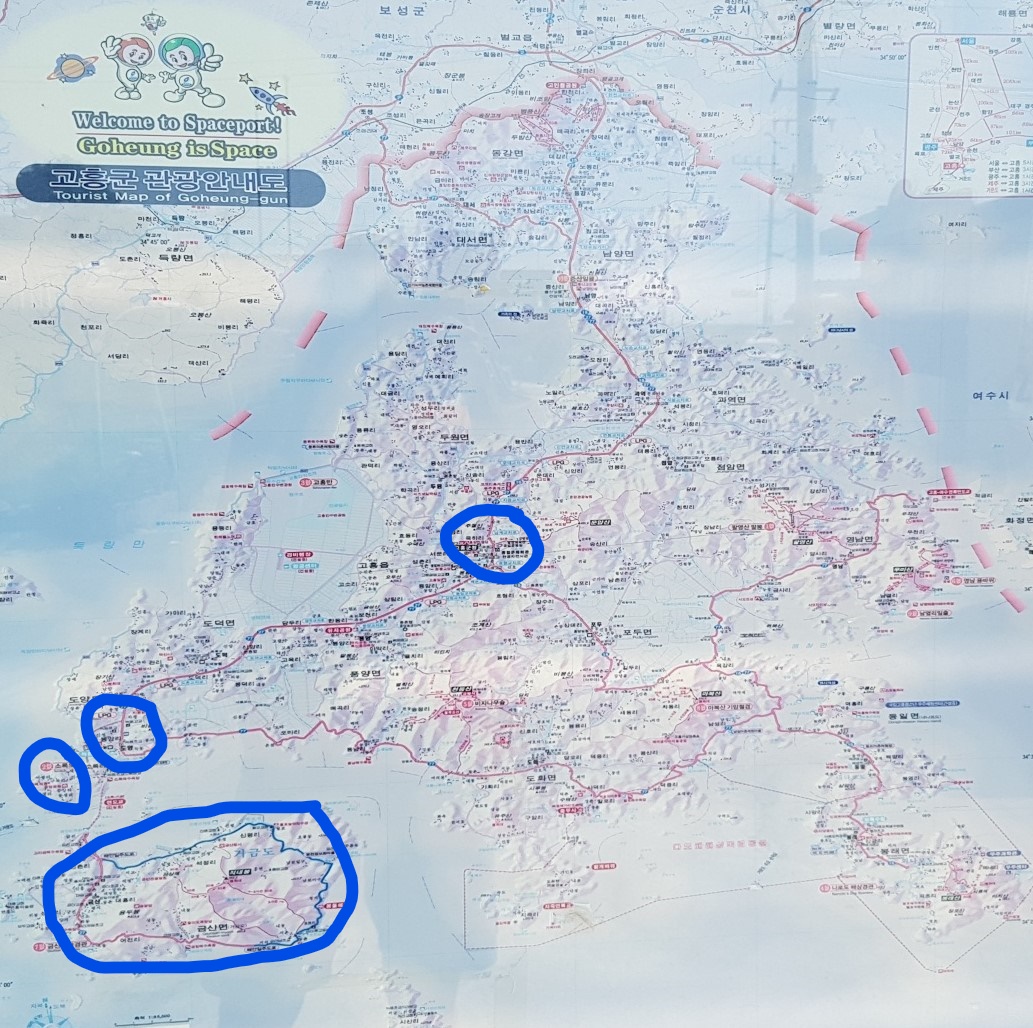

One thing not on my itinerary but worth seeing was the Naro Space Center, operated by the Korea Aerospace Institute (itself under the Ministry of Science and Information and Communication Technologies). Located on an island off the southeast coast, it has an exhibition hall, two launch pads, a control tower, and facilities for research, assembly and testing of rockets. The Naro Space Center opened about a decade ago and has seen just four launches—two failures, followed by two successes. Building a space program is not easy (or cheap) under any circumstances, and especially so in this case because of political pressure from the United States. The Americans fear that if South Korea had the ability to launch rockets and missiles with indigenous  technology, military applications would inevitably ensue. To which I reply, so what? Among the big news stories during my trip was that the DPRK had shot off two more short-range missiles, for a total of 12 in the last three weeks. Again and again, I saw Kim Jong-un and his generals roaring with delight.

technology, military applications would inevitably ensue. To which I reply, so what? Among the big news stories during my trip was that the DPRK had shot off two more short-range missiles, for a total of 12 in the last three weeks. Again and again, I saw Kim Jong-un and his generals roaring with delight.

I got up early Friday morning and rode a bus about 20 kilometers to Nokdong, a colorful port with fishing boats jamming the harbor. Although I did not know it at the time, I would end up spending the night there because Sorok-do had no hotels. This was my real destination, the reason I had come so far. Since the next bus did not leave for two hours, I used my time well. I sat in a convenience store and read the voluminous papers I had brought about the history of this small (4 1/2 square kilometers) island, home to barely 1,000 people. Soon after the Japanese takeover in 1910, they brought all sufferers of leprosy—scientific name: Hansen’s disease—to Sorok-do and instituted rigorous measures of quarantine. That disfiguring nerve and skin ailment had long caused stigma and prejudice,  compounded by the Japanese’ haughty assumptions of superiority over the natives. Sorok-do had all the ingredients for cruelty and blatant human rights abuses. Several former residents called it “hell on earth.” Their hopes for better days with liberation in 1945 soon vanished because the Korean administrators and doctors who moved in, with some exceptions, were just as bad. Not until the 1960s did improvements come. Part of that process was the arrival of two Catholic nurses from Austria, Marianne Stoger and Margareth Pissarek. These blue-eyed angels stayed 43 and 39 years, respectively. They treated the patients with bare hands, procured medicine and oversaw the construction of much-needed facilities.

compounded by the Japanese’ haughty assumptions of superiority over the natives. Sorok-do had all the ingredients for cruelty and blatant human rights abuses. Several former residents called it “hell on earth.” Their hopes for better days with liberation in 1945 soon vanished because the Korean administrators and doctors who moved in, with some exceptions, were just as bad. Not until the 1960s did improvements come. Part of that process was the arrival of two Catholic nurses from Austria, Marianne Stoger and Margareth Pissarek. These blue-eyed angels stayed 43 and 39 years, respectively. They treated the patients with bare hands, procured medicine and oversaw the construction of much-needed facilities.

I arrived on the island and was informed by a guard as to just where I could and could not go. In fact, tourists like me were not allowed to see too much since the privacy of the patients (now fewer than 600 with an average age of 76) was paramount. I was able to visit a couple of red-brick buildings that made my blood run cold regardless of the heat. One was an H-shaped detention center and the other was where operations and autopsies had taken place. I met another tourist, a Korean woman named Kyung Ok-hwa. She and I walked through Sorok-do’s Central Park—built under compulsion by the patients in the 1930s and early 1940s—and a very informative museum. It depicted not just the unfathomable mistreatment the people endured but the various ways they tried to forge a community. They published a literary magazine, they wrote  Chinese poems, they had athletic contests, they married (only after the authorities, believing leprosy to be an inherited disease, performed vasectomies on the men) and provided each other with burial services. Despite their miserable conditions, these people were not completely docile. Protests happened now and then. One imperious Japanese administrator, Masato Suo, had a statue of himself built and ordered the people to bow before it. He also carried a bamboo cane and did not hesitate to whack men, women and children if he thought they were malingering. Well, in 1942 an inmate named Lee Chun-sang had enough and stabbed Suo to death. Needless to say, he was soon executed. Suo’s statue is gone, but one of Lee is today given a position of prominence at Sorok-do.

Chinese poems, they had athletic contests, they married (only after the authorities, believing leprosy to be an inherited disease, performed vasectomies on the men) and provided each other with burial services. Despite their miserable conditions, these people were not completely docile. Protests happened now and then. One imperious Japanese administrator, Masato Suo, had a statue of himself built and ordered the people to bow before it. He also carried a bamboo cane and did not hesitate to whack men, women and children if he thought they were malingering. Well, in 1942 an inmate named Lee Chun-sang had enough and stabbed Suo to death. Needless to say, he was soon executed. Suo’s statue is gone, but one of Lee is today given a position of prominence at Sorok-do.

Ok-hwa and I walked out of the museum and saw a man sitting in a motorized wheelchair. The only patient I encountered during my visit, he may have been there for a purpose—hoping to catch the eye of tender-hearted visitors. I had no problem with that and was pleased when he accepted the 5,000 won bill I proffered.

The same guard whom I had met three hours earlier gave Ok-hwa and me a ride back to the mainland (Nokdong). We said goodbye, and the remainder of the day consisted of me walking the streets and sometimes ducking into a shop to cool off. Nighttime featured a  well-attended music-and-dance performance on a pavilion in the harbor. As much as the show, I liked watching kids zoom around on scooters that flashed different colors.

well-attended music-and-dance performance on a pavilion in the harbor. As much as the show, I liked watching kids zoom around on scooters that flashed different colors.

On Saturday morning, I went to the bus station and bought a ticket to Geogeum-do, a much larger island southeast of Sorok-do. I really did not know what I might see there, but it was my one opportunity to go. When might I be back? I sighed as we passed through Sorok-do and then settled in for a long ride. At one point, a kind lady used the translation app on her smart phone to ask me where I was going. Nowhere in particular. I was content to look out the window as we traversed the island. There came a point when she and the others had debarked, leaving just me and the driver. At a  village called Ocheon, he turned off the engine and said our return trip would commence in 30 minutes. That gave me time to walk down to the shore, watch the waves of the South Sea roll in and take a couple of selfies. I stopped at a desacralized church (built in 1975) and wondered about its history in this remote place. The driver returned at the appointed time, and off we went.

village called Ocheon, he turned off the engine and said our return trip would commence in 30 minutes. That gave me time to walk down to the shore, watch the waves of the South Sea roll in and take a couple of selfies. I stopped at a desacralized church (built in 1975) and wondered about its history in this remote place. The driver returned at the appointed time, and off we went.

In Nokdong, I paid 9,000 won for a fish dinner, with rice and 11 side dishes. The bus to Seoul left at 3:30. On the way up, I thought about the people—dead and still living—who have called Sorok-do home over the last 110 years.

5 Comments

Thank you dear bro for sharing this poem. I have read this before somewhere. Yes,

spend ing time with ourself is time well spent because it makes us a happier person to be around. Spending time with ourself benefits everyone because by having a happier and healthier mindset, we are in a better frame of mind to take care of the people who are important to us

Dr. Cornel, we should all “take time.”

Yes , i agree that the government should allocate budget in the maintenance of public cementeries as they are an indication of how we respect those who were gone ahead of us. I wish the government will do something not only in Korea but to my country as well.

And your kindness exudes wherever you go. Well done dear bro!

I can’t tell you how much it upsets me to see those old, gracious places being ignored and abused. Glad you agree with me!

He is the last person I would ever expect to run into on a narrow and wobbly plank bridge. Rumor has it among the kids in town that he is a kid-eating monster without nose, fingers, and toes.

I don’t have a clear recollection of how old I was at that time. All I remember was that I wasn’t old enough to tag along with the neighborhood buddies to where they were going. I was too scared to go across the plank bridge going over a disgusting creature-infested river. Truth be told, walking over the old crumbling bridge itself was an impossible challenge.

By no stretch of my imagination, do I believe I was thinking clearly that day. Actually, I don’t remember how or why I got there. Now, I’m just stuck in the middle of the wobbly plank bridge, totally frozen, my feet riveted on the cracked planks. I can’t dare to move forward or backward. If I got a bit off balance I’d fall in the river. In despair and hopelessness, I’ve just burst out into cry.

Somewhere up the river was a leprotic people’s hut. Nobody knew where they’d come from or when the hut had been built, except that they’d been ostracized somewhere. When one or two of them came to town to beg for scraps of food, they were always covered in dirty rags with unusually shining eyes that delivered feelings of fear and sorrow. Being aware that they could have been kicked out or stoned at by scared kids any time they must have been as fearful of people as the kids were of them. The only business they had in the town was to get food and get out quickly. Despite their low-key behavior, the towns kids were scared of them as kid-eating monsters.

With strong sunlight on my back, I see a figure that responded to my cry for help and it was one of the kid-eating monsters in rags. Reflection of sunlight from the river makes it hard to keep my eyes open or maybe I just don’t want to. The world is too bright to be seen because of the sunlight reflection or his shining eyes of fear and sorrow. The world is just too bright…

After seeing all going bright and white I woke up to find myself lying in the bush. I had in my hand a pretty blue pebble one of the kids had bragged about all the time and how he thinks silly he was to throw it at the monsters one day. I still remember the sky I saw lying in the bush was warm and bright, and the sunlight was a little ticklish.

Add Comment