May 29 is a festive holiday in Turkey. That is when people—most of them, I should say—celebrate the conquest of Constantinople in 1453 by the forces of Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II, also known as Fetih or “the Conqueror”; that day culminated a long siege in which thousands of people died. There are reenactments, fireworks, parties and  chest-thumping speeches in the plaza outside Hagia Sophia, the splendid and historic church-cum-mosque that now serves as a museum. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, an ardent Mohammedan and Turkish nationalist, plays his role to the hilt. Most recently, he came from Ankara to Istanbul (renamed by Kemal Ataturk in 1930) and spoke before a massive gathering. Erdogan praised the Sultan and his soldiers, saying they had changed the course of world history. The fall of this once-impregnable Christian city, capital of the Greek-speaking Byzantine Empire for more than 1,100 years, was a significant event. He was right about that. But a celebration? I would suggest that bitter regret is more appropriate.

chest-thumping speeches in the plaza outside Hagia Sophia, the splendid and historic church-cum-mosque that now serves as a museum. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, an ardent Mohammedan and Turkish nationalist, plays his role to the hilt. Most recently, he came from Ankara to Istanbul (renamed by Kemal Ataturk in 1930) and spoke before a massive gathering. Erdogan praised the Sultan and his soldiers, saying they had changed the course of world history. The fall of this once-impregnable Christian city, capital of the Greek-speaking Byzantine Empire for more than 1,100 years, was a significant event. He was right about that. But a celebration? I would suggest that bitter regret is more appropriate.

Constantinople, formerly the “Queen City of Christendom,” sits on the west side of the Bosporus—a 31-kilometer strait that serves as the boundary between Europe and Asia. In such a crucial position, it was valued politically, militarily and economically. The Ottomans, who had encircled Constantinople since winning the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, considered the city rightfully theirs. It was “a bone in the throat of Allah.” The defending Byzantines had seen Constantinople shrink to just 50,000 souls and were now accustomed to paying tribute. Their weakness can be explained in part by the damage done in the fourth Crusade (1202−1204). Pope Innocent III had called for the  liberation of Muslim-controlled Jerusalem. That did not happen—would that it had! Instead, Christian armies were sidetracked. They stopped at Constantinople, got involved in an internecine squabble, took control and did not leave until 1261. The Ottomans saw the city as an obvious target, laid siege in 1422 and nearly prevailed. The natives shouted hymns to the most holy virgin, thankful that she had saved the day. Maybe she had, but it was a temporary respite.

liberation of Muslim-controlled Jerusalem. That did not happen—would that it had! Instead, Christian armies were sidetracked. They stopped at Constantinople, got involved in an internecine squabble, took control and did not leave until 1261. The Ottomans saw the city as an obvious target, laid siege in 1422 and nearly prevailed. The natives shouted hymns to the most holy virgin, thankful that she had saved the day. Maybe she had, but it was a temporary respite.

The emperor and patriarchs of Orthodox Christianity knew the infidels would be back, so a high-level delegation traveled to Florence and Rome. With no less than survival at stake, they were willing to concede papal supremacy and other theological points. Three decades later, Mehmed II and his army of 80,000 came a-calling, and they did not bring flowers. (It is interesting to note that quite a few of them were not Turks but young men from Christian families in southern and southeastern Europe who had been conscripted as Janissaries under the infamous devisirme system; girls were sent to the harem. All, male and female, were forced to convert.)

Despite the need for urgent and large-scale help, they did not get it. At least one man, however—Giovanni Giustiniani Longo—was willing to act. This charismatic Genoese captain gathered 700 professional soldiers on the island of Chios and took them to the defense of Constantinople. Upon their arrival, Emperor Constantine XI put him in charge. Longo repaired the old Theodosian walls, kept the various factions from fighting among themselves and almost succeeded in holding off the horde of invaders.

Chios and took them to the defense of Constantinople. Upon their arrival, Emperor Constantine XI put him in charge. Longo repaired the old Theodosian walls, kept the various factions from fighting among themselves and almost succeeded in holding off the horde of invaders.

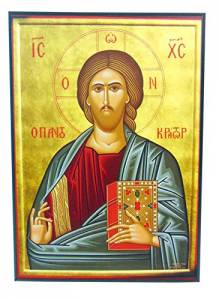

Longo’s cause was not helped by a huge cannon, the handiwork of a Christian apostate named Urban. This thing, hauled by 60 oxen from Adrianople over a three-week span, proved effective in pulverizing the walls. Eventually, the dreaded happened as they were breached. The Turks poured in through the Kerkoporta Gate. They met some resistance, but with Longo injured the Constantinopolitans were soon in full retreat. There was indiscriminate slaughter, rapine and enslavement. Monks, nuns, lay people, children and the elderly were all at the mercy of Mehmed II’s men, and mercy was in short supply. They roared along the main street, known as the Mese, burning, looting and killing whosoever they pleased. Upon reaching Hagia Sophia, the old and sacred cathedral, they did not hesitate to bust down the massive doors. You can be sure the faithful huddled inside were praying as never before, calling on Theotokos (Mother Mary) for a miracle. Bells tolled, incense burned and icons were paraded all around the church. It was to no avail, though. Mehmed II pranced up on a horse—a scene of great reverence for subsequent  generations of Turkish schoolchildren—and told his imam to recite the Shahadah: “There is no god but Allah, and Muhammad is his messenger.” The Sultan’s soldiers desecrated Hagia Sophia’s altar (soon re-oriented to face Mecca), and the church became a mosque. The cross atop the dome was removed, and four large minarets were erected at the corners.

generations of Turkish schoolchildren—and told his imam to recite the Shahadah: “There is no god but Allah, and Muhammad is his messenger.” The Sultan’s soldiers desecrated Hagia Sophia’s altar (soon re-oriented to face Mecca), and the church became a mosque. The cross atop the dome was removed, and four large minarets were erected at the corners.

Mehmed II, who ruled until his death 28 years later, repopulated the city with tens of thousands of Mohammedan Turks from Anatolia, and even invited some of the surviving Greeks to stay—as long as they were willing to submit to dhimmitude status. The loss of Constantinople was a terrible shock to Christendom, a nightmare for Orthodox and Catholics alike. They talked about somehow re-taking the city in the decades to come, but that was mere fantasy. I suppose I can take a measure of comfort from the Spaniards kicking every last stinking Moor out of the Iberian Peninsula in 1492, and victory in the Battles of Lepanto (1571) and Vienna (1683), but I surely do not celebrate on May 29; Erdogan and I part ways on this matter. According to Biblical scholars, Psalm 79 can be interpreted as referring to the loss of Constantinople. Here are its first three verses:

O God, the heathens have invaded your inheritance;

they have defiled your holy temple,

they have reduced Jerusalem to rubble.

They have left the dead bodies of your servants

as food for the birds of the sky,

the flesh of your own people for the animals of the wild.

They have poured out blood like water

all around Jerusalem,

and there is no one to bury the dead.

3 Comments

This explanation is very informative. Retaliation from the Crusades is painful to accept but holy wars weren’t so holy. It was and still is the epitome of hate.

I found it interesting that some considered the fall of Constantinople to be the beginning of the Renaissance, since the intellectual break from the church and thus free thinking was attributed mostly to Martin Luther when he nailed his thesis on the door of the Wittenberg church.

Either notion starts with the same premise, no more blind obsequiousness to illiteracy and servitude to a corrupt church.

One thing I couldn’t find a place to use is as follows. As soon as the Turks roared in and took over, they started fighting among themselves about who would get to enslave the most beautiful young women. In some instances, these guys fought to the death….

The last Roman Emperor, Constantine XI Dragases Palaiologos fought heroically and died like a real Roman Emperor!!! He denied abandoning his beloved Constantinople although Mehmet gave him this option, while he knew he was going to die. He asked from his soldiers to leave Constantinople if they wanted, but only a few left him. The majority prefered to stay and fight on his side even when they understood that the City will fall and this shows his great personality. Btw, Excellent article, Richard.

Add Comment